It was exactly one year ago today, St Patrick’s Day 2020, that the doors to the Fisher Library were closed to the public by order of both civic and university officials. Little did we imagine that one year later we would still be working from home, with occasional visits to the building to check on its security or to scan materials urgently needed by researchers working at a distance. Among the requests that I received recently, bringing me physically back into the Fisher, was for a scan of a very rare printing of a poem by William Butler Yeats. This sent me down the rabbit hole of early twentieth-century Irish Revival Literature in which it is so easy to get happily lost. Walking through Fisher’s DeLury collection of Irish literature, of which Yeats’s work is arguably the cornerstone, I was reminded by the numerous spine titles staring back at me that this year marks one hundred years since the conclusion of the Irish War of Independence, a bloody conflict that can be traced back to the Easter Rising of 1916. One can hardly describe the end of the war as peace. It was more of a transitional time as Ireland tried to make sense of its identity, an identity shaped in large part by the Irish poets of the period who wrote out of a love and awe, fear and hope for their homeland.

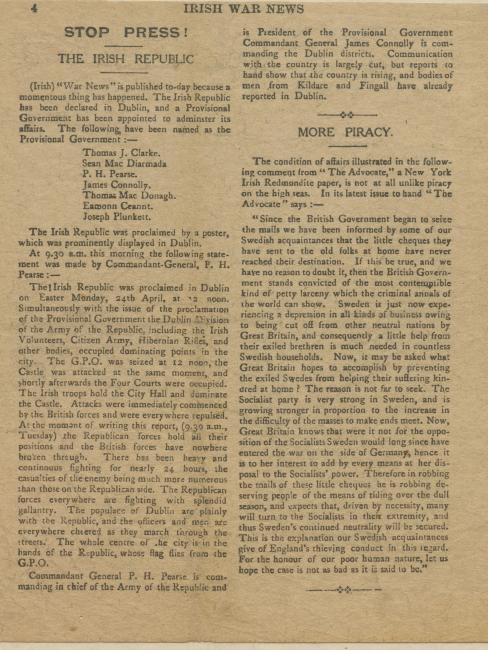

Among the most important artefacts DeLury collected was the sole issue of The Irish War News, printed on the day of the Easter Monday Rebellion itself, 24 April 1916, but not actually published until the Tuesday. Under the dramatic banner of “STOP PRESS”, the writer describes the stirring declaration of an Irish Republic and the appointment of a provisional government. This, of course, is just the beginning of the tragic tale, and in fact hides the reality that a majority of Irish at the time did not support the rebels in their initial attack on British rule. Many had male family members fighting in Irish regiments under British command in the First World War on the Western Front and in the Dardanelles. To them, the uprising was an unnecessary distraction from the task at hand. As the rebels were executed within a ten-day span at the beginning of May, however, public opinion began to sway in their favour and a reassessment of Irish participation in the Great War began to emerge. This feeling was captured in a short verse from the song “The Foggy Dew” which became popular in the aftermath of the British reprisals:

'Twas better to die 'neath an Irish sky

Than at Sulva or Sud El Bar.

Horror at the brutality of the British retaliation was but one piece of the puzzle that would hasten the desire for an Irish Republic. Equally if not more important was the influence that many great authors, poets, and playwrights of the Irish renaissance brought to bear on the formation of a consciously Irish identity and a sense of enduring nationalism.

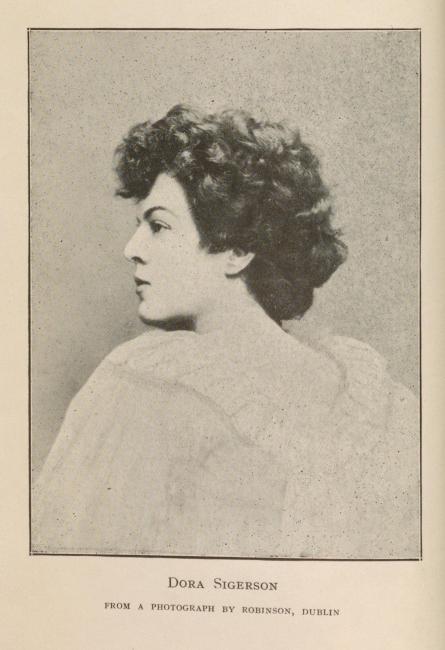

Among these were several of the great female members of the revival such as Lady Gregory (1852-1932), Alice Milligan (1865-1953), and Dora Sigerson Shorter (1866-1918). Each was a cultural nationalist, passionate about Gaelic language and tradition, though they varied somewhat in their political expression. In the year of the rebellion, Shorter (who had moved to London with her husband) published Love of Ireland: Poems and Ballads. The opening verses of her first poem convey the passion she wished her fellow citizens to feel for their homeland:

'Twas the dream of a God,

And the mould of His hand,

That you shook 'neath His stroke,

That you trembled and broke

To this beautiful land.

Already in this poem is a presentiment of what Yeats will write later in the year when, reflecting on the Easter Rising, he states “a terrible beauty is born.” Shorter’s friends claimed that she never recovered from the execution of the rebels, some of whom were author friends like Patrick Henry Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, and Joseph Plunkett.

