Among the more impressive and unusual items in the Fisher Library’s Tennyson collection are several very large editions of Idylls of the King illustrated by Gustave Doré (1882-1883) for the publishing house of Moxon. Unlike the famous 1857 Moxon octavo of wood-engraved illustrations by various artists, the Doré Idylls were illustrated by a single artist, engraved in steel, and produced in a large, folio format. Whereas single-volume collections with wood engravings or chromolithography were much more fashionable in the 1860s, the Doré Idylls were a series of separate books, issued annually over several Christmas seasons, much like the gift book series produced by Letitia Landon and the Countess of Blessington in the 1830s. Since gift books were typically bought by men to give to women, most contemporary gift book versions of Tennyson’s poetry had feminized associations of prettiness or emotional directness; the overall effect of Doré’s stark and often grotesque interpretation of Tennyson’s epic, on the other hand, was masculinizing. Impressive and attractive to the casual reader, these Doré Idylls differ from other midcentury Tennyson gift books in a number of ways that might interest researchers.

The Idylls of the King were a series of individual poems, unified in their Arthurian subject matter, that Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) began to publish in 1859. The first volume contained four poems, each named after a female protagonist: ‘Enid’, ‘Vivien’, ‘Elaine’, and ‘Guinevere’. The unillustrated 1859 Idylls were tremendously popular, selling ten thousand copies in six weeks, with a second edition issued six months later, and six additional editions produced within a decade. Comprised of four separate narratives of roughly equal length, the 1859 Idylls collection lent itself to re-publication in separate volumes. Gustave Doré then, was tasked with illustrating the separate poems as a series, to be issued annually for the Christmas market. Doré was an imaginative, talented, and incredibly prolific illustrator, painter, and sculptor who had recently relocated to England after twenty years of success in France. Largely self-taught, he had begun his career as a cartoonist for French newspapers; Doré’s style tended to be monstrous, voluptuous, or irreverent. He was already very well known to the British public, particularly for his New Bond Street Gallery and his editions of Rabelais (1854), Don Quixote (1860), Dante's Inferno (1861) and the Bible (1866). He was contracted to illustrate the Idylls by James Bertrand Payne (1833-1898), the manager running Tennyson’s publishing house after the death of Edward Moxon (1801-1858).

The Doré Idylls were sold at extravagant prices and produced at great expense. Although wood engraving had become the industry standard, and Doré’s previous illustrations had all been published as wood engravings, the Idylls were to be produced on steel engravings, suggesting plans for an enormous run. The scale of the volumes, printed at folio size (43 cm x 31 cm), announced their luxuriance and purpose of drawing room display. Moreover, as Jim Cheshire reports, the illustrated Idylls were offered in a wide range of formats to appeal to luxury gift buyers of differing means:

In addition to the basic edition, ‘proof’ editions of the engravings were published and the images and text were also issued loose in a portfolio. [. . .]. The standard edition of Elaine was published at 21s, the ‘proof’ edition at 63s, and for 105s an enthusiastic customer could buy the ‘artist's proofs’ edition with images signed by Doré and Tennyson. Payne also issued editions with [. . . ] tipped in photographs [of Doré’s drawings].[1]

Using steel engraving rather than wood engraving raised the cost of production, as did the elaborate photographic format. Payne borrowed against the business to raise money for the enormously expensive project, weakening the firm’s stability.[2] Because Tennyson’s contract for the edition would only provide him with payment after the costs were met, he was paid very little from the Doré Idylls. Having over-invested in the series, Payne publicised it aggressively, causing great discomfort of the Poet Laureate. Keen to protect the prestige of his poetry from commercialization, Tennyson was provoked to leave the house of Moxon in the spring of 1868, ending a business relationship of over thirty years.

Critical responses were mixed. As W. H. Herendeen observes, Doré's popularity, publicity, and productiveness gave him mass appeal but also ‘aggravated critical opinions: ‘serious’ critics tended to reject him instinctively, while his advocates, however intelligent, were inevitably compromised by the wave of popular enthusiasm’.[3] The Times review was representative when it ‘pointed out certain flaws in Doré’s designs (his battle scenes, it was suggested, show individual figures in unrealistic poses and his fairies are far too fleshy and carnal), but these faults are outweighed by the fact that Doré brings his own colour and harmony to the images’.[4] The Leisure Hour reviewer enjoyed Doré’s ‘mastery of picturesque effects’, but noticed several flaws, including ‘marks of haste’ and a lack of fidelity that was inevitable in an artist who drew from imagination and memory rather than using models (‘his rocks are often unknown in geology’). [5] The reviewer for Belgravia praised the illustrations, but, referring to the photographs of Doré’s drawings in the special edition, regretted that they had been engraved on steel rather than wood.[6] John Ruskin (1819-1900), on the other, hand, was horrified ‘that our great English poet should have suffered his work to be thus contaminated’, by an ‘impure’ illustrator like Doré, describing the results ‘merely and simply stupid; theatrical bêtises, with the taint of the charnel-house on them besides’.[7]

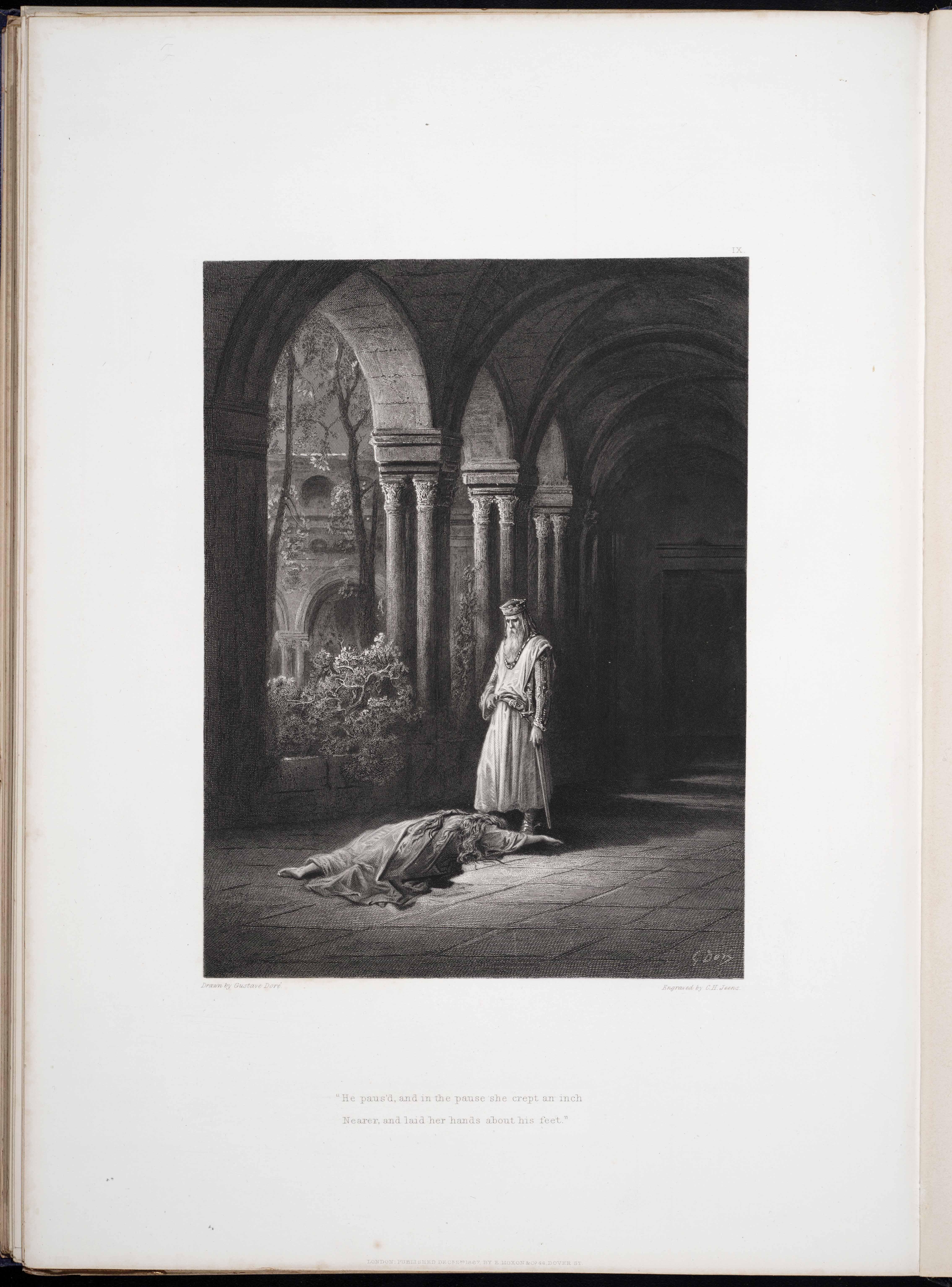

It is difficult to share Ruskin’s horror, but Doré’s illustrations for the Idylls do often create an atmosphere of mystery or disturbance. His use of light evokes a sense of the spectral or supernatural; the speckled appearance of the steel engravings (unlike the grainy finish of wood engravings) contributes to the effect. Doré’s predilection for coarse details is particularly disruptive in such a context. Moreover, the proportions of Doré’s illustrations provide a deceptive first impression of tranquility, which is disturbed in the finer details. The picturesque landscapes of forest, cave, or castle towers dwarf the human figures, delaying recognition of small, unsettling details. For example, in ‘King Arthur Discovering the Skeletons of the Brothers’, it is only after the viewer perceives the figure of the armour-clad king and his graceful horse, framed by a halo of cloud and a backdrop of castle and cliff, that the decaying corpses at his feet in the foreground become noticeable. In this plate, as in the frontispiece of Elaine’s body on the barge, the bodies are unnaturally elongated, creating a surreal sense of distortion.

There is little ‘prettiness’ in Doré’s Idylls. A decidedly masculine effect is created by Doré’s taste for grotesquerie and the aggressive insistence on disturbance in plate after plate. The impression of an anxiety to appear ‘manly’ is reinforced by Doré’s failure to make the female figures, particularly Elaine, convincing, and by his frequent portrayal of women in postures of supplication. The ‘grim realism, often even savagery and coarseness’ which struck Victorian reviewers in Doré’s illustrations may even have provided a counterbalance to readers dissatisfied with the ladylike decorum of Tennyson’s Camelot.[8] As Alan Lupack has observed, the popular ‘1859 volume, with its emphasis on the female characters, had a tremendous impact on the development of the Arthurian legends and on the popular reaction to them’, spurring the ‘interest of female illustrators’, but also provoking some critics to construe Tennyson’s depiction of Camelot as effeminate.[9] Tennyson’s sensitivity to such interpretations may have prompted some of his revisions of the Idylls: with the exception of ‘Guinevere’, the titles were changed so as to draw attention to male counterparts of the characters, with ‘Vivien’, for example, becoming ‘Merlin and Vivien’. The printing method may also have made a difference. Because steel engravings were used, the illustrations were full-page plates separate from the leaves of the text. Not co-existing on the same page as Tennyson’s words, these images were much less obtrusive than wood engravings. Certainly, Tennyson was pleased with Doré’s masculinizing gloss on the Idylls, expressing his pleasure in them, and writing a letter of thanks to Doré in schoolboy French in February of 1867.[10] The book buying public agreed. Doré’s illustrated Idylls were a popular success, becoming the ‘definitive Christmas books of their respective years’.[11]

Volumes available at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library:

Alfred Tennyson. Guinevere. London: E. Moxon, 1867. Illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Alfred Tennyson. Vivien. London: E. Moxon, 1867. Illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Alfred Tennyson. Elaine. London: E. Moxon, 1867. Illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Alfred Tennyson. Enid. London: E. Moxon, 1868. Illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Alfred Tennyson. Les idylles du roi : Énide, Viviane, Élaine, Genièvre. Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette, 1869. Translated by Francisque Michel (1809-1887). Illustrated by Gustave Doré.