The infamous outbreak of plague known as the Black Death, which swept through Europe from 1347 to 1351, was just the first in a series of such outbreaks that lasted until the 19th century. Taken together, this series is known as the second plague pandemic. But if this was the second, what was the first?

The first plague pandemic began nearly a thousand years before the second with the Plague of Justinian, which struck in 541-549. It is so named because it occurred during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great. As with the Black Death, the Plague of Justinian was only the first in a series of outbreaks, and the disease returned periodically until the middle of the 8th century.

The most important historical witness to the Plague of Justinian is the historian Procopius, who describes in detail the devastating effects of the disease in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. The information provided by Procopius is of particular interest, however, not just because he witnessed the plague firsthand, but also because he mentions it in two works of widely divergent character: The History of the Wars and The Secret History. In fact, the different ways in which Procopius presents this event in these two works provides an object lesson in the malleability of information, and in particular its potential for politicization. Important editions of both works can be found in the Fisher Library’s collections.

In writing The History of the Wars, Procopius was serving as a kind of court historian to Justinian, and this is reflected in the account of the plague included in this work. While it was impossible for Procopius to ignore the seriousness of the disease – indeed he gives a detailed account of its symptoms and reports that, at its peak, the mortality rate in Constantinople reached 10,000 deaths a day – he could at least absolve Justinian of any responsibility. In fact, Procopius begins his account by stating in highly elaborate terms the impossibility of providing any explanation for the disease, ‘except by referring it to God’. (As we shall see, however, he is of quite another opinion in The Secret History.) Not only is Justinian in no way responsible for the plague, he takes some steps to alleviate the situation, making provision for the distribution of money to those in need. Nevertheless, given the length of Procopius’ description of the plague in The History of the Wars, it is perhaps surprising how small a role Justinian plays in the episode.

If the description of Justinian’s role is a little lukewarm in The History of the Wars, it is certainly not openly critical. The description of the same events in The Secret History, however, is downright hostile to Justinian – as one would expect, given that the whole work is a sustained invective against the emperor and his circle. Quite why Procopius wrote The Secret History is unclear, but the use that Procopius makes in it of the Plague of Justinian is consistent with the overall purpose of the work. Unlike in The History of the Wars, no coherent account of the whole episode is provided; the plague is merely mentioned at various points as evidence of Justinian’s wickedness. In taking this approach, Procopius repeatedly recasts Justinian’s handling of the crisis. In The History of the Wars, no explanation beyond God is given for the plague; in The Secret History, the plague is still sent by God, but it is now implied that it is a punishment for Justinian’s immorality. And while in The History of the Wars Justinian provides some financial relief to the people, in The Secret History we find him extracting from the survivors any taxes owed by their dead relatives. Finally, Justinian is himself described as a plague, and worse than a plague, for while some people survived the Plague of Justinian, no one could survive the onslaught of Justinian himself.

It is hard to know exactly how we should interpret the information on the Plague of Justinian provided by Procopius in his two accounts. The History of the Wars reads as sober history, The Secret History as scandal and gossip, but there are probably some lies – or at least some misinformation – hidden in the former, and some truth in the latter. And however that may be, it certainly says something about how we consume information that while The History of the Wars is Procopius’ most important work, The Secret History is his most famous.

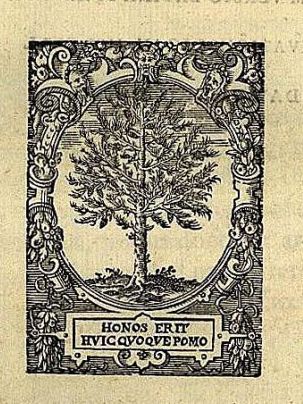

The Fisher holds some of the most important editions and translations of Procopius’ works. This includes the 1607 editio princeps of The History of the Wars, edited by the famous German scholar David Hoeschel. In addition to his work as an editor, Hoeschel was actively involved in the printing business, and together with Marcus Welser he established a printing press ad insigne pinus (‘at the sign of the pine tree’ - see printer's device below) in Augsburg. He had a particular interest in Byzantine literature and also published the editiones principes of Photius’ Library and Anna Comnena’s Alexiad.

The Fisher also has the first editions of two of the most important English translations of Procopius: Henry Holcroft’s translation of The History of the Wars, the first translation of this work into English, published in 1653; and Richard Atwater’s translation of The Secret History, published in 1927. The typeface designer Douglas McMurtrie developed a new face, called Procopius, specifically for this translation, and the Fisher’s copy is signed by both Atwater and McMurtrie. Atwater himself is better known as the author, with his wife Florence, of the children’s classic Mr. Popper’s Penguins.

- Timothy Perry, Medieval Manuscript and Early Book Librarian