How do you read a book that has no words?

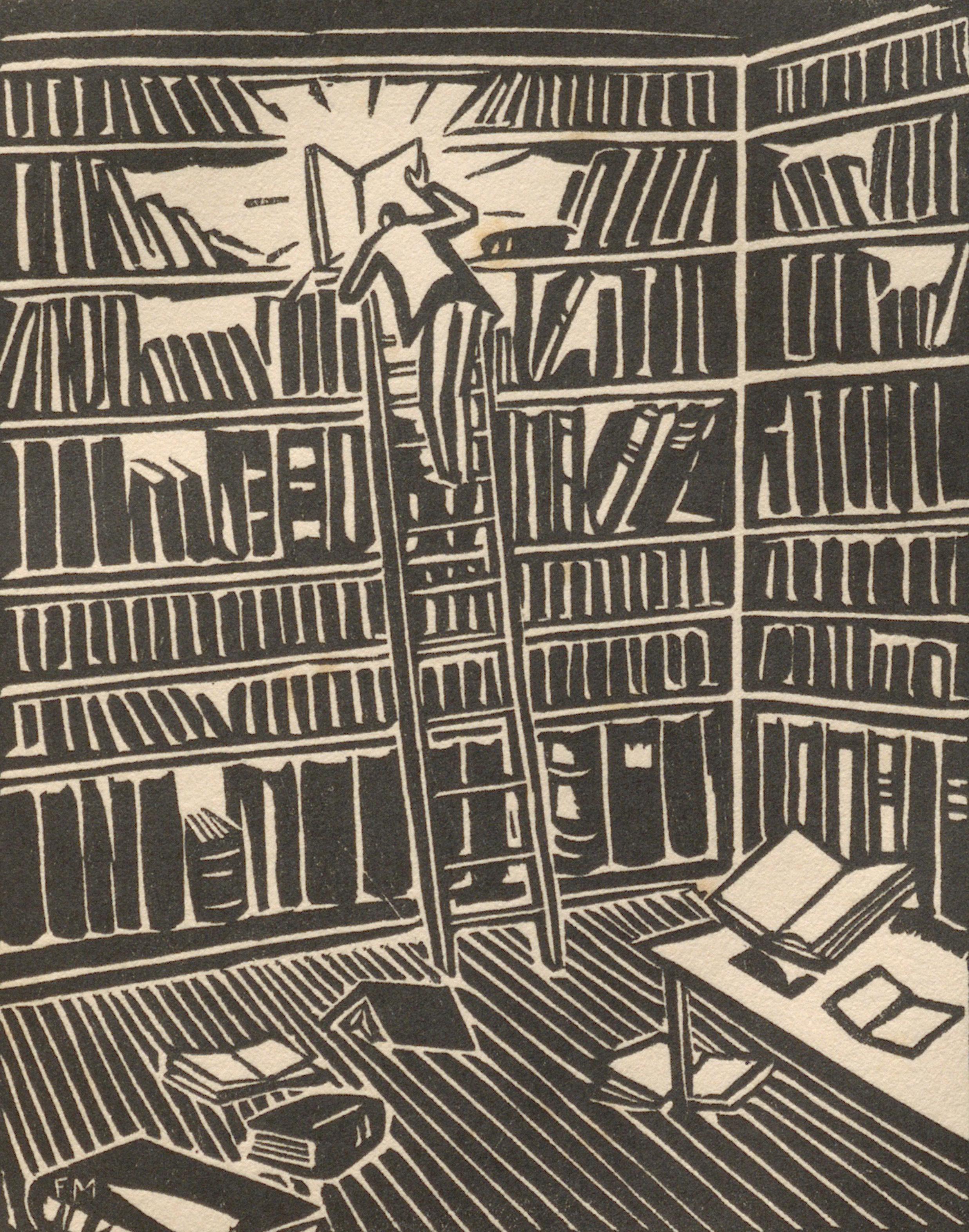

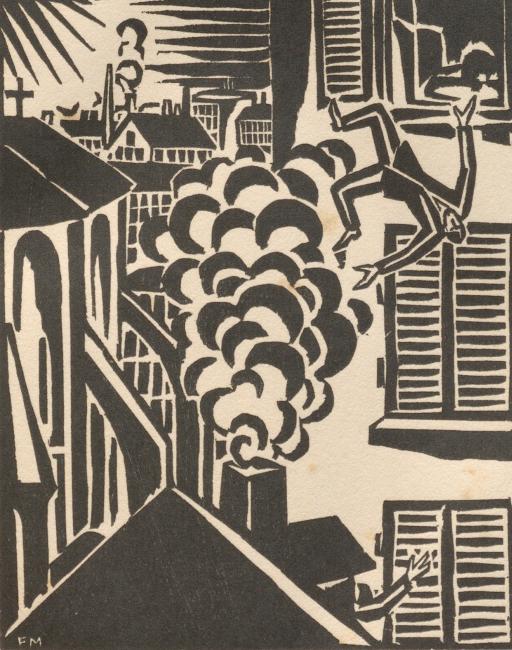

In 1919, Frans Masereel (1889-1972) invented a new type of book: romans in beeiden, or novels in pictures. His first novel, Mon Livre d’Heures or Mein Stundenbuch (My Book of Hours), was published in 1919, first in Switzerland and soon after in Germany. It featured 167 original woodcut prints and not a single word. Within two years, he would publish three additional books. Masereel’s four wordless novels reflect the fascinations, and literary and pictorial leanings, of Europe immediately after the First World War. As books they stand as a succesor to the earliest form of book printing, and a precursor to comic narrative structure and the modern graphic novel.

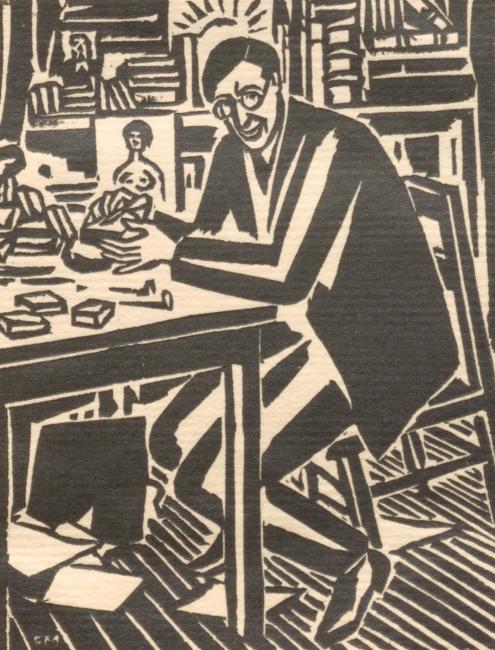

Frans Masereel led a life that intersected yet never fully associated with any of the major artistic movements. Born on 31 July 1889 in the Flemish town of Blankenberge, near Ghent, he spent much of his adult and professional life in Paris. He settled in Paris in 1908 and was surrounded by the avant-garde movements of Fauvism and Expressionism, but he was artistically independent, and preferred to look back through history than be influenced by contemporary artistic trends. It was the years he spent away from Paris that had the most influence on his artistic style and the creation of his wordless novels. He left first for pastoral Brittany in north-west France. It is there, in 1913, where he created his earliest-known woodcut, in the style of Pieter Bruegel (1525-1569), but he would only truly dedicate himself to this medium in earnest after the onset of the First World War.

An ardent pacifist, he made his way to Switzerland in 1916, where worked as a translator for the International Red Cross. In Geneva, he joined a social and intellectual group of other pacifist artists and writers, most notably, Romain Rolland (1866-1944), who had been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature the year before, and who would later write the preface to Masereel’s first American edition. In 1916, in association with French typographer Claude Le Maguet (1887-1979), Masereel co-founded Les Tablettes (1916-1919), a monthly periodical focused on the international pacifist cause. It is in these pages, where Masereel would publish his first modernist woodcuts, with the human figure distorted by the horrors of war. During this period, Masereel also worked as an illustrator for La Feuille, a daily newspaper, which sharpened his ability to condense entire narratives into one image. In over one thousand issues, Masereel, given only a few hours, would summarize the news of the day into a single cartoon, drawing or woodcut which would appear on the front cover. In 1917, he published Les Morts parlent (The Dead Speak) and Debout les Morts (Arise Ye Dead): wordless collections of seven and ten woodcuts, respectively, on the disastrous human consequences of war. These incredibly rare pamphlets demonstrate Masereel’s growing interest in using woodcuts to examine social issues and stand as significant predecessors to his later novels.

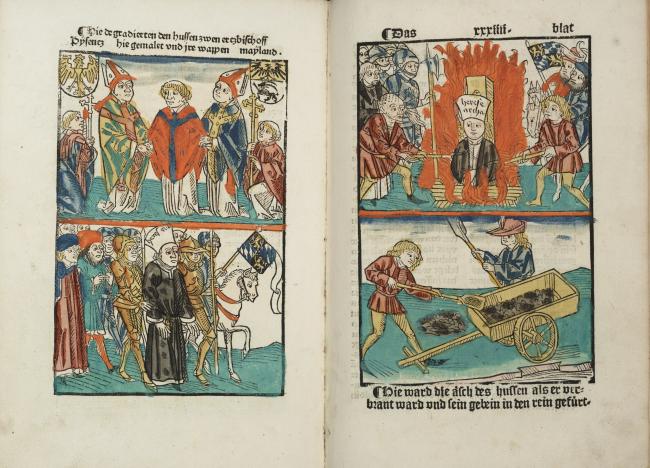

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the medium of woodblock printing experienced a renaissance in style and use. Created by carving a relief image into a piece of wood, the woodcut can then be inked and printed multiple times. Dating back over a thousand years in China and Japan, the woodblock came to prominence in the Western world in Germany in the fifteenth-century, largely due to the invention of the printing press and was used as the earliest form of mass-produced illustrations in printed books, most particularly during 1450 and 1550. (Below is an early example of woodblock printing from the Fisher’s collection, Concilium zu Constencz (1483), depicting the execution of Jan Hus.)

Woodblock printing was soon eclipsed, both as an art form and in book illustration, by engraving and etching, which can be far more detailed and intricate, causing the woodcut to largely fall out of favour between the sixteenth and twentieth century. A surging interest in the woodcut occurred in France during the mid-nineteenth century when artists in the Impressionism and Post-Impressionism movements began collecting woodblock prints from Japan and emulating, most frequently, the style and colours, and occasionally working in the medium itself. The woodcut was further revitalized and adopted by the German Expressionism movement, who saw the medium as an essential part of their Germanic heritage. As early as 1905, Expressionists began to create and print woodcuts, and experimented with using the medium for their modern subject matter. It is uncertain if Masereel was influenced by the periodicals of German Expressisonists, lingering Japonisme in Paris, or if his interests stemmed organically from his fascination with sixteenth-century Flemish artists. Regardless, the resurgence of use and interest in the woodcut in the twentieth-century, particularly in Germany and France, created a ready audience for his extraordinarily popular series of wordless novels.

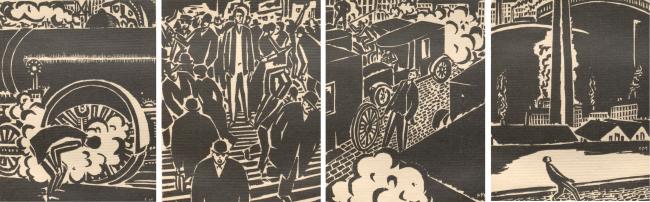

Mon Livre d’Heures follows a young man into the city, where he is introduced to urban modernity, and comes into contact with the tools of industry – both worker and machine. Unlike Masereel’s early anti-war publications, Mon Livre d’Heures focuses on the human condition of the post-war individual, who has witnessed great tragedy and is now plunged into a world filled with new inventions, delights and hardships. Masereel narrates the city, in both its glory and its ugliness, in a way that thoroughly demonstrates modern life that appeals to people of all classes and circumstances.

While subsequent editions would have lengthy prefaces, early editions of Mon Livre d’Heures had no text, except the title, allowing each reader to make their own interpretations, build their own stories and incorporate their own experiences and knowledge into the character and story. The title itself may hint at Masereel’s intentions for how he intended the book to be used and read. He titled his first novel, My Book of Hours, drawing a line back to the medieval religious books of personal devotionals and worship. These books, most commonly in the form of hand-made medieval manuscripts that were occasionally illuminated, allowed wealthy men and women to incorporate a routine of prayer into their daily life. Frequently small enough to be carried on the person, they were intended to be used and ruminated over daily. In his inaugural novel, Masereel reinterprets the religious and upper-class status of the book of hours to address the new modern condition, in which individuals can use the inexact and vague storyline to consider and analyze their own experiences within the modern city. Unlike its medieval namesake, Masereel meant his book for the masses, open to everyone regardless of literacy, class or language.

While Masereel may have hoped for a universal audience for his first novel, he essentially self-published the first edition through his co-owned press Les Éditions du Sablier in Geneva, in a small run of only 200 copies. Within a year, the book was republished in Germany by Kurt Wolff (1887-1963), renowned for being the first publisher of Franz Kafka, and for printing works by German Expressionists. Wolff was such a proponent of Masereel’s work that after an initial first edition of 700 copies printed from the original woodcuts, Wolff proceeded to publish cheap and easily accessible trade editions of Masereel's first and subsequent novels, which created inordinate popularity in Germany. Similarly in the United States, after a first printing of 600 copies, My Book of Hours was republished under the title The Passionate Journey in two subsequent editions of 10,000 and 5,000 copies within two years. Masereel’s books also became popular around the globe, particularly in China, central Europe and the Soviet Union.

Masereel’s first novel was quickly followed by Le Soleil or Die Sonne (The Sun), Idée (Idea) and Histoire sans Paroles (History without Words) in 1920. After creating hundreds of woodcuts for four novels in just over a year, the artist privileged art over narrative in 1921 with his next publications, Un Fait Divers and Visions. Composed of only eight woodcuts each, these works were intended for each image to be considered and contemplated separately rather than as a part of a larger story. In 1922, Masereel moved from Geneva back to Paris, where he continued his career as an artist. While he continued to work with woodcuts for his entire life, he also began to explore engravings and watercolour, and worked extensively as a book illustrator. He would go on to publish additional woodcut novels intermittently until 1968, but these later books would not receive the fame and popularity as his earliest four novels. Throughout the 1920s, he remained exceptionally popular in Germany, partially due to Kurt Wolff, the Expressionists and the Weimar Republic’s fascination with the reinvention of the Germanic woodcut, modernity and urban spaces.

His books were banned by the Nazi party and in 1940, after the German invasion of Paris, Masereel’s studio in Paris was ransacked and his works destroyed as an example of degenerate art. He was forced to flee to Avignon and then again to Laussou in 1943. The Nazi’s declaration of his work as degenerate resulted in his work being associated academically and popularly with German Expressionism up to the present day. However, as an artist and a novelist, Masereel’s style defies definition. Drawing influence from movements, events and people, both historical and modern, his wordless novels emerge as a truly unique form of book and reading. Subsequently, his style, both in the woodcut medium and in his quintessential pictorial approach, has influenced the development of graphic novels and a generation of modern artists, who seek to tell a narrative not with words but with images imbued with emotion and humanity.

The Fisher holds small-run first and early edition copies, printed directly from the original woodblocks, of Mon Livre d’Heures, Die Sonne and Histoire Sans Paroles published in both Switzerland and Germany. These texts have been acquired by the library through generous donation and purchase.

- Danielle Van Wagner, Special Collections Librarian