Every Monday, we feature an Internet Archive Book of the Week, which will highlight an item from the 25,000 or so Fisher items that are freely available on the Internet Archive. This week, Samantha Summers takes us to Italy

Having spent a few weeks in quarantine and largely confined to our homes, it is only natural that we might become preoccupied with thoughts of faraway destinations and exciting travel. Turning to travel guides is an excellent way to escape to a thrilling new county and city without leaving the comfort of our homes. It is in this spirit that this week’s Internet Archive Book of the Week is Central Italy and Rome: Handbook for Travellers, by Karl Baedeker.

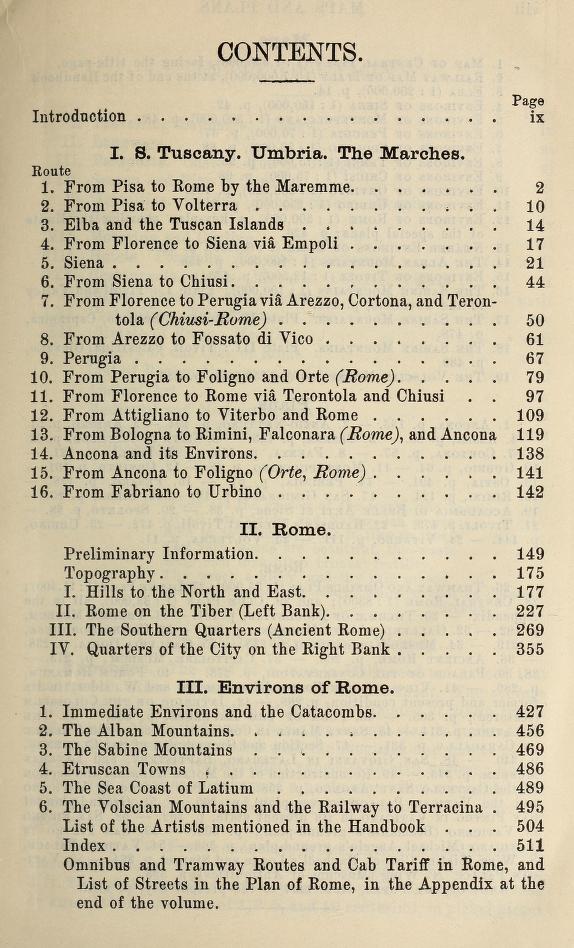

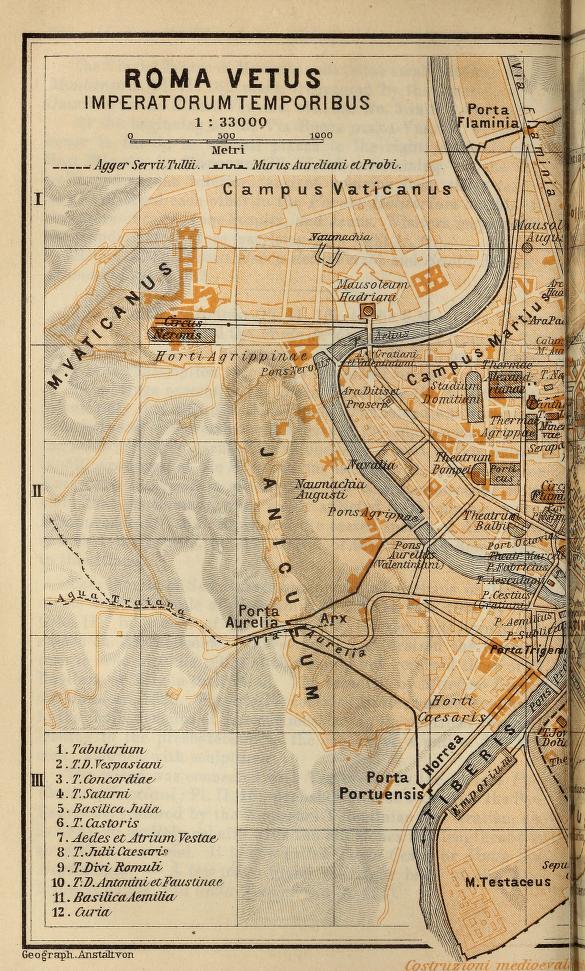

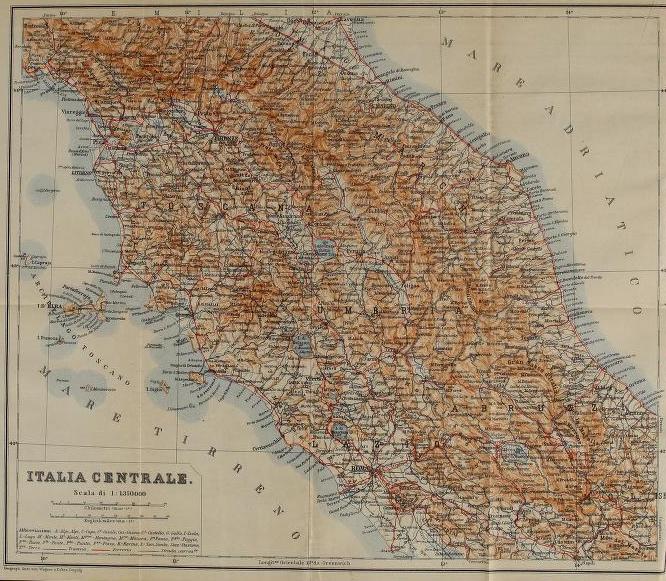

This is the fifteenth edition of Baedeker’s Central Italy and Rome, and was published in 1909. This detailed guide contained everything a traveller may need to navigate central Italy, including dollar conversion guides, notes about language, can’t-be-missed destinations, and helpful maps. At 780 pages long (including a lengthy introduction), it certainly contains a lot of information about Italy. Compared to the travel guide books of today, however, it is difficult to imagine wanting to carry a tome of almost eight hundred pages across the Tuscan countryside.

This guide begins with an introduction to Italy as a whole, with information regarding the cost of travel in Italy, passport and customs requirements, public safety measures and information about common crimes, travel and accommodations, and even the impact of the climates of Italy on the health. This is followed by essays on the history of Rome, ancient Italian art, and medieval and modern Roman art. This text then proceeds to give travel tips for Tuscany, Umbria, the Marches, Rome, and its surroundings.

