Between 2016 and 2018, three new archival collections came across my desk that had one thing in common – the creators, nineteenth-century upper-class British men, had all been in the Royal Navy and all three were talented watercolourists. Before I became a librarian, I studied art history, and I was intrigued by this connection between the Navy and art. I turned to our library catalogue to see what our collections could teach me about watercolour. This exercise led me to explore archival collections, manuscripts and books and took me on an exciting journey from the Canadian Arctic aboard the HMS Terror to Milan with the famed artist and critic, John Ruskin.

The material below, which represents just a fraction of the original watercolour art held by the Fisher, was first displayed as a monthly highlight exhibition in May 2019.

In 1782, William Gilpin, an English schoolmaster, published Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, etc. relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the summer of the year 1770. This book focused on the topic of picturesque beauty, “that of not merely describing; but of adapting the description of natural scenery to the principles of artificial landscape; and of opening the sources of those pleasures, which are derived from the comparison.” Published alongside these writings were reproductions of the author’s watercolour sketches. Gilpin’s books became immensely popular, and in turn popularized watercolour as an ideal medium for landscapes and nature. Gilpin’s promotion of watercolour to capture the picturesque corresponded with the first commercial sales of cakes of soluble watercolour and prepared paper in 1780. These innovations reinvented watercolour from a time-consuming and expensive endeavor to an easy portable medium available to both the amateur and professional artist.

The commercial availability of watercolour allowed the medium to grow in popularity among British landscape artists, such as J.M.W Turner (1775-1851), John Constable (1776-1837) and John Ruskin (1819-1900). The art was further promoted by the establishment of the Society of Painters in Water Colour in 1804. At this same time, Britain’s expanded colonial empire meant that global travel became more widespread. Travel, whether it be for pleasure or work, became an available reality for the British upper classes and packed along in their cases were sketchbooks, brushes and watercolours to depict their journeys and experiences.

Attributed to John Ruskin. Milan Cathedral. [18--]. Watercolour on paper. MS Coll. 167, box 24.

Forty years before Gilpin, cadets at the Royal Naval Academy were trained in watercolour drawing and surveying, particularly of harbours and coastlines. The growing popularity of the medium led to the expansion of watercolour instruction at Naval Academies to all cadets by the beginning of the 19th century. Accordingly, painting in easily transportable sketchbooks became a popular pastime for men at sea such as Captain Owen Stanley (1811-1851) aboard the HMS Terror in the Canadian Arctic in 1836, Captain Benjamin Branfill (1828-1899) in India in 1875 and Captain Fritz Crowe (1849-1904) off the coast of Africa and Brazil in 1882. In contrast with Gilpin, watercolours done by the Navy had their basis in the traditional format of marine painting rather than searching for the picturesque. Therefore, men in the navy were taught that painting should be made to ‘inform rather than to please.’

Benjamin Branfill. Tomb on the Side of Road to Station. 1875-1876. Watercolour on paper. MS Coll. 746, box 9.

Fritz Hauch Eden Crowe. Watercolours of Africa and Brazil. 1879-1882. Watercolour on paper. MS Coll. 751, box 1, folder 2.

Watercolour was deemed a suitable pastime for young upper-class and aristocratic women. The guide, The Young Ladies Instructor in Ornamental Painting and Drawing, encouraged young women to make watercolour paintings to be sold for charity at “fancy sales, presents to your friends, or decorating your own rooms.” Emily Mary Bibbens Warren’s (1869-1956) watercolour, made when the artist was eight years old, included herself, her four sisters and her mother engaged in their painting and surrounded by their already finished work. Emily Warren, the last student of John Ruskin having written to him as a precocious ten-year-old would go on to become a professional artist. She moved to Canada and traveled widely throughout the country including giving lectures with original glass slides of her works.

Emily Warren. [A Family of Artists]. c. 1876. Watercolour on paper. MS Coll. 167, box 24.

Watercolour as a hobby stretched over the gender divide, and instructional books and treatises on watercolour painting, for both men and women, were published in increasing numbers in the early nineteenth century. These books included both an education on the commercial available colours, brushes and paper, as well as tips on painting, such as for outlining mountain ranges, atmospheric effects and the best place to sit when working from nature.

