Every Monday, the Fisher Library highlights an item from one of its many digitized collections on the Internet Archive. This week, Rachael takes a look at a short children's book from our chapbook collection.

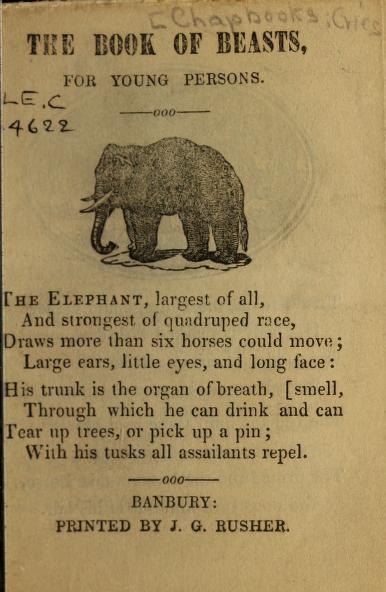

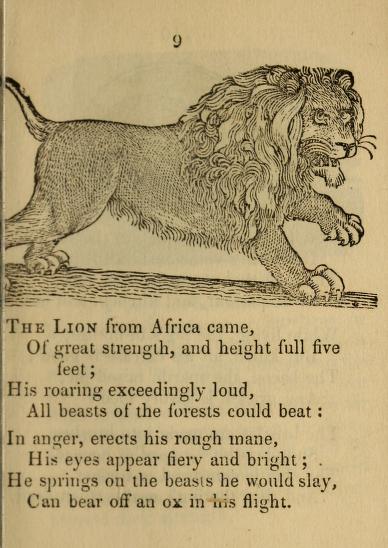

Anyone who spends any amount of time with young children is likely familiar with the enormous genre that is children’s books. Whimsical stories and colourful illustrations that more often than not contain some kind of educational or moral lesson. A common theme amongst children’s books is animals, and it is the subject of the Joseph Crawhall chapbook for this week. “The Book of Beasts, for Young Persons,” is a brief sixteen pages, yet it is filled with images of animals from around the world. While the book is quite short, each page is dedicated to a different animal each with an illustration and information about it. The Fisher Library’s copy does not appear to have a title page, so there is little bibliographical information about the book. The collection of Joseph Crawhall chapbooks contain approximately 600 items, mostly from the first half of the nineteenth century, but many (including this one) are undated. The very first page available for this chapbook states that it was published in Banbury and was printed by J.G. Rusher.

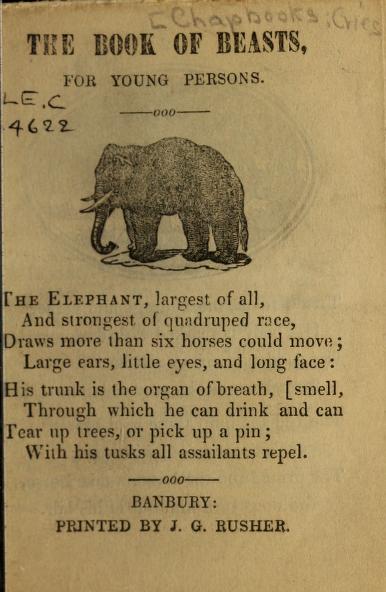

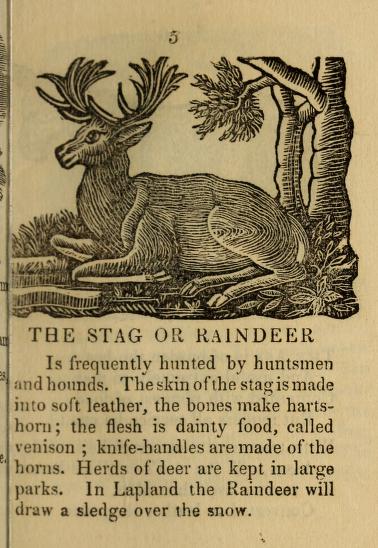

The choice of animals represented in “Book of Beasts” appears to follow no pattern or theme. The images jump back and forth between creatures from the jungle to farm animals to household pets. With all of the animals featured a brisk write-up is included to provide information about it. Most contain basic information, while others the bio reads like a poem. “His trunk is the organ of breath, through which he can drink and can tear up tree, or pick-up a pin; with his tusks all assailants repel.” This is the description of the elephant that begins the book. The other “beasts” in this book include a tiger, rabbit, cow, raindeer [sp], the donkey which is referred to in this book as “the ass,” sheep, horse, bear, the pig, and more. The book ends abruptly with a picture of a camel and what looks like an antelope on the back page with no write-up.

The ways in which the animals are described paints an interesting picture of how they were perceived in the nineteenth century. Many are designated by their usefulness to humans. The sheep is depicted as a “most useful animal, its flesh is excellent food, and its wool supplies us with warm clothing…” For the pig the description is even less generous, and it concludes by stating that pigs are only useful when dead.

While there have always been stories for children, children’s books are a late addition to modern literature. There is evidence in fifteenth-century manuscripts of stories written for children of royal families containing fables with lessons on manners and safety. Later in the eighteenth-century is when fairy tales as well as songs and other oral fables that later became part of children’s literature can be traced. The late nineteenth and early twentieth-century are often known as the “golden age of children’s literature” because many classic children’s books were published during this time. Children’s books encompass an enormous genre, but many have some kind of educational value in common. The outrageous stories and intricate illustrations are there to encourage children to take an interest in books and reading.

While it is a far cry from “what does a cow say?,” the “Book of Beasts” contains all aspects required of a children’s book: educational value, illustrations, and many interesting stories. Although, you may want to skip the part about where bacon comes from when reading to a little one!

-Rachael Fraser, TAlint student