The coming effects of climate change, including an increase in droughts, have inspired some to question the value of the innocent-seeming and commonplace grass lawn. A recent opinion piece argues that in the midst of our current climate crisis, “green lawns are terrible for the environment … embarrassingly old-fashioned and out of style.” Manicured lawns might be considered old-fashioned today, and their history can be traced through works on natural history, agriculture and gardening, many examples of which are held by the Fisher Library. The works below show how grass has been studied and cultivated over time and how it ended up adorning the lawns of wealthy landowners. The theme of Science Literacy Week this year – climate – gives us an opportunity to showcase how pressing contemporary issues like climate change can be studied and understood through a historical lens.

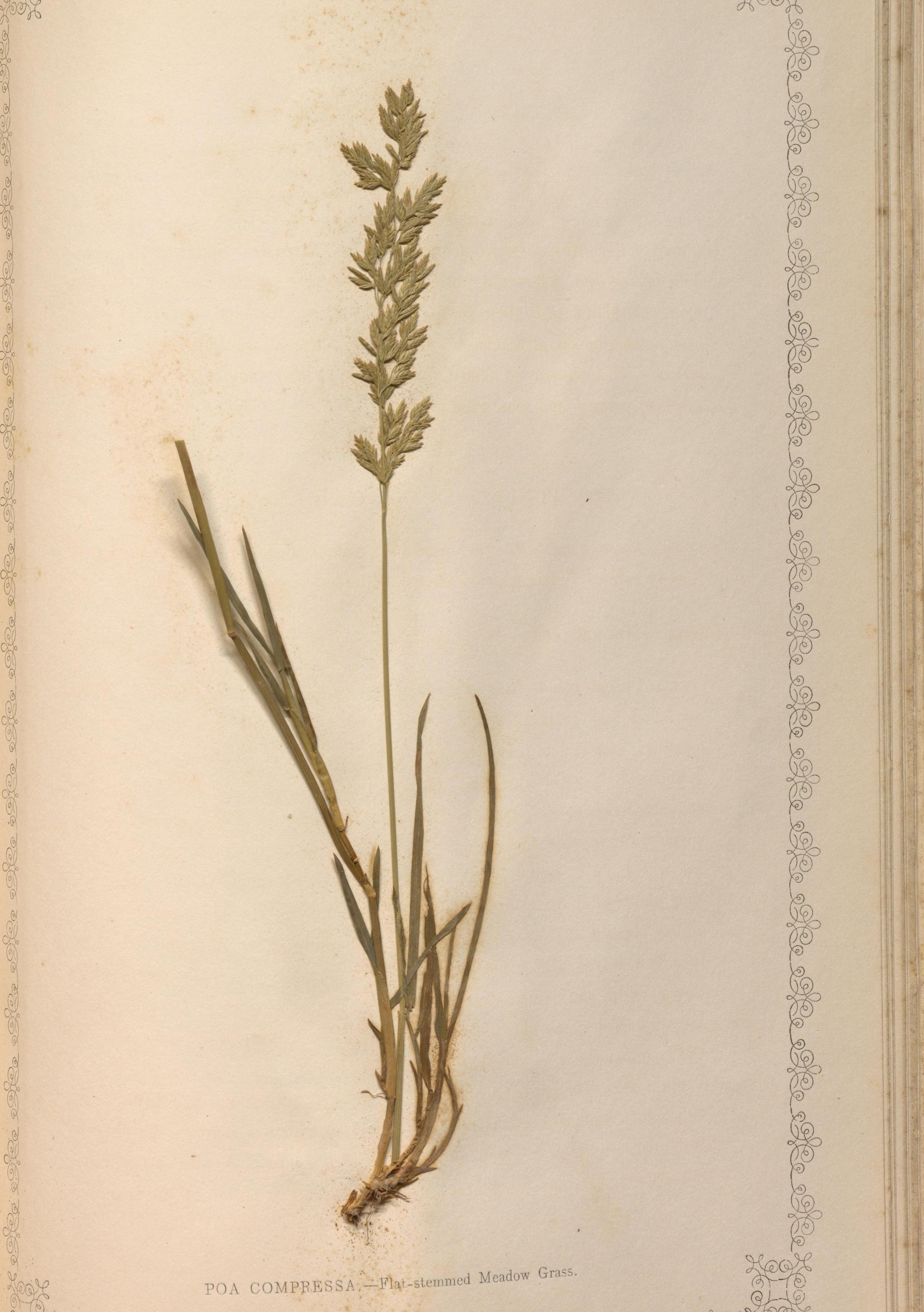

This post was inspired by the library’s recent acquisition of a unique specimen album, Natural Illustrations of the British Grasses, prepared and edited by Frederick Hanham and published in Bath by Binns and Goodwin in 1846. The album contains over 60 specimens of different grass species found in Great Britain, carefully mounted and described in printed text. As with many works of Victorian Natural History, Hanham’s focus is primarily on the beauty and variety found in nature. The grass specimens are accompanied by poems and quotations celebrating the natural world as God’s creation, and his descriptions are more celebratory than scientific:

In the introduction Hanham makes the case for studying grasses and makes a fascinating point: “no plants are more widely distributed over the surface of the globe than the Grasses, extending their range from the equator to the polar regions; and none are more varied in habit, to adapt them to the various circumstance of soil, situation, and climate …” Indeed, it is this adaptability that allowed grasses to proliferate in the wild but also throughout human civilizations.

