Every November, Canada marks Remembrance Day, a solemn occasion to remember the loss, destruction and trauma wrought by war. The First World War ended 103 years ago and today there is now almost no one living with firsthand knowledge of the event. Accordingly, we rely on letters, diaries, photograph albums and scrapbooks to provide personalized accounts of what life was like in the trenches, on the hospital wards, or on the homefront. The Fisher has a rich collection of such personal stories, which provide a valuable and individualized historical perspective. However, these primary sources also demonstrate an environment of near-constant horror and death; an environment that is impossible for most of us to imagine living through.

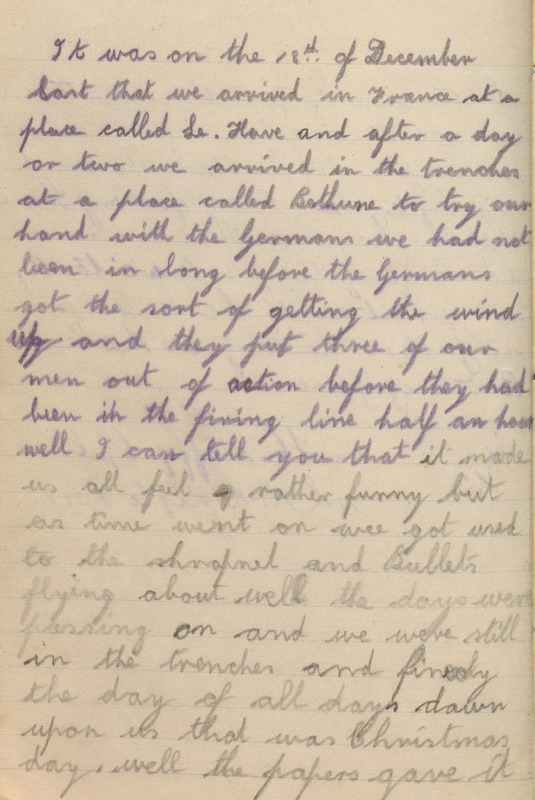

Private Bateman, an English private hospitalized in 1915, wrote an account of his first days in the trenches in Nurse Wenonah Durant’s notebook.

They put three of our men out of action before they had been in the firing line half an hour. Well I can tell you that it made us all feel rather funny but as time went on we got used to the shrapnel and Bullets passing on and we were still in the trenches.

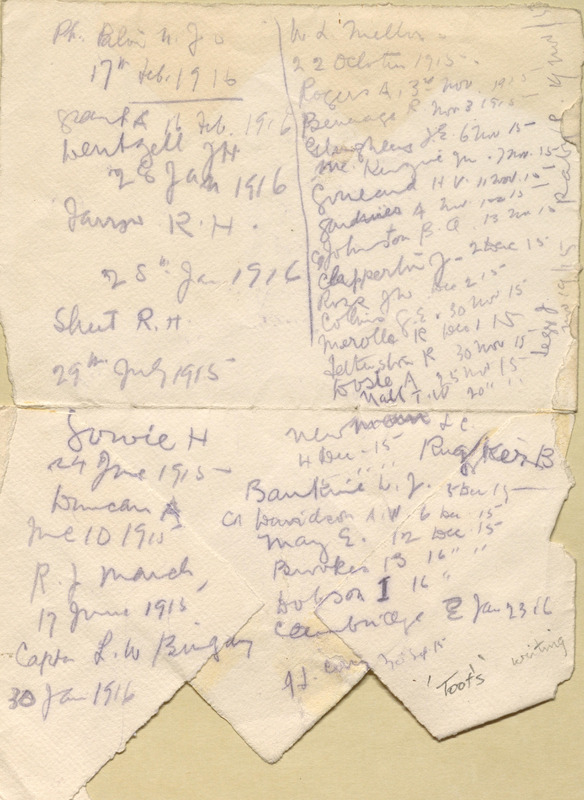

R.G.E Leckie (1869-1923), the commander of the 16th Battalion CEF, kept an envelope, where he jotted down the names and dates of those that had died under his watch, over the span of nine months in 1915 and 1916. He soon ran out of room and resorted to writing names up the sides and in any vacant space.

