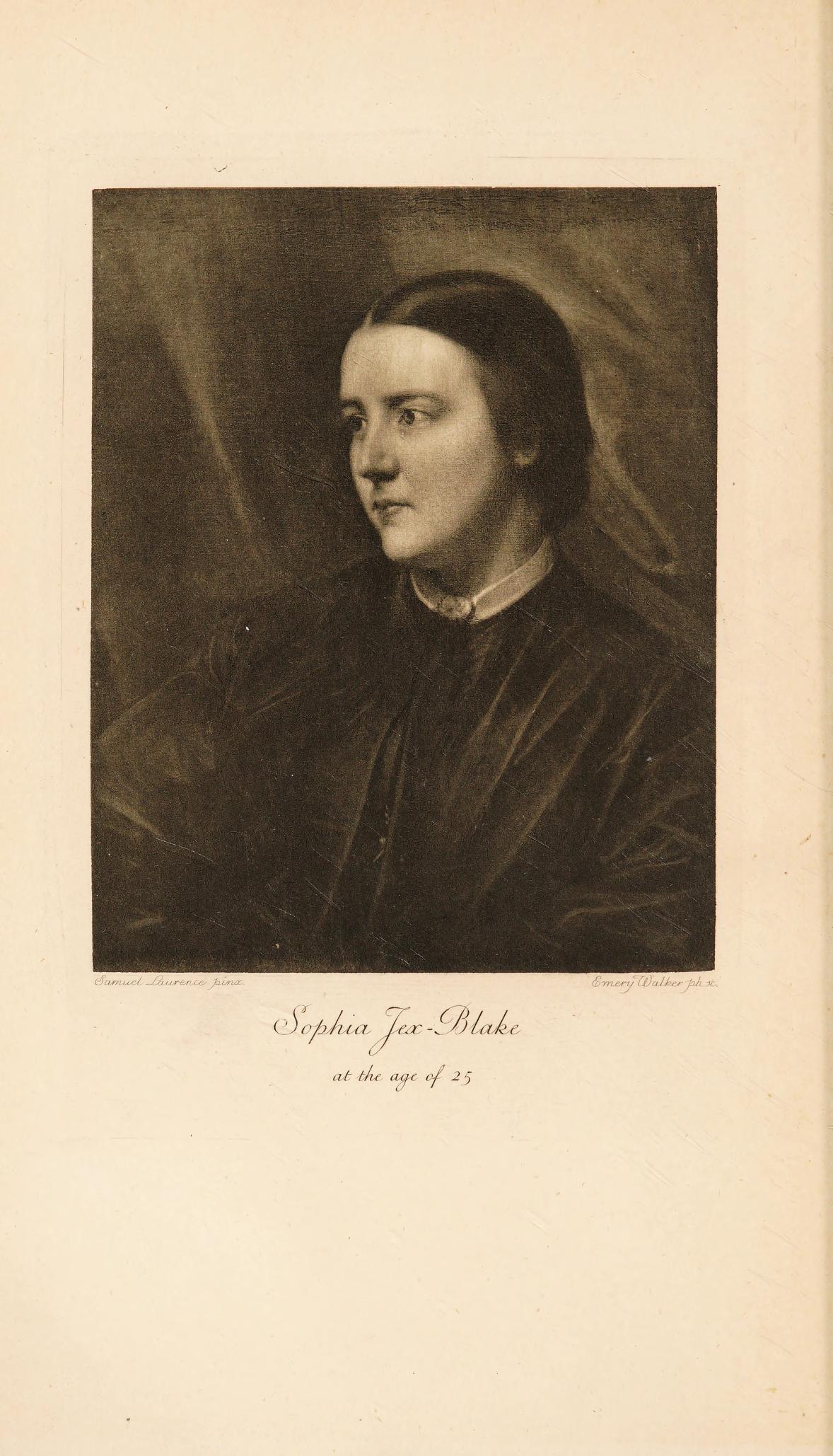

Nineteenth-century Scottish physician Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) devoted her life to the advancement of womens’ rights in the field of medicine. Her career and personal life reveal how the professionalization of modern medicine occurred alongside changing social attitudes about women’s social rolls and sexual identities.

Denied access to professional medical education as a young woman, Jex-Blake and six other women (Isabel Thorn, Edith Pechey, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Mary Anderson, and Emily Bovell) – who became known as the ‘Edinburgh Seven’ – campaigned for nearly a decade for their right as women to attend medical school and practice medicine. The Seven’s work garnered international attention and the support of prominent physicians and scientists, including Charles Darwin. It culminated on November 18th 1870 with the Surgeon’s Hall riot where Jex-Blake and her peers were attacked by male students and shut-out of the Royal College of Surgeons where they were due to write exams in anatomy. The display at the Surgeon’s Hall brought more public support for what was now a movement. After several petitions to medical institutions and government, the Medical Act of 1876 was passed, allowing all medical institutions in the Britain to license qualified applicants as Medical Doctors regardless of their gender.