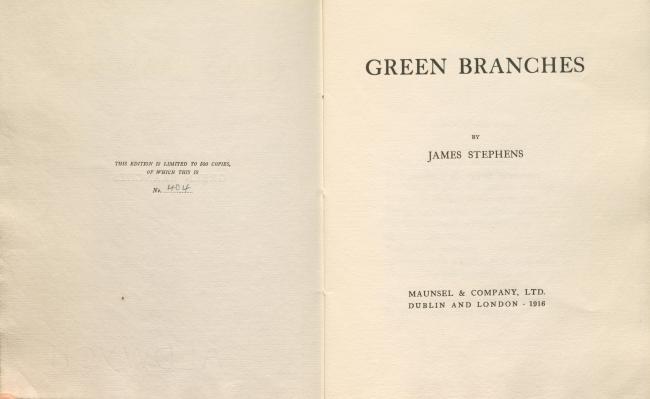

In 1916, another member of the Revival, James Stephens (1880-1950) wrote two books that attempted to explain, in two very different ways, the meaning of the Rising. The first, Insurrection in Dublin was described by The Times Literary Supplement as “a queer, quiet book … with passionate interest.” In many ways, Stephens’ extended poem Green Branches was more influential, however, as it attempts to come to terms with the “terrible beauty” that was dawning over the island, with the concomitant violence that marked the formal beginning of Ireland’s struggle for independence.

Be green upon their graves, O happy Spring,

For they were young and eager who are dead;

Of all things that are young and quivering

With eager life be they remembered :

They move not here, they have gone to the clay,

They cannot die again for liberty;

Be they remembered of their land for aye;

Green be their graves and green their memory

In some ways the work is the very antithesis of the Owenesque pacifist poetry that emerged from the Great War. It did, however, serve to support the notion that the fight for an independent Ireland was a more worthy cause than dying for the tangled politics of European imperialism.

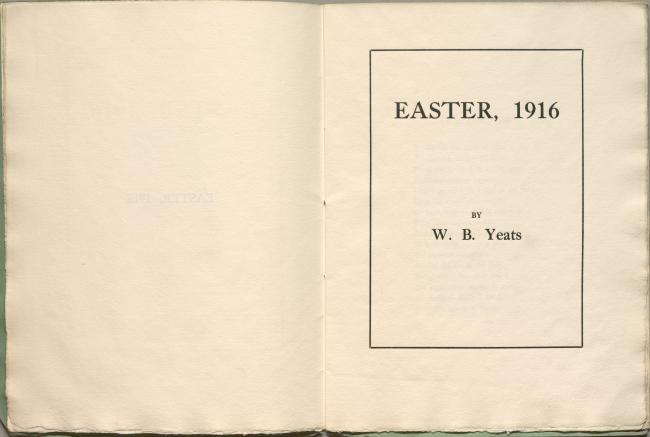

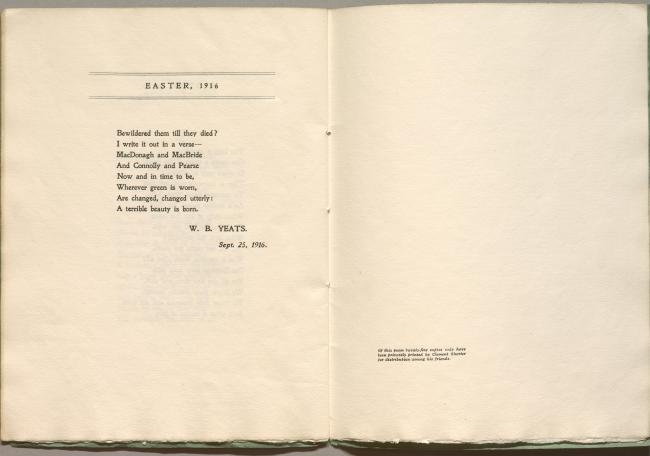

It was William Butler Yeats’s Easter 1916, to which I have referred several times already, however, that is arguably the greatest literary attempt to delve into the complicated meaning of the Rising. Yeats had worked on the poem from the safety of a French retreat throughout the summer of 1916 and wondered whether he should include it as the first poem in his upcoming Wild Swans at Coole. Fearing a hostile British reception if he did, Yeats decided to issue the poem separately in 1917 in a very limited publication of twenty-five copies, printed by Clement Shorter (Dora Sigerson’s husband) and distributed only among Yeats’s closest friends. The Fisher’s DeLury collection holds one precious copy of the lyric that would not be more widely published until 1920.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Not all approved of Yeats’s verse at the time, especially those who vigorously objected to the description of their martyred patriots as men who had died bewildered from having loved their homeland too much. As time passed, however, that lack of sentimentality became one of its chief recommendations, and still speaks to those who value truly heroic poetry, whether Irish or not.

So, on this first anniversary of our own generation’s hardship, I do not compare the privations we have experienced over these past twelve months to those that Yeats, Shorter, Stephens, and the other great Irish poets tried to capture in their verses. They are completely different in scope and scale. On this St Patrick’s Day, however, their poetry (like all great poetry), can help us put what we are currently living through into some kind of perspective. I close today with the words of the great Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) who was heir to the Irish literary revival. His subject may have been ancient Troy, but his meaning is universal and speaks to so many of our immediate concerns today.

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave,

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

So, hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracles.

And cures and healing wells.

- P.J. Carefoote, Department Head