While much of the contents of this travel book are similar to travel books today, its presentation is distinctly different. Today’s travel guide books include maps every few pages, star systems for rating hotels, and bright colours. Meanwhile, Central Italy and Rome gives no hotel names, but offers helpful tips like, “The second class hotels… are thoroughly Italian in their arrangements, and, though generally provided with good and clean beds, are in other respects less comfortable than those of the first class” (p. xix). Clearly, the travelers of the early twentieth century had to make do with only general advice rather than the detailed tips Fodors guides give us today.

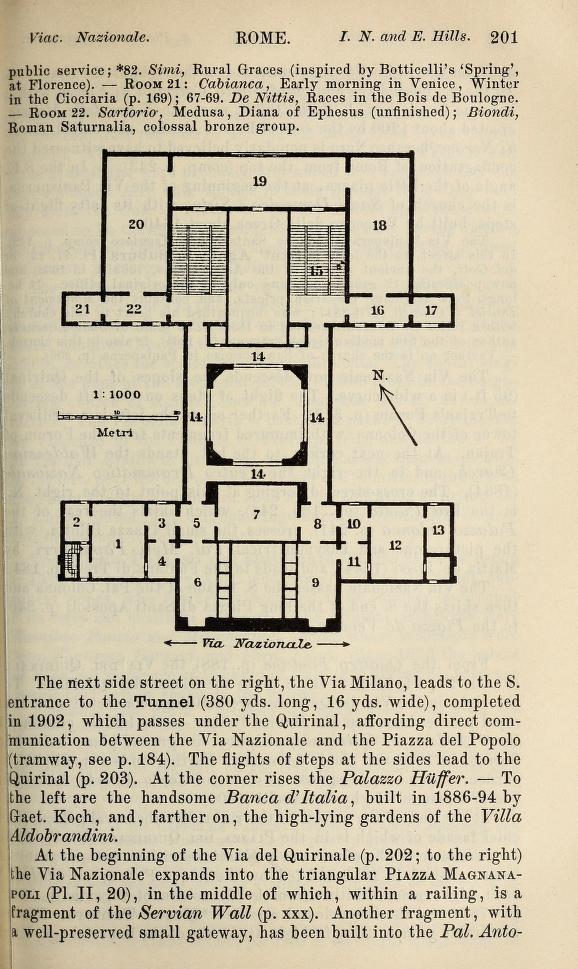

One interesting feature of this text which is less common in travel guides today is floor plans of major destinations. For example, page 201 shows this floor plan (above) of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, making it easier for tourists to plan out their visit to this important gallery. Additionally, where modern travel guides might include photos of major tourist sites, throughout this text you can find the odd illustration of the reliefs of important destinations. This one below features the famed Roman Forum.

By reading texts like this, we can learn a great deal about what people found interesting in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century. It is worth taking time to compare what we think is important to know about a travel destination today with what was considered must-know information in the past. It is also interesting to examine how travel guides functioned before it became common to use photographs in them, and how travel writers could give tourists helpful instructions without relying heavily on any sort of images.

We would love to know which destination you’ve been dreaming of this quarantine. Perhaps we have a guide to it tucked away in our Internet Archive. If so, then perhaps one day you can download that guide and take a trip, using the same kind of directions as a traveller would have had a century ago.

- Samantha Summers, Fisher TALInt student