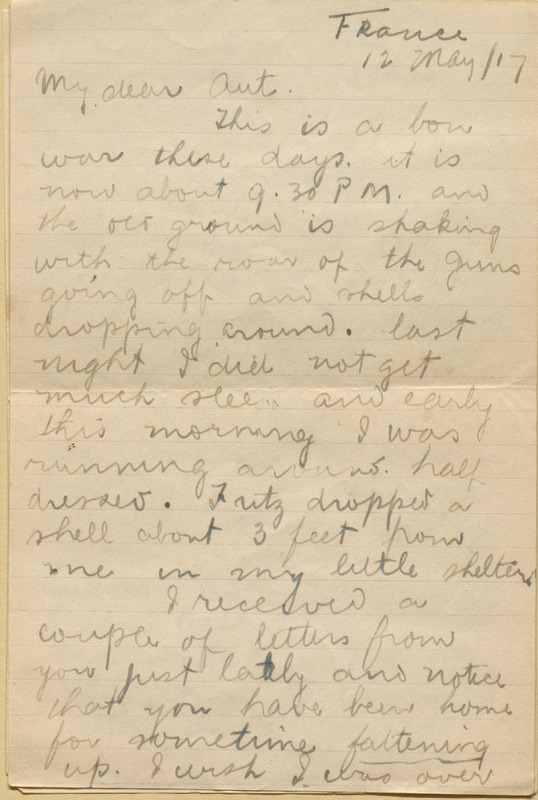

In 1917, Ingersoll born, Reginald Richardson (1891-) wrote to his sister from France about his day:

Our ground is shaking with the roar of the guns going off and shells dropping around. Last night I did not get much sleep and early this morning. I was running around half dressed Fritz dropped a shell about 3 feet from me in my little shelter.

It is easy to read these accounts solely through a lens of heroism, honour and sacrifice, but this hinders the knowledge that these were written by ordinary, everyday people who were living through great physical, emotional, and mental hardship. During the war, many terms were used to describe the mental effects of the war: shell shock, soldier's heart, battle fatigue. All these terms are now understood to describe the effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Very little material of the material around trauma was preserved as the understanding effects of trauma were far less developed. The physical effects associated of PTSD were also associated stigmas surrounding mental illness and associated with cowardice. Soldiers in the First World War, like Bateman or Richardson, did not tend to write how events made them feel, just that they happened. Accordingly, such material is difficult for institutions to collect, and more difficult still to draw attention to this significant issue which so many faced both during, and after the war. The Fisher library is fortunate to have several such examples, which provide unflinching and honest accounts of the effect the war had on Canadian soldiers and their families.

