Going over some of the catalogue records in our general collections in preparation for the switch to a different library platform is an experience not entirely unlike walking through the stacks. While I can’t see the volumes themselves, going through the catalogue by call number, rather than title or subject as we are wont to do, offers a rough equivalent to the shelves beneath the Fisher’s reading room. Record by record, rather than volume by volume, the breadth of the Fisher's collections is still impressed on my mind. This task has also introduced me to volumes that I would otherwise have had no idea existed, and has once or twice lead me down exciting and interesting research rabbit holes.

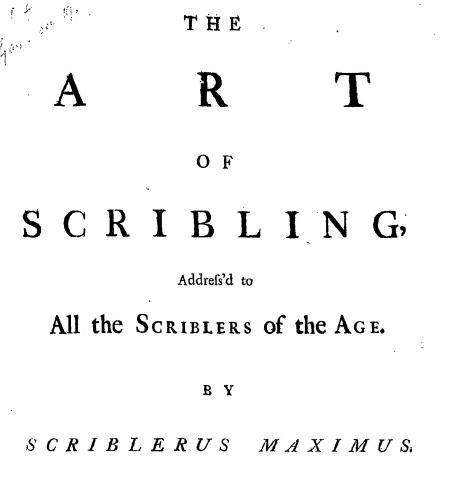

One such case is "The Art Scribbling" by “Scribus Maximus” (a pseudonym, or else a very fortuitous coincidence on the part of the author...), a satirical poem published as a pamphlet for A. Dodd in 1733. It was listed in the October 1733 issue of The London Magazine, and Monthly Chronologer, under “Poems, Plays, and Entertainment” for 1 shilling, then was published in November. The presented rhetorical context of this poem is one writer giving advice to other aspiring authors "by which to live, and earn an honest Penny" (3). Through the guise of such 'helpful' advice, the author pokes fun at numerous aspects of the contemporary textual market, from the tendency of newspapers to publish false or overly dramatized stories — “Should you be told/ some Man of Note is ill,/ Though Death may linger, you at once may kill:/ If he recovers, you was but mista’en,/ And may with ease return his Life again” (9) — to the public’s habit of buying books based purely on the title. The author further mocks English literature for being ridiculous and enabling the public’s degeneration. He particularly derides dramatic works: "Farces are now a most increasing Trade/ For nought in Nature is so easy made… Your Business is half done when you have got,/ A Dramatis Personae, and a Plot" (11). The last pages are dedicated to mocking Edmund Curll (1675-1747), specifically for his tendency to print pirated works with falsified authorizations on their title pages. The “Scriblerus Club” to which this poet’s pseudonym alludes was formed by some of the premier poets of the time in response to what they deemed was a banal and tasteless literary moment, and Edmund Curll was a particular target of this group: in the 1710s-20s, Alexander Pope, Nicholas Rowe, and Jonathan Swift quarreled with him over his publications.

The Fisher’s copy of "The Art Scribling" is bound together (or "bound with," as we cataloguers call it) with forty-odd other pamphlets from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, most of which are in some way connected to the Scriblerus Club. Many of them are satire or satirical poetry commenting on the contemporary political moment; names such as Alexander Pope and poet-politician Isaac Hawkins Browne appear multiple times. The choice to bind together these pamphlets together offers a fascinating lens by which to see how a past collector processed this textual moment. These pamphlets’ publication dates span 50 years and vary in genre and language, but together they offer an illuminating slice of the literary-satirical moment in early 18th century London. Such bindings are a powerful agent against isolationist tendencies or ahistorist scholarship, prompting comparisons or connections that may not have been possible otherwise.

Luckily for my curiosity, a copy of “The art of scribling” is available on Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). Such collections are a testament to the many ways humanities scholarship has taken full advantage of technological advancements and made pre-industrial material more widely available. Studying a text housed at a library in Toronto, while sitting at my parents' dining room table in Kansas, via a digitization provided by Harvard (ECCO hosts a reconstruction of the Houghton’s copy), is a feat that would have been unimaginable a few decades prior. Moreover, it is less likely I would have noticed this volume if I had just been walking by — forty-odd catalogue records with the same call number stands out far more than a text resting quietly among other like-sized volumes. With catalogue records, in many ways the content of the book becomes the point of its recognition, rather than its material instantiation.

However, this is not to suggest that the ECCO copy was an equitable trade-off. There are many things about this text that would become more clear if I had access to the physical volume: whether the pamphlets were cut down to the same size when they were bound together, for example, or whether there is any marginalia accompanying this work. Many allusions to contemporaneous authors are censored in the print version of this work — have they been filled in in the Fisher’s copy? The numerous benefits of working with the material directly are most keenly felt when it’s necessary to stay away. I am eager for the future opportunity to spend some time with this text in person.

- Megan E. Fox, Graduate Assistant, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

References:

Baines, Paul and Pat Rogers. “Trading Blows (1714–1716)” in Edmund Curll, bookseller. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Marshall, Ashley. “The Myth of Scriblerus.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies Vol. 31, 1 (2008): 77-99.

Scriblerus Maximus. The art of scribling, address'd to all the scriblers of the age. London, MDCCXXXIII. [1733]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale. University of Toronto Libraries. 15 May 2020.