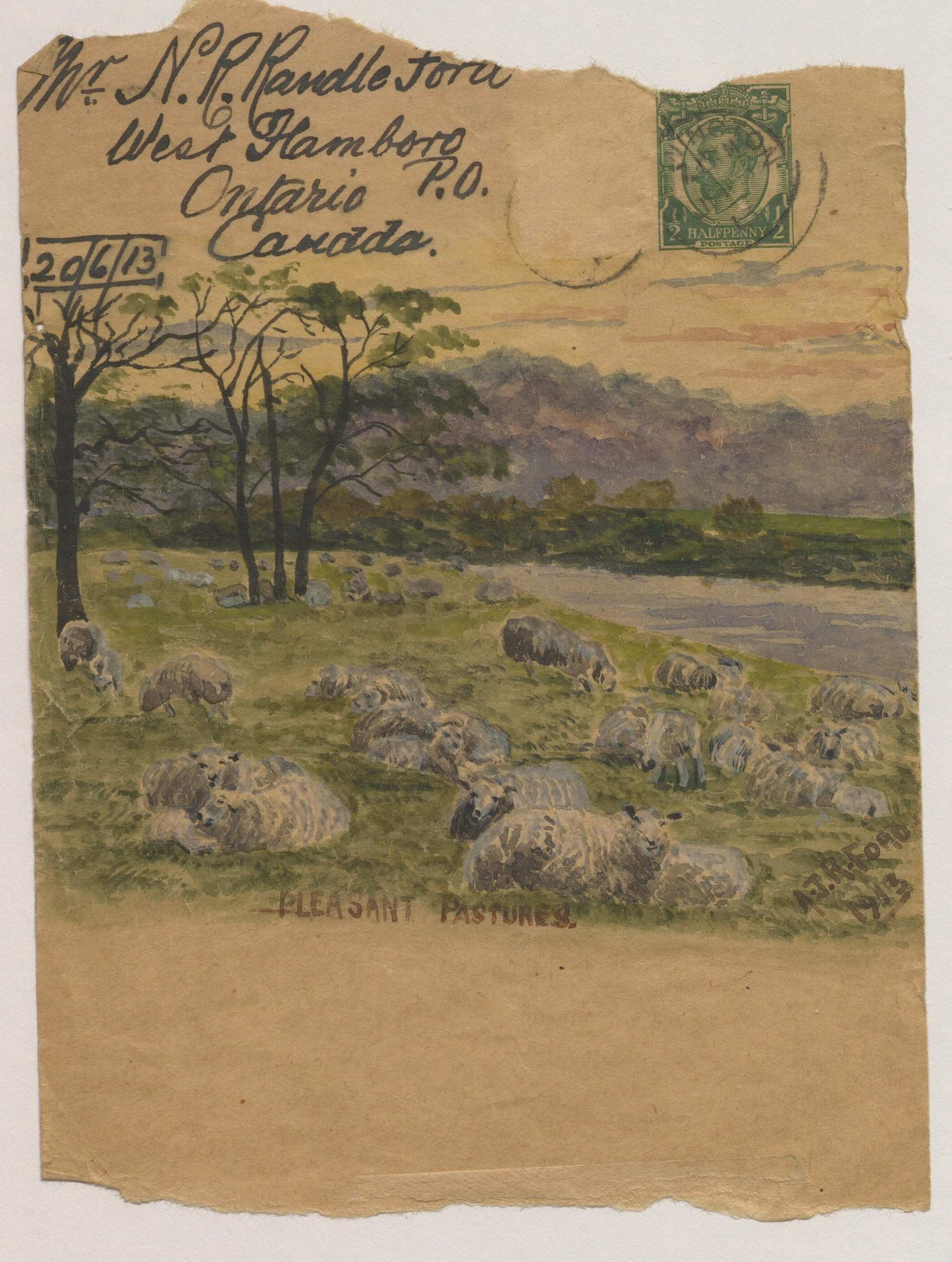

By the end of the 19th century, photography had superseded watercolour as the most convenient way to document one’s travel. While photography was an easier way to reproduce scenes, its format did not allow for the subtle or creative alterations encouraged by those painting the picturesque, nor did it allow for the intricacies of the colours found in nature. The result was a continuation of paintings for travel as well as those of a sentimental nature. An unknown, and very talented, painter created a two-page panorama of the mouth of the Humber River in Toronto during his travels through Ontario, Quebec and California around 1880. Similarly, Lauchlan Alexander Hamilton (1852-1941), a Canadian Pacific Railway surveyor, who is credited with the layout of streets of Vancouver, moved away from his utilitarian profession during a trip to England, to paint the rural scenes of Kent. Arthur John Randle Ford (1852-1922), who first learned how to paint watercolours in the Navy, wrote weekly to his son, who had immigrated to Canada in the early twentieth century. To each letter he added an original watercolour painted on the envelope. These envelopes depicted the nostalgic quality of childhood and reminded his far-away son of familiar places and the unique landscapes of rural England.

Artist Unknown. Mouth of the Humber. 1880. Watercolour on paper. MSS 01128.

Lauchlan Alexander Hamilton. Looking Towards Northern House. [188-]. Watercolour on paper. MSS 01264.

Arthur John Randle Ford. Watercolours on envelopes sent to Canada. 1913. Watercolour on paper. MSS Gen. 60.

- Danielle Van Wagner, Special Collections Librarian