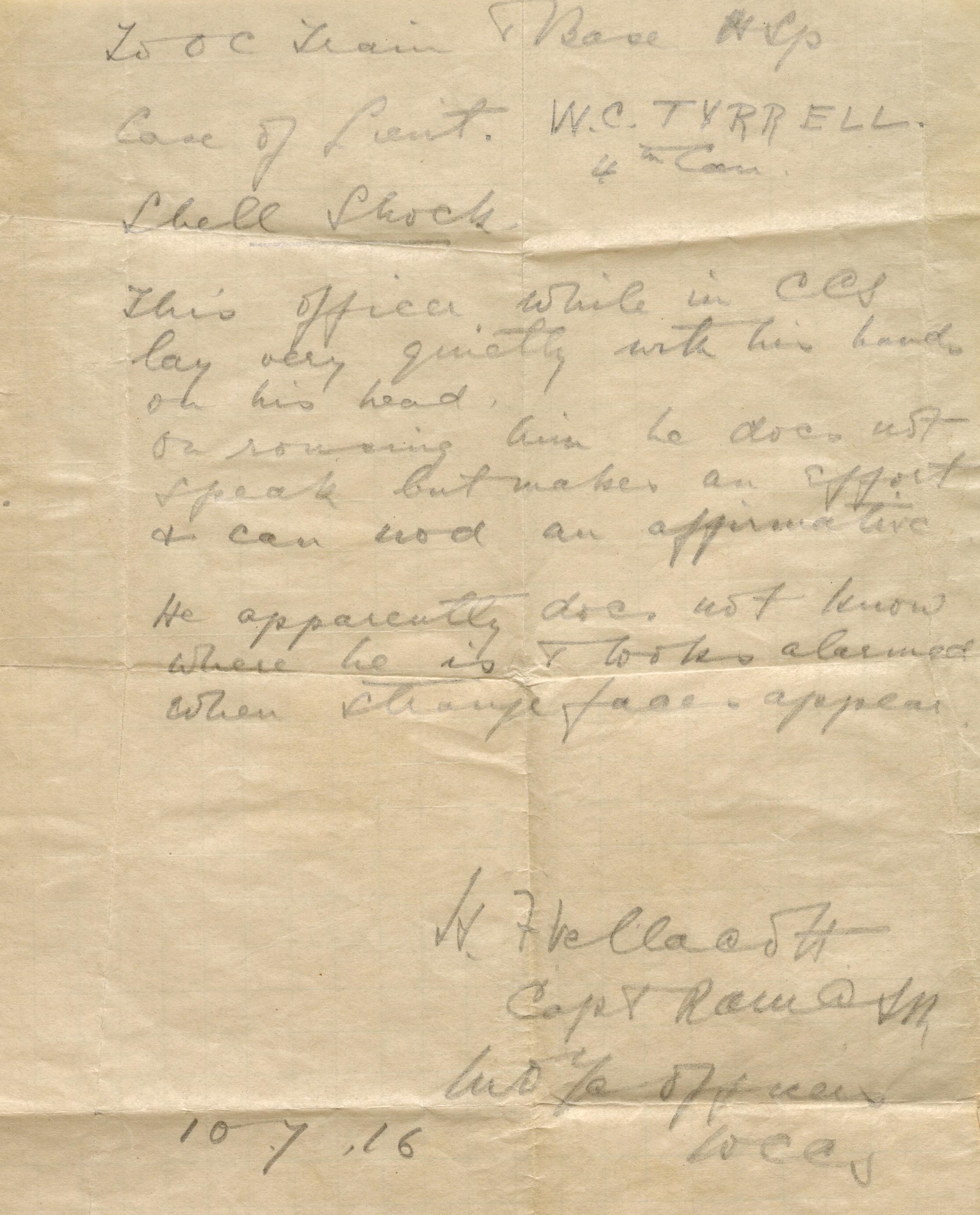

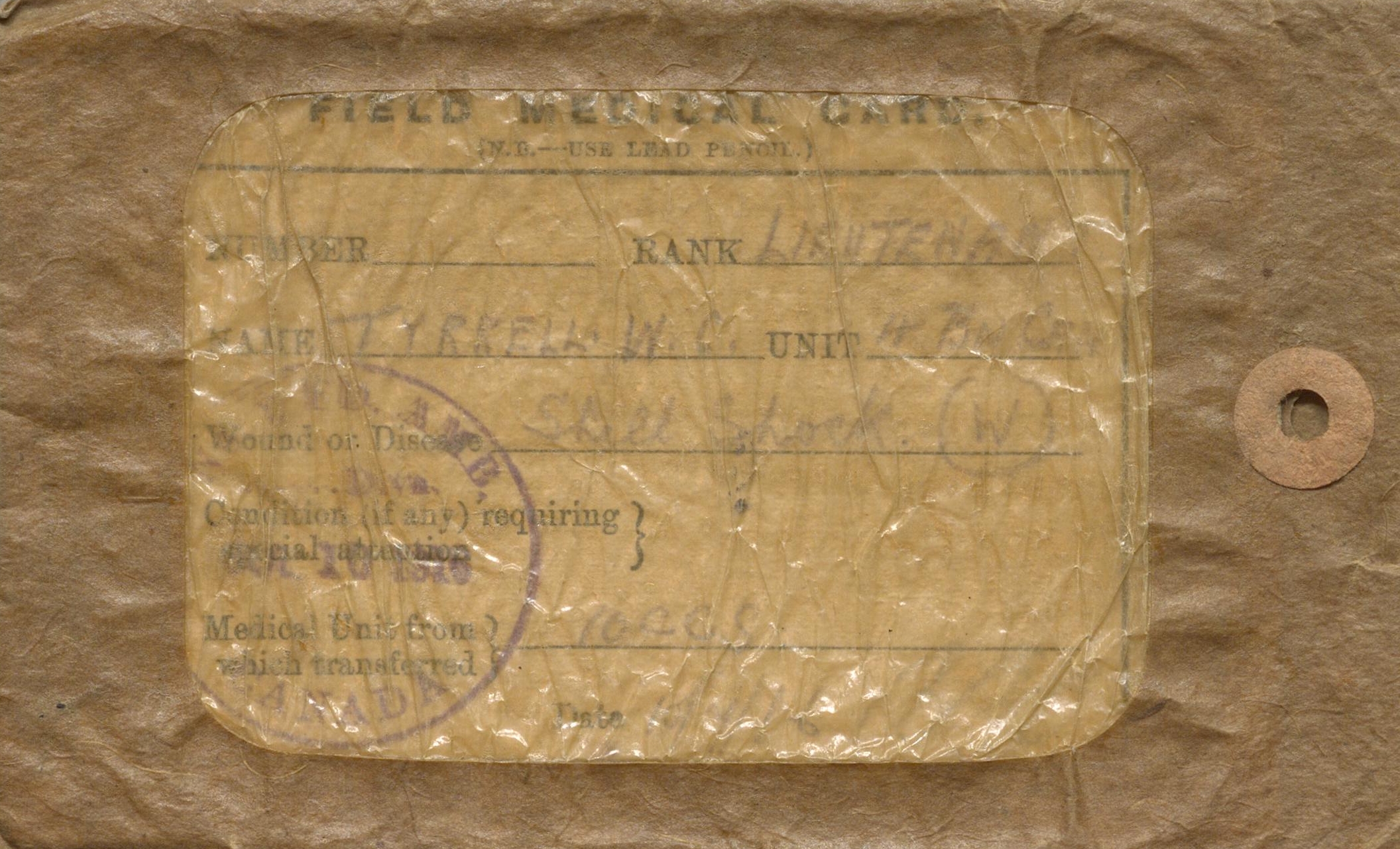

William Charlton Tyrrell (1892-1982) was a Lieutenant in the 4th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. His military record reveals that 10 July 1916, while fighting in the Battle of the Somme, Tyrrell was “buried on three different occasions during one afternoon” due to extensive shelling. He was retrieved, unconscious, after the third shelling and brought to a clearing station. Once he was revived, the doctor jotted out a quick note about his condition:

[Tyrell] lay very quietly with his hands on his head, on rousing him he does not speak but makes an effort + can nod an affirmative. He apparently does not know where he is + looks alarmed when strange faces appear.

This note, along with his field Medical Card declaring his wound as “shell shock” was pinned to Tyrell as he was evacuated to a hospital, and later to convalesce in Canada. Tyrell’s shell shock was so severe that he was permanently discharged.

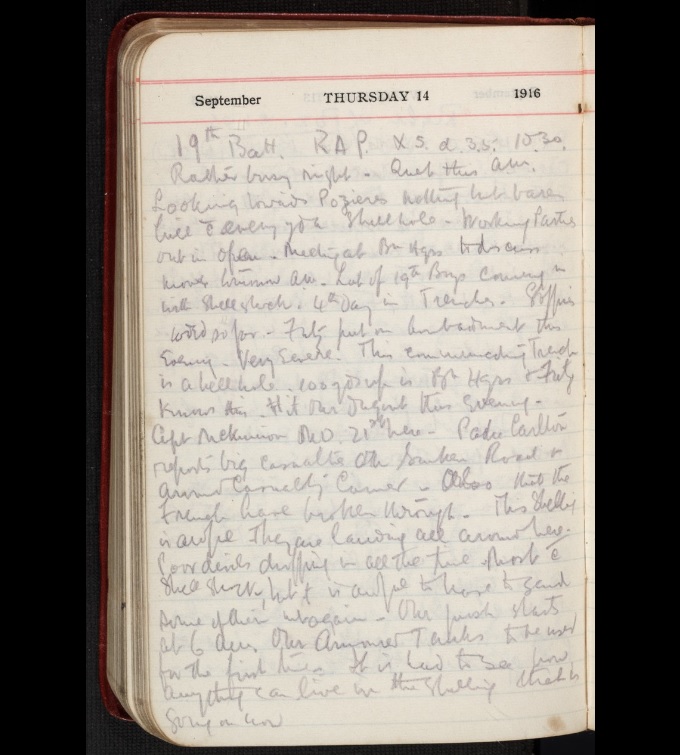

Ronald Hugh MacDonald (1885-1949) served as a doctor and surgeon in the Canadian Army Medical Corp from 1914 to 1918, and would spend just shy of three years working in hospitals and clearing stations in France. His diary, maintained between 1915 and 1918, reveals the terrible effect from both injury and disease, the war had upon the soldiers. One significant entry records one night on 14 September 1916, during the Battle of Courcelette.

Lot of 19th boys coming in with shell shock. 4th day in trenches. 8 officers wded so far. Fritz put on bombardment this evening. Very severe. This communications trench is a hell hole. 100 yds up is Bn Hqrs & Fritz knows this. Hit our dugout this evening. Capt McKinnon M.O. 21st here. Padre Carlton reports big casualties on Sunken Road & around Casualty Corner. Also that the French have broken through. This shelling is awful. They are landing all around here. Poor devils dropping in all the time most with shell shock, but it is awful to have to send some of them out again.

While Tyrrell and MacDonald’s documents show the immediate effect of trauma on the soldiers during the war. The repercussions of soldier’s trauma continued long after the celebration of Armistice Day were over.