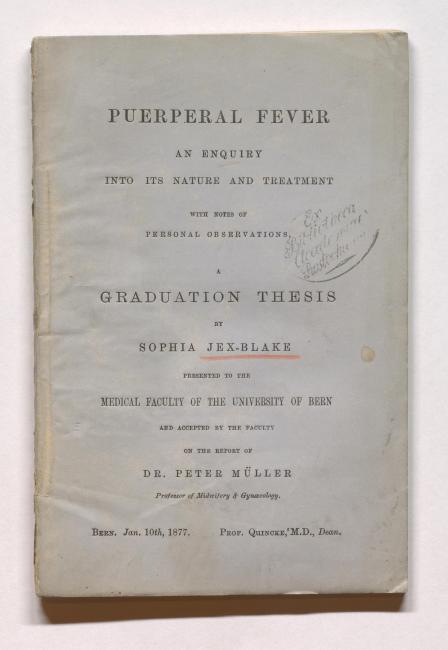

In 1869 Jex-Blake contributed to a volume published by prominent suffragist Josephine Butler with an essay, “Medicine as a Profession for Women.” Jex-Blake appealed in her essay to the early history of medicine, noting references to medicine and women in both The Iliad and The Odyssey, as well as in Renaissance Italy, up until Jex-Blake’s time. She noted, however, that women’s medical knowledge had largely been constrained to female concerns of midwifery and childcare and relegated to realm of the domestic or ‘non-professional’. The Fisher Library has several collections in the history of medicine that trace women’s involvement in medical practice from antiquity to the present day, including a library of works on obstetrics and gynaecology; a collection on pediatric medicine, and several examples of domestic medical manuscripts prepared by women. The Library also holds a copy of Jex-Blake’s medical school dissertation on peurperal fever, one of only five copies in public institutions world-wide. In the dissertation, Jex-Blake herself emphasizes the importance of studying the history of medicine and the history of particular diseases, so as to avoid the dangers of “theoretical pathology.”

Dr. Jex-Blake’s contributions to social reform for women in medicine were deeply entwined with her personal drive for self-determination, as was the case for many of her female peers. Her family disproved of her career aspirations and encouraged her to marry, balking at the notion of their daughter collecting a salary. While marriage may have made things easier for Jex-Blake financially, it would likely have stifled her professional career. More to the point, Jex-Blake recorded early on in her diary as a young woman:

"I said I did not fancy I should ever marry, for I thought I should require too many qualities to meet in the man I could think of as my husband, for it to be likely that I should ever meet such a paragon who could be willing to marry me."

Jex-Blake remained unmarried and perhaps unattached throughout her career, though historians have speculated about the nature of the intimate friendships that developed within the small social world of women who pursued self-determination at the turn of the nineteenth century. Indeed, Jex-Blake’s diary reveals subtle details of very close friendship and parting with well-known social reformer Octavia Hill (1838-1912). Recalling a trip with Hill long after their falling-out, Jex-Blake wrote:

"… our glorious Whitsuntide at Hurst, — Octa and I. The few days (Thursday to Tuesday) pure unmixed heart sunshine. Purer and deeper if possible than that of Wales. […]

The hurried tea, the night mail, the parting hand pressure as the train moved, ‘in the sure and certain hope’—is it blasphemous so to use the words? I think not. There was a glorious churchlike solemnity always on our love. Well!—then the five months’ parting,—hard it seemed then, but painless—heaven—to what came after. Perhaps I am not yet meant to see the ‘why’ of all that followed.... We seemed so helpful heavenwards to each other. Never seemed our love truer, deeper, purer, I know though now that mine could be all three.

Yet with all this wondering, I do and have felt most solemnly. Surely it is best. ‘We shall see in Heaven why it could not be otherwise.’

At least, Octavia, you have never had (in me at least) so true and deep and real a friend as now,—and yet quieter and so stronger."

Jex-Blake did eventually “settle down” – with a fellow woman doctor, Dr. Margaret Todd, for a quiet retirement in rural Rotherfield, but not until physical ailments demanded that she do so after a long career fighting for women’s medical education. Margaret Todd was a doctor – trained at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women established by Jex-Blake herself – but she was also a novelist (she wrote Mona Maclean, Medical Student in 1892 under a male pseudonym, about the life of a female medical student). Following Jex-Blake’s death in 1912, Todd prepared a biography, The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake, from which the above diary selections are taken. Todd, interestingly, never mentions her own appearance in Jex-Blake’s life in her biography. It is worth noting that while Jex-Blake and her peers made significant headway in changing social norms around women in professional roles, at the time of the publication of Jex-Blake’s biography they still could not openly discuss the nature of their relationship.

Nevertheless, the life of Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake and her relationship with Dr. Margaret Todd reflect the shifting professional, personal, and sexual identities of women in the late nineteenth century and the sacrifices made by the women at the forefront of the push for change.

- Alexandra K. Carter, Science & Medicine Librarian