The Fisher Library has several collections that reflect this, in the form of treatises or manuals on animal husbandry, farming and agricultural methods. These works treat grasses not as beautiful and unique specimens of nature but, like with alfalfa hay, as raw material to be cultivated as food for animals and humans and as material for operating a farm. In The Complete English Farmer, or, A Practical System of Husbandry by David Henry (1710-1792) covers how to plant, grow, harvest, store and use a range of grasses, including which tools, soils and fertilizers should be used to maximize yield:

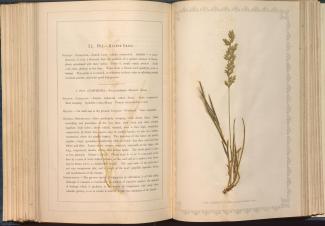

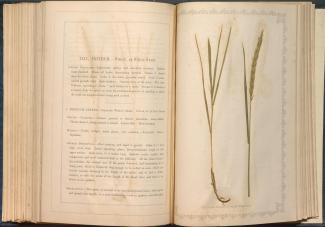

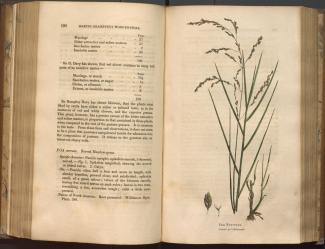

More scientifically, Hortus Gramineus Wobernensis, first published in 1816 by George Sinclair (1736-1834), gives the results of several experiments on the nutritive qualities of different grasses and other plants “used as the food of the more valuable domestic animals.” These experiments and the grasses themselves are described alongside a set of highly detailed, coloured engravings:

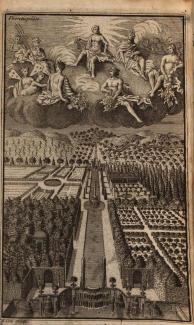

Finally, grasses can also be found in gardening manuals where they are discussed for the ways they can be cultivated intentionally to beautify land. In The Gardner’s Dictionary by Philip Miller (first published in 1731) the author describes in minute detail how to design, plant and maintain grass lawns for aesthetic reasons:

In a fine Garden, the first Thing that should present itself to the Sight, should be an open level piece of Grass, full as broad as the Length of the Front of the Building, which may be surrounded by a Gravel-Walk, for the Conveniency of walking in wet Weather. These Pieces of Grass should not be dividing in the Middle with a Gravel-Walk (as is too frequently seen), for it is much more agreeable to view an entire Carpet of Grass from the House…

- Alexandra Carter, History of Science and History of Medicine Librarian