Each week, the Fisher Library highlights an item from one of its many collections digitized online on the Internet Archive. This week, Rachael takes a look at a book from our Biodiversity Collection.

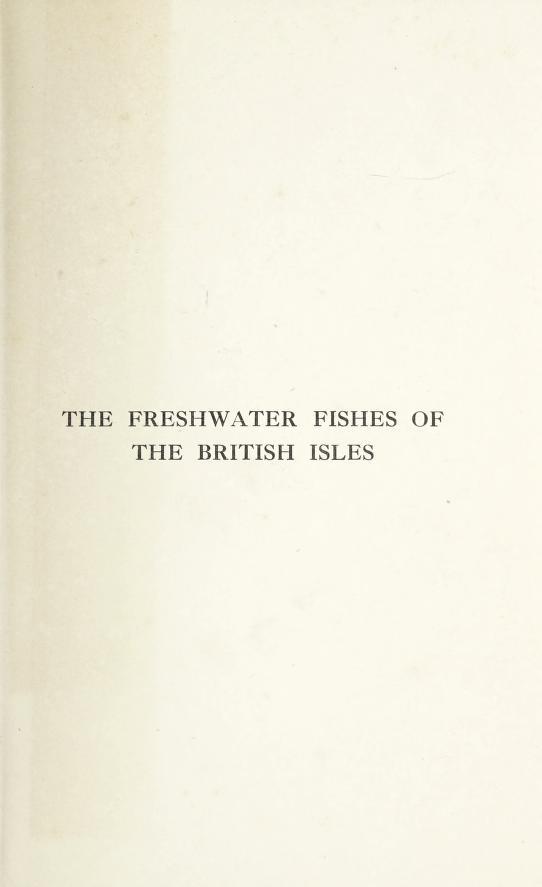

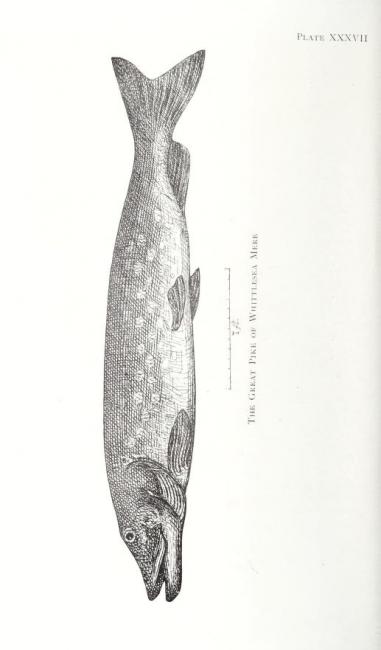

The second week of August has rolled around, and we have reached the dog days of summer. Many of us are trying to fit in our favourite summer activities before the school year starts or before the weather begins to turn to fall. Whether it’s camping, swimming, hiking or fishing, summer activities always hold a special place in our hearts. This week, we are taking a look at The Freshwater Fishes of The British Isles. The book was written by Charles Tate Regan, an assistant in the zoological department of the British Museum. It was published in 1911 and contains 287 pages, including 37 leaves of plates.

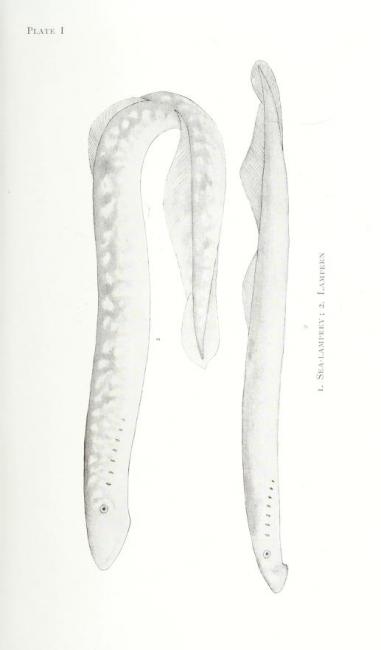

The book begins with a brief preface, explaining the types of fish that the reader will encounter in the coming pages. Following the preface is a Table of Contents listing each chapter of the book. Chapters are divided by the type of fish. There is also an introduction, a chapter on the geographical distribution of the fish, an appendix, and an index. There is also a list of illustrations and their corresponding page number. The introduction begins with a definition of the fish. “The word fish is often applied in a popular sense to any animal which lives in the water, but zoologists use the name only for aquatic animals which belong to the great group of vertebrates.” Here, the author explains the important biological difference that sets fish apart from other water dwelling creatures: “All vertebrates which live in the water are not fishes, but only those which propel and balance themselves by means of fins and obtain oxygen from the air dissolved in the water by means of internal gills.”

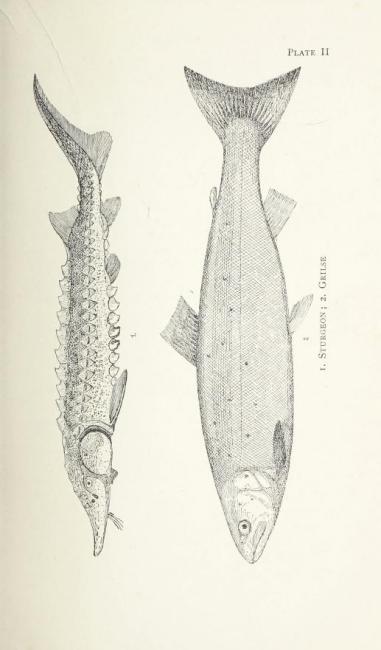

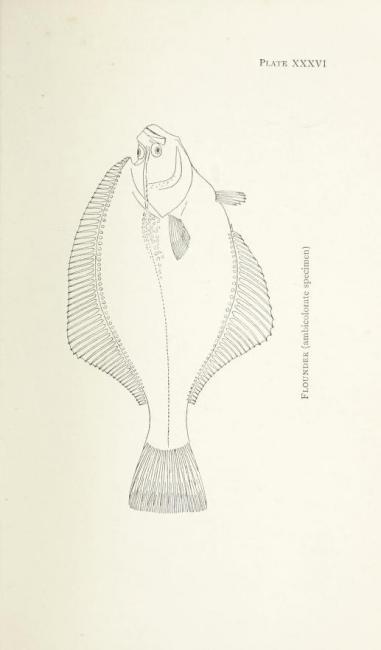

The subsequent chapters of the book are all devoted to a single kind of fish. For example, Chapter Two is on the sturgeon and contains information on its class, subclass, the sturgeon family, its size, food habits, and more. Regan explains that usually only “solitary stragglers” of the sturgeon family are found in British waters because they prefer much larger rivers than any they have to offer, although they are not completely rare. Other chapters follow a similar pattern.

The final chapter offers some insight into the geographical distribution of the freshwater fish discussed in the book. The author conjectures that the first fishes of the freshwaters of Britain became so because they were leaving the ocean in search of food or to escape predators. The last 31 pages of the book contain ads for other publications by the company that printed the book. A full list of summer reading for the enthusiastic reader - when they are not fishing, of course.

- Rachael Fraser, TALint student