By the time Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) wrote Le livre de paix (The Book of Peace), a manuscript of which the Fisher recently acquired (MSS 05041), she was approaching the end of her career as an author. She would live to see, and write about, French defeat at Agincourt and French victory at Orleans but Le livre de paix, begun in 1412 and completed in 1414, is often accounted her last major work. The third in a loose trilogy of political works in the mirror-for-princes tradition, Le livre de paix is addressed to the Dauphin, or Crown Prince of France, Louis de Guyenne (1397–1415), and sets out Christine’s vision of an ideal ruler.

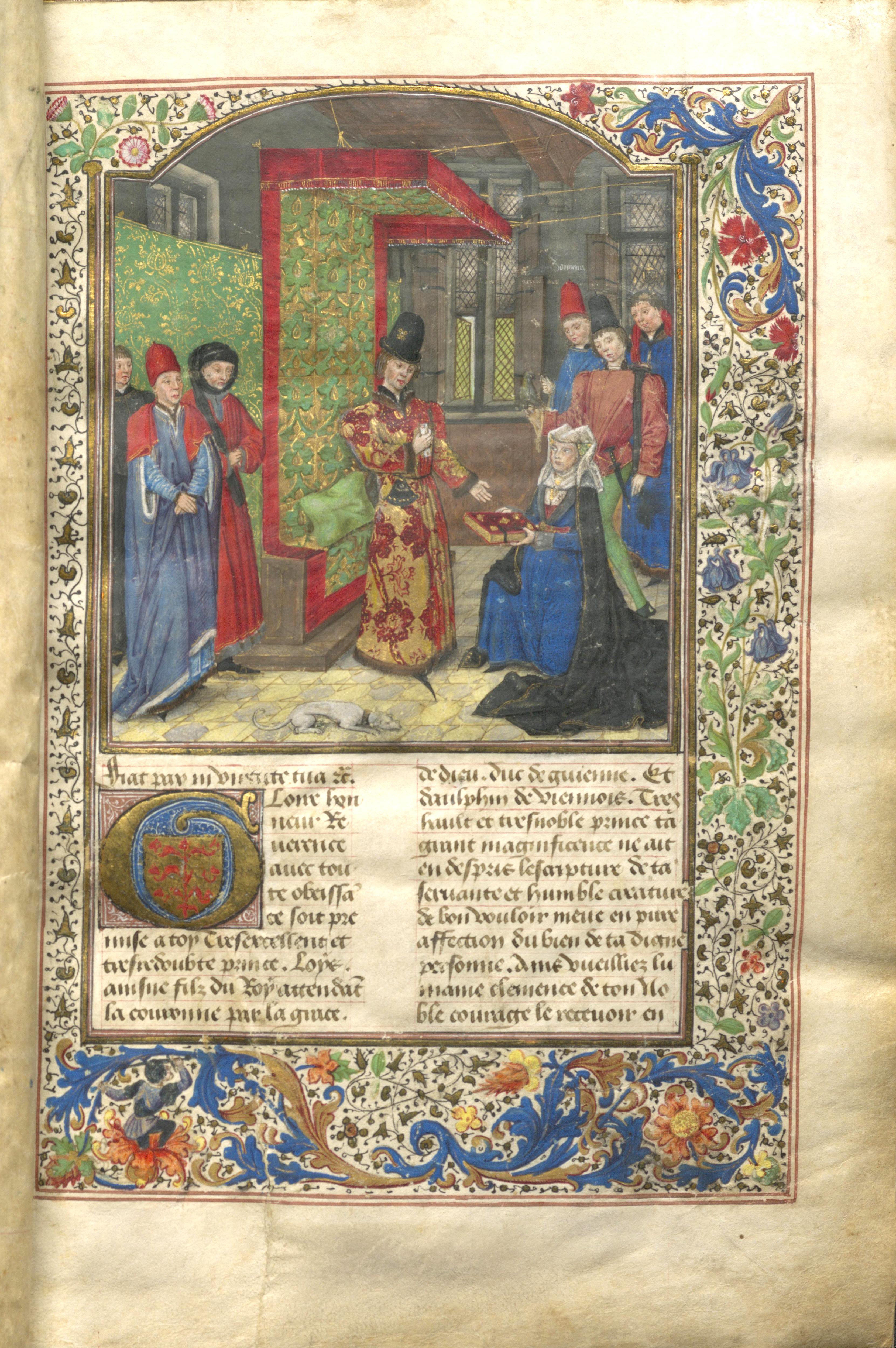

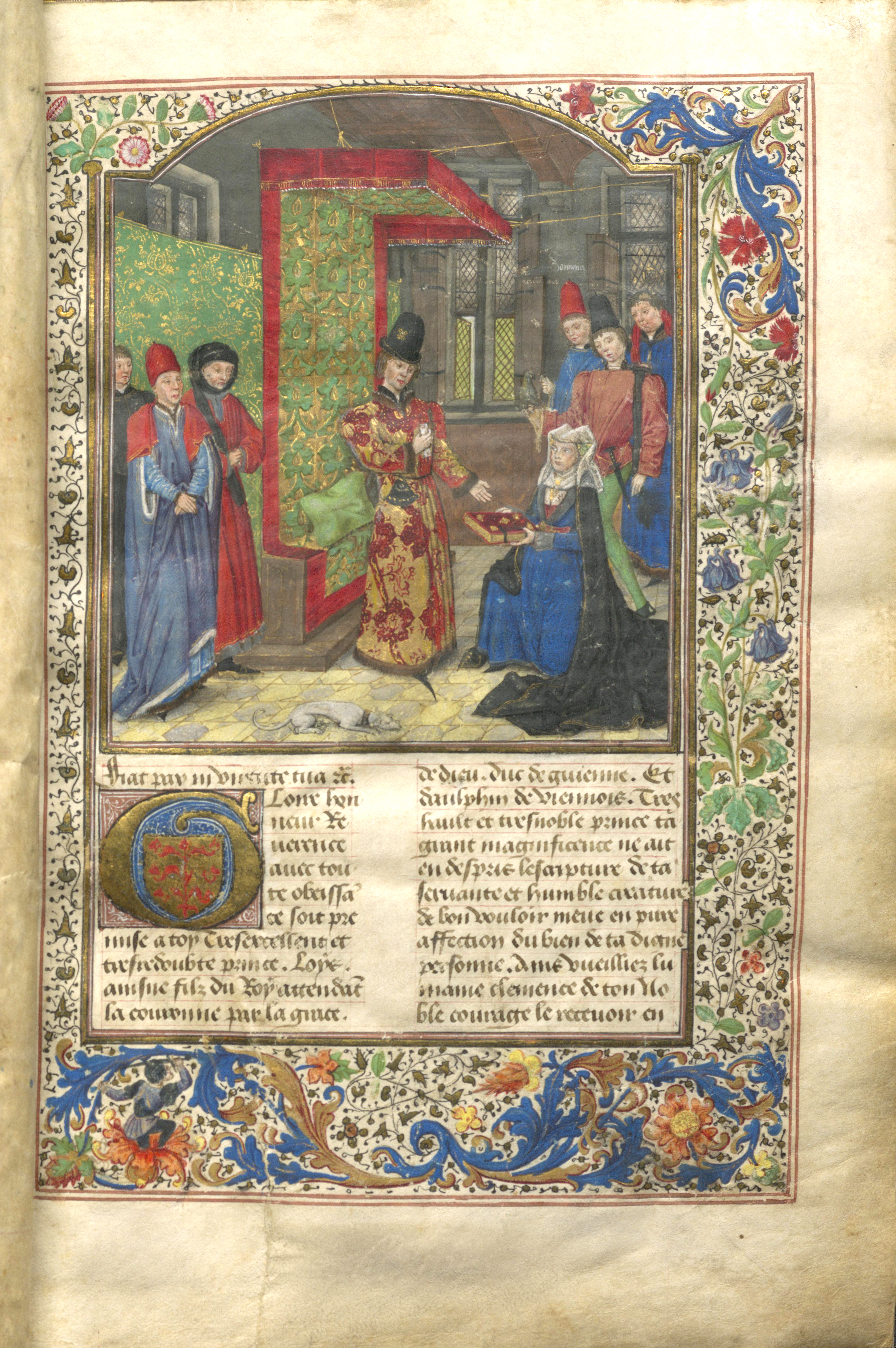

The Fisher’s copy of Le livre de paix features a miniature by the Flemish artist Jean Hennecart (fl. 1454–1475) in which Christine presents a copy of her work to Louis. Christine is shown dutifully kneeling before the Dauphin, but whether any real respect attends her duty is less certain, and the sidelong look she fixes on him instead suggests suspicion. In this the artist has perhaps captured, whether intentionally or not, Christine’s true opinion, for although she begins Le livre de paix by praising Louis’s political accomplishments, and in particular his role in securing peace between France’s two rival factions, the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, she also feels the need to insert into her work warnings against ‘addiction to shameful pursuits’ (II.14). (We learn from other sources that Louis had spent the early part of 1413 working hard to gain a reputation for debauchery. Nor has subsequent literature done anything to rehabilitate his reputation – he is the inept Dauphin of Shakespeare’s Henry V.) In short, we find Christine in confident mood in Le livre de paix, happy to offer both advice and (at least implied) censure to a prince.

This was, however, a confidence that Christine had had to earn, and her first literary efforts give a very different impression. The second half of the 14th century, like our own times, was familiar with pandemic and all its consequences. The Black Death reached France in 1348 and returned with unnerving unpredictability for the following three centuries. Christine herself was directly affected. In 1379, at around 15 years of age, she married Etienne du Castel, a royal secretary. In 1389, however, Etienne died of the plague, leaving Christine to provide for her mother and three children. Confronted with legal difficulties when trying to claim her inheritance, by the early 1390s Christine had turned to writing poetry to support herself and her family. Many of her ballades from this period, by the skilful deployment of which she was able to win noble, and ultimately royal, patronage, describe in unflinching terms the effects of her husband’s death. Here are two such poems, two of her most famous, from Cent balades (One Hundred Ballades), her earliest collection. In the first she expresses the range of her emotional response, from grief, to anger, to despair; in the second she narrows her focus to the theme of isolation, one familiar to many today:

VI. Dueil engoisseux, rage desmesurée

A choking grief, and pain beyond all measure,

Despairing sadness, sadness filled with anger,

Dejection without end, a piteous life

Tormented by despair and filled with weeping,

A heart in pain that hides itself in shadow,

A darkening body at the edge of death,

An unremitting, constant cry of grief,

And I can not be cured, nor can I die.

A brutal, cruel existence that admits

No joy, but brings sad thoughts and deepening groans,

Boundless distress, locked in a worn out heart,

A bitter anger, carried secretly,

A sullen manner, drained of any pleasure,

And painful hope, which blights all that it touches—

All these are mine, and not one ever leaves me,

And I can not be cured, nor can I die.

And every day some sad preoccupation,

With cruel wakefulness, or troubled sleep,

And all exertion is in vain, but brings—

Its sole effect—a sad and careworn face,

For all the ills that one can dare imagine—

Painful afflictions, past all hope of healing—

They all torment me unrelentingly,

And I can not be cured, nor can I die.

My princes, pray to God that he may grant

Me death, unless he wishes to devise

Some other means to cure my cruel despair—

But I can not be cured, nor can I die.

XI. Seulete suy et seulete vueil estre

I am alone, I want to be alone,

I am alone, and my sweet love has left me,

I am alone, without a friend or master,

I am alone, in sorrow and in anger,

I am alone, dejected, ill at ease,

I am alone, no woman more afflicted,

I am alone, and left without my love.

I am alone, whether at door or window,

I am alone, and hidden in a corner,

I am alone, and feed myself on weeping,

I am alone, whether distressed or calm,

I am alone, nothing so ill becomes me,

I am alone, confined within my chamber,

I am alone, and left without my love.

I am alone, in my entire being,

I am alone, whether I sit or walk,

I am alone, no other mortal more so,

I am alone, and everyone has left me,

I am alone, and cruelly diminished,

I am alone, and often wet with tears,

I am alone, and left without my love.

My noble lords, my pain has now begun,

I am alone, threatened by every grief,

I am alone, darker then any mulberry,

I am alone, and left without my love.

Christine’s career began, then, as a response to crisis, propelled by a combination of necessity and grief, and ended with her admonishing the Crown Prince of France. But how did she get from such a beginning to such an end? An answer, or at least part of one, can be found in the title and contents of a work written by Christine in 1402-1403: Le livre du chemin de lonc estude (The Book of the Path of Long Study). At the beginning of this long poem she describes the death of her husband and her response to it, though now after the lapse of a number of years. Still beset by grief and living an isolated life, she turns one day to reading. The first few books she tries are of little help, but:

At last there came into my hands a book

That filled me with delight and lifted me

Out of dismay and hopelessness: Boece,

The Consolation of Philosophy

(A very famous, useful book); and as

I read, my anger and my sadness passed

Away…

(202–211)

It is in reading, then, that Christine first finds relief from her suffering. And nor should we imagine that her reading ended with Boethius, for in the rest of the poem she unfolds an elaborate dream-vision that in its incorporation of geography, astronomy, politics, and literature – most notably Dante – bears witness to what must indeed have been 'long study'. Such learning is on display in many of Christine’s works; we find it embedded in the very structure of Le livre de paix, each section of which begins with one or more quotations from a wide variety of authors.

Reading, it must be admitted, is a privileged response to disaster, and Christine herself only describes coming to it more than a decade after her husband’s death; at the actual moment of crisis we, like Christine, are often faced with more immediate concerns. (Though equally, the current pandemic and attendant lockdown are for many people a slow crisis, one that leaves many hours to fill.) But whether or not we have time for them – or even access to them – in our present circumstances, it is at least some consolation to know that books, including all those locked up in the Fisher, will be waiting for us once the crisis has passed.

Timothy Perry, Medieval Manuscript and Early Book Librarian