Nearly three months into the global COVID-19 crisis, epidemiologists and medical researchers continue to debate when a successful coronavirus vaccine might be developed and to what extent it will help quell the pandemic. Of concern are the several factors that are as yet unknown, including how long the virus incubates, exactly how contagious it is, and, importantly, whether or not being exposed to the virus creates permanent immunity. Oxford researchers recently determined that having the virus once may only offer temporary immunization. If this is indeed the case, then an artificial vaccine might also offer only temporary protection.

The question of immunity recalls some of the earliest experiments with diseases and vaccination, known in its early stages as variolation, the evidence of which can be found in several books in the Fisher Library’s medical collections. Edward Jenner (1749-1823) was an English physician who developed a vaccine for smallpox. While experiments with inoculation were already widespread, the practice was poorly understood and by no means standardized, and it came with serious risks of infection and death.

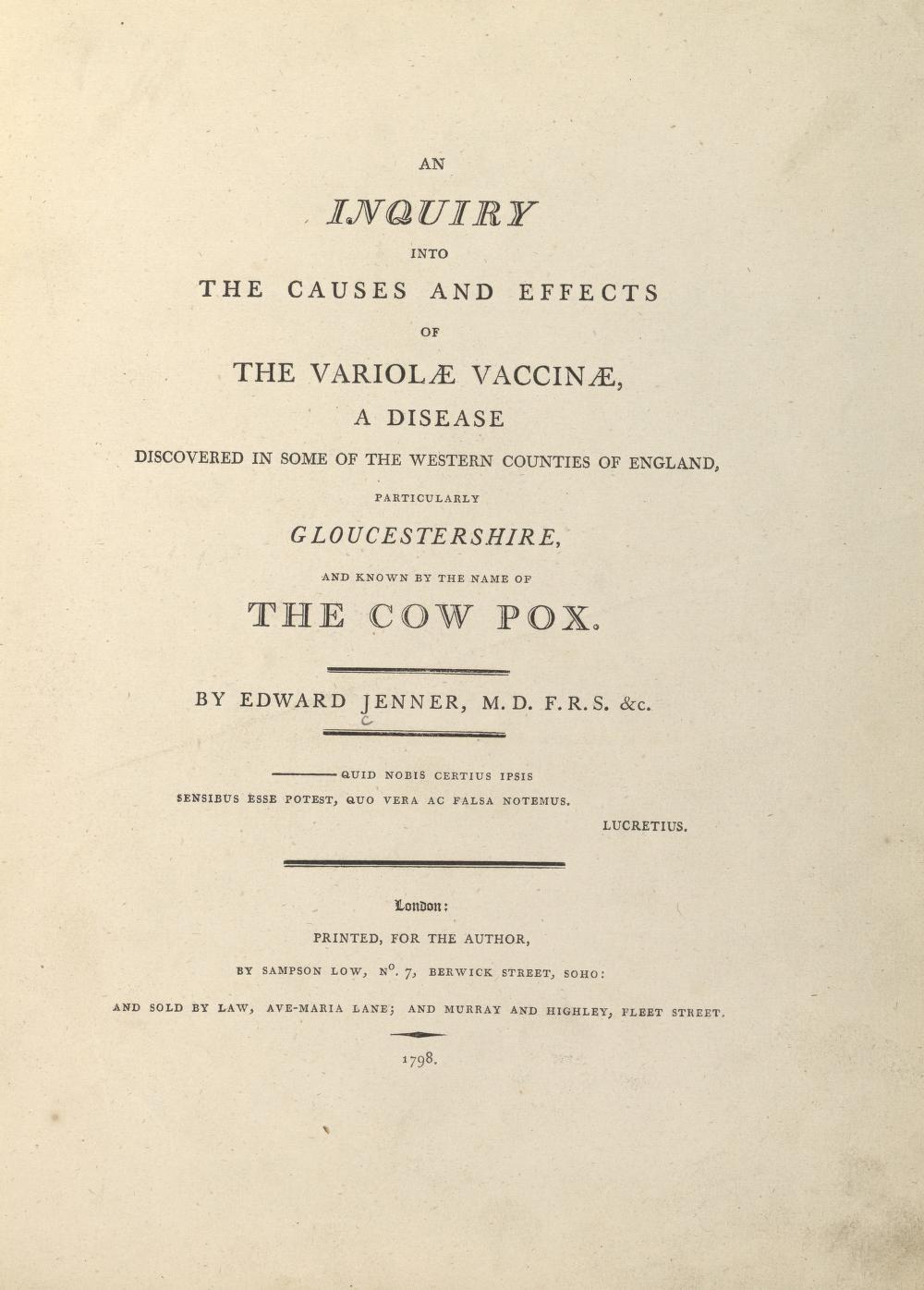

Already aware of the principle of immunity, Jenner observed that dairy farm labourers who were infected with cowpox and were later immune not only to cowpox but also to the much more virulent human version of the virus, smallpox. This prompted him to intentionally infect patients with tissue from cowpox-infected individuals, effectively creating the first successful vaccine. In his Inquiry Into the Variolae Vaccinae Known as the Cow Pox Jenner describes the case of a young boy James Phipps who, after being inoculated with pus from a milkmaid infected with cowpox, was soon after also immune to the smallpox virus. The Fisher Library owns one copy of the first edition of Jenner’s Inquiry, published in 1798, and two copies of the second edition of 1801.

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) was another important contributor to early immunology. Pasteur, a French microbiologist and chemist was studying chicken cholera when he somewhat-accidentally discovered the process of attenuating, or weakening, microbes in order to create a vaccine. In 1879, Pasteur and his assistant inadvertently let some virus cultures die off before injecting them into healthy chickens. They observed that chickens infected with this weaker sample not only survived infection better, but were then still entirely immune to the disease. Using similar methods, Pasteur developed a successful vaccines for both rabies and anthrax. The Fisher Library holds several works by Pasteur, including a pamphlet which first reported his method of virus attenuation, De l’attenuation des virus (1883).

For both Jenner and Pasteur, successful vaccines came through not only repeated experiments and careful observation, but also a bit of sheer luck. Today’s researchers are working towards a coronavirus vaccine in the face of public pressure and many unknowns. As the University of Toronto's Dalla Lana School of Public Health professor Natasha Crowcroft was recently quoted, the path to a safe and effective vaccine is not always straightforward, but “we’re right to be optimistic.” Indeed, the history of vaccine development shows us that we have reason to stay hopeful that a bit of luck will come in to play in stopping our current pandemic.

- Alexandra K. Carter, Science & Medicine Librarian at the Fisher Library