At the end of this week, April 23, we celebrate World Book and Copyright Day, an annual event organized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization to promote reading, publishing, and copyright. The day itself has meaning: it is the anniversary of the death of both Miguel de Cervantes and William Shakespeare. (Coincidentally, they died on the same day, in 1616.)

To honour the day, we'll be featuring posts all week around the theme of "Books about Books," or books about reading. We begin the series looking at Alberto Manguel's book The Library at Night.

*

For almost a decade I had the privilege of teaching the ‘Rare Books and Manuscripts’ class, which had been introduced to the Faculty of Information curriculum a half century ago by our late director, Richard Landon. Every September I would begin the class by examining the basic concepts of rarity, scarcity, and desirability with regards to antiquarian materials. Ironically, the first time I taught the course, I was experiencing a certain amount of agnosticism with regards to the value of my work. For weeks, I had been cataloguing sixteenth-century Latin theological texts and had encountered a large run of five-hundred-year-old volumes whose pages had never even been cut. Clearly, the books had not been looked at even once from the time they rolled off the presses. Why were we bothering with them? Why was I wasting my time describing the bindings and collating the pages of an item that no one had examined in half a millennium and likely wouldn’t glance at again for another five hundred years? One day, I casually mentioned my skepticism to Richard, and he suggested that I read a book by Alberto Manguel that not only helped me through my own dark night of the book but also revolutionized the way in which I thought, taught about, and approached rare books in general. The book was The Library at Night (2007).

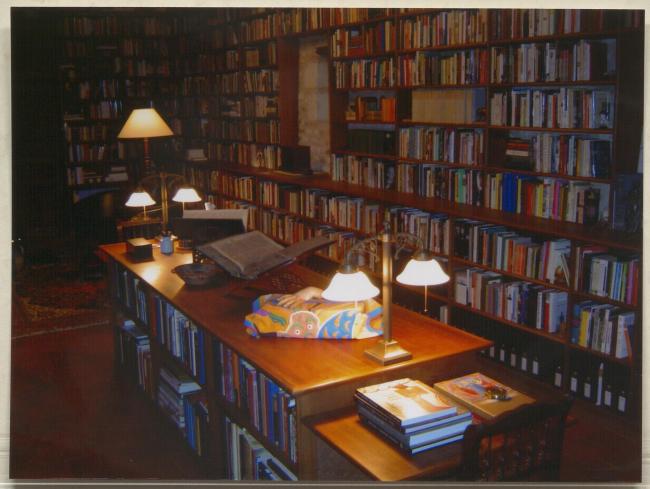

One of Manguel’s principal theses in this volume is that books are accommodating things. As though he were addressing my own private anxieties he wrote, ‘I have no feelings of guilt regarding the books I have not read and perhaps will never read; I know that my books have unlimited patience. They will wait for me till the end of my days.’ (Below is a photo of Manguel's former home library, housed in Poitiers, France.) And beyond, in reality. The information that books contain will be there, waiting for us, whether we open the cover daily, like a prayerbook perhaps, or only when needed, like a cookbook. The frequency of its use may speak to a book’s current popularity or utility, but the information a book contains is timeless; historically conditioned, to be sure, but a last witness to the thought processes of persons living in a certain place and time, and for that reason alone, invaluable and irreplaceable.

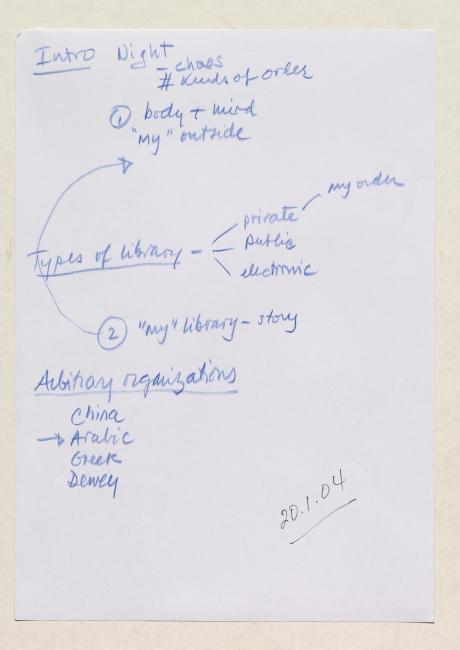

The Fisher Library is privileged to be the repository for all of Alberto Manguel’s papers. It is a truly remarkable collection, reflecting the evolving thought of a novelist and essayist who is a true bibliophile. More than that, however, Manguel’s rich archive, especially the files tracing the writing of The Library at Night from the author’s initial mind map to his final draft, provides a poetic way to appreciate the role that books and libraries play in our lives that the traditionally academic approach simply cannot. Like any good archive, his doesn’t just preserve his thoughts, but reaches out to those who forage within them for new ideas about books. To them he says ‘Readers, censors know, are defined by the books they read’, and that is both a promise and a threat, not readily grasped by those who consider books to be merely passive receptacles of information.

The end of this week, April 23, marks World Book Day. Traditionally, this would be the occasion for the Fisher to display acquisitions made by the library in the previous six months. That cannot happen again now for the second year in a row. It remains as an opportunity for us, however, not only to reflect upon the importance of books in our lives but also, as Manguel reminds us, to reaffirm the crucial role that libraries and librarians play in preserving our literary heritage. 'In my fool hardy youth,' he writes, 'when my friends were dreaming of heroic deeds in the realms of engineering and law, finance and national politics, I dreamt of becoming a librarian.' Being able to share the company of this great man of words in our common quest to preserve cultural heritage is no small honour. It is a privilege to work in a place that safeguards and makes accessible the thoughts of human beings, recorded in manuscripts and books from across the ages. 'Our books will bear witness for or against us,' he writes. 'Our books reflect who we are and who we have been, our books hold the share of pages granted to us from the Book of Life. By the books we call ours we will be judged.'

- P.J. Carefoote, Department Head