Towards the end of the last century, during the few brief years that I spent teaching high school history, nothing heralded the long-awaited coming of summer vacation for me more than the annual erasing of the textbooks. On one glorious June day every year, students would sit in my class, pencil and ink erasers in hand, going page by page, removing (as far as possible) any annotations that they had made before returning the books to me forever. Most of these were innocuous underlinings, exclamation marks, or arrows pointing to the more important passages they wanted to remember in preparation for examinations. Occasionally, but rarely, an opinion or two crept in, such as "this is garbage" … or far worse in some cases. Today, when I teach classes at the Fisher, and students comment on the great amount of ancient marginalia that they find in our books, they will often ask why we think so highly of these notes, when they had been told never, ever to write in their books. My routine answer is, "Well, the people who read this volume three hundred years ago, like you, may also have sometimes written 'this is garbage' in their margins too; but then, they went on to explain exactly why, and that’s what makes the difference."

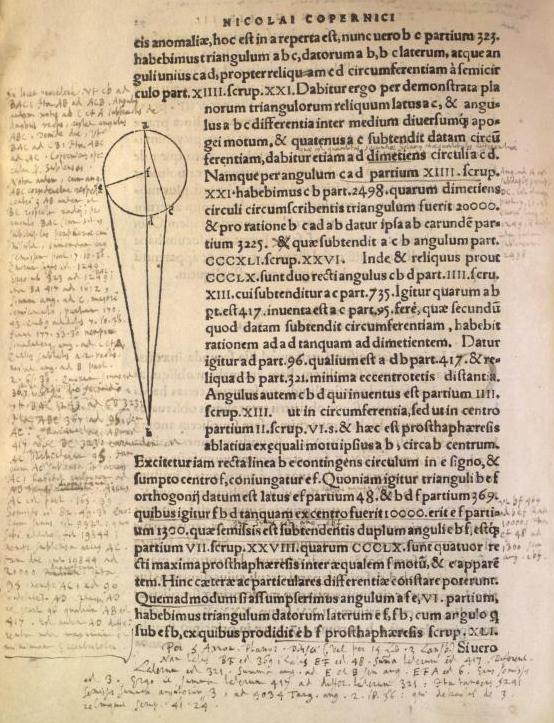

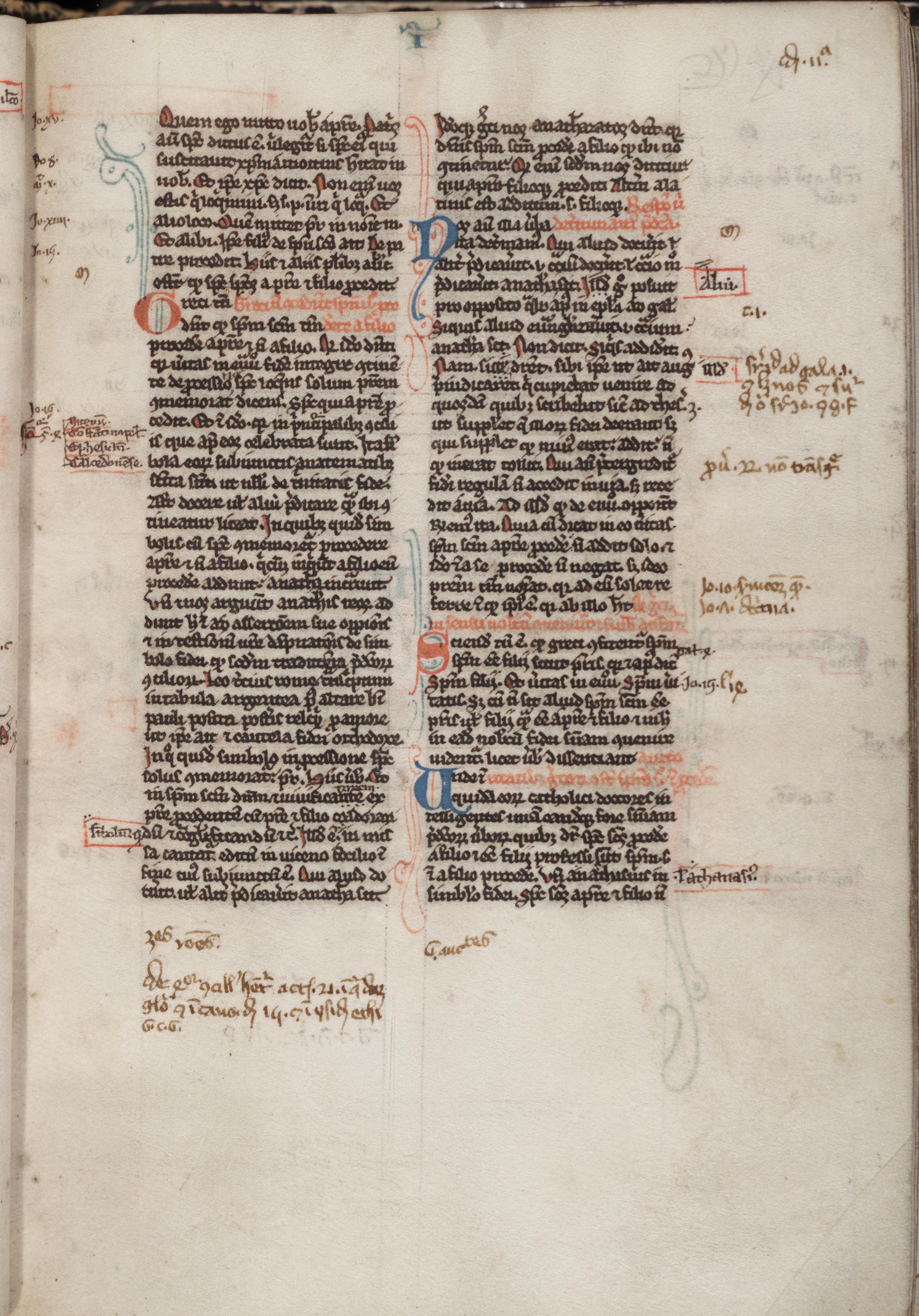

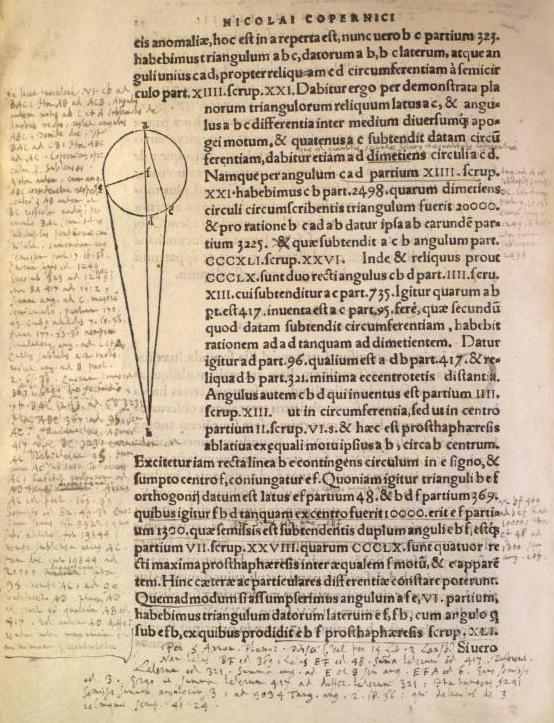

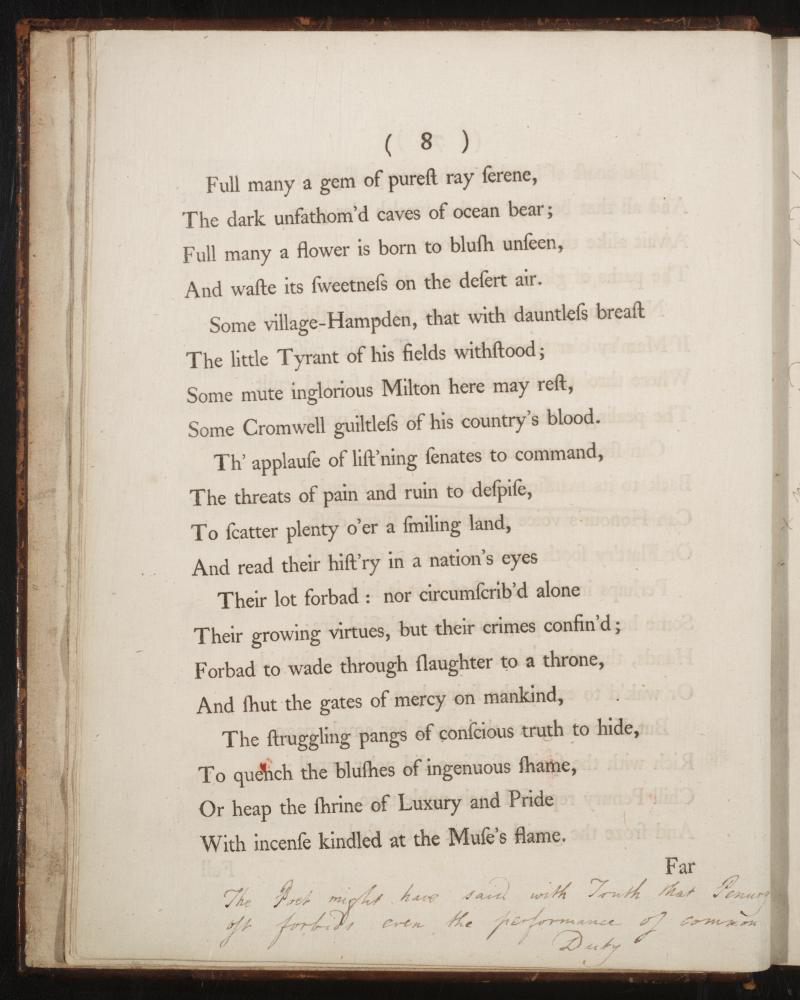

Marks in books record long-forgotten readers’ considered interactions with their texts. They remain witnesses to insights that otherwise would be lost. The student glosses that run through Peter Lombard’s Sententiae dating from the thirteenth century, for example, as they try to make sense of a theological argument see above); the musings of the sixteenth-century annotator of our 1566 copy of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus, as he confronts the heliocentric system for the first time in history (see below); General James Wolfe’s thoughts on Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard that he had with him, and reputedly read from, on the night before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (also below): each of these can open windows into understanding the ways in which books were read and how they influenced the development of ideas among ordinary users.

Hand-written marginalia in books has become a serious area of study in recent decades, thanks in no small part to the 2002 publication of the book aptly titled Marginalia, researched and written by a great Friend of the Fisher, Professor Heather Jackson. She notes that there was a shift over the early centuries of print from readers simply leaving private idiosyncratic marks or impersonal additions on a page to actually engaging with their texts, sometimes in an argumentative way. As the private ownership of books increased, so too did the willingness of readers to annotate them in more meaningful ways. During the Reformation period, for example, many readers engaged with their texts in order to support or detract from the doctrine found therein. A book could, of course, simply be destroyed; but by annotating it, the reader could "publicize error in the name of orthodoxy."

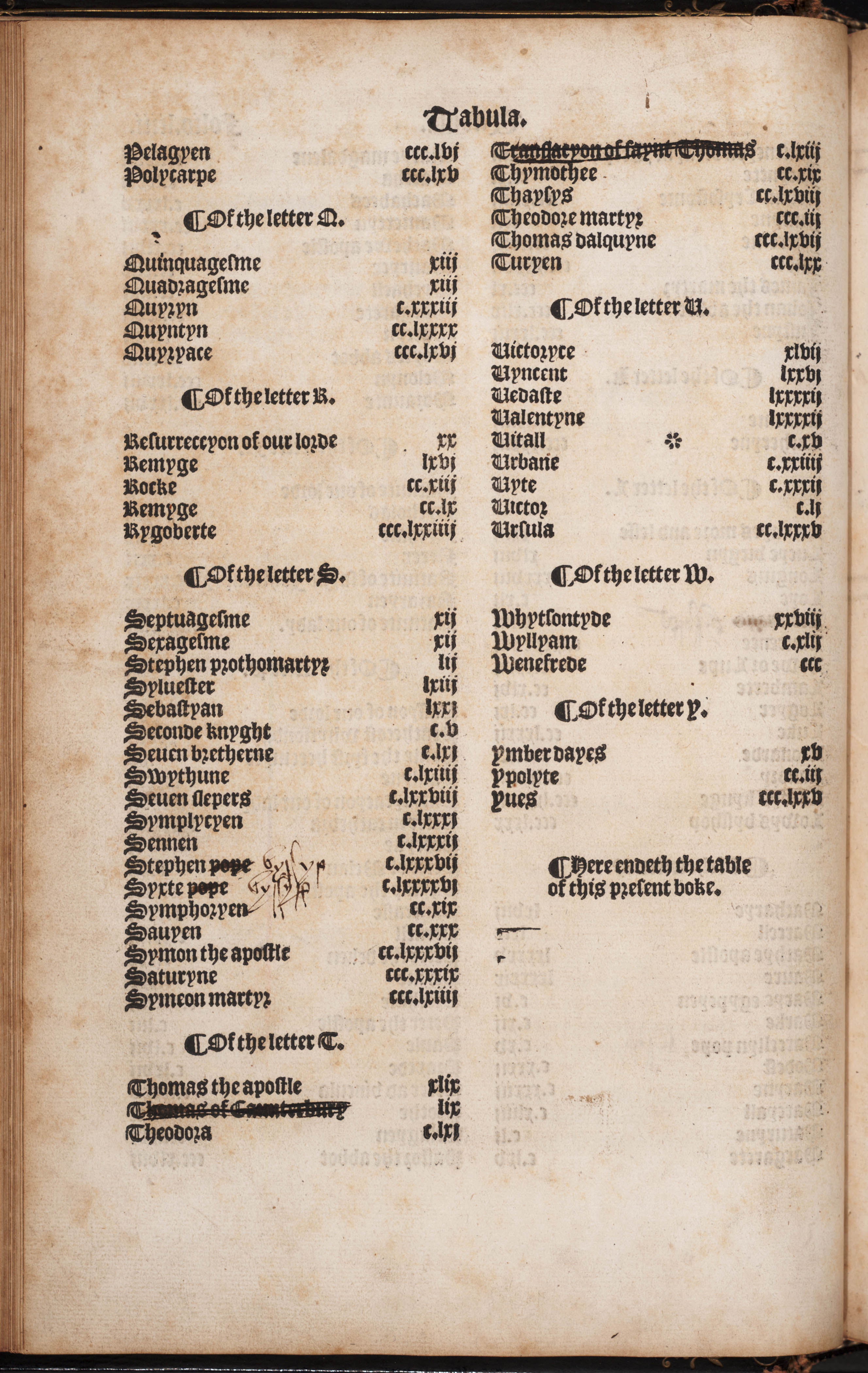

Such is the case with the subject of my latest audio-visual lecture that I have entitled "The Legend, the Virgin, and the Censor: An English Reformation Mystery". It begins with arguably the most popular book of the Middle Ages, The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, and looks at how the Fisher’s copy of the last edition printed in England before the Reformation, in 1527, was used and abused: edited and censored by one owner, then disparaged by another, and yet it survives. By examining the annotations, and the context in which they were made, we can experience vicariously the tensions created when two religious and political orders clashed during the Tudor Reformation.

- P.J. Carefoote, Head, Rare Books and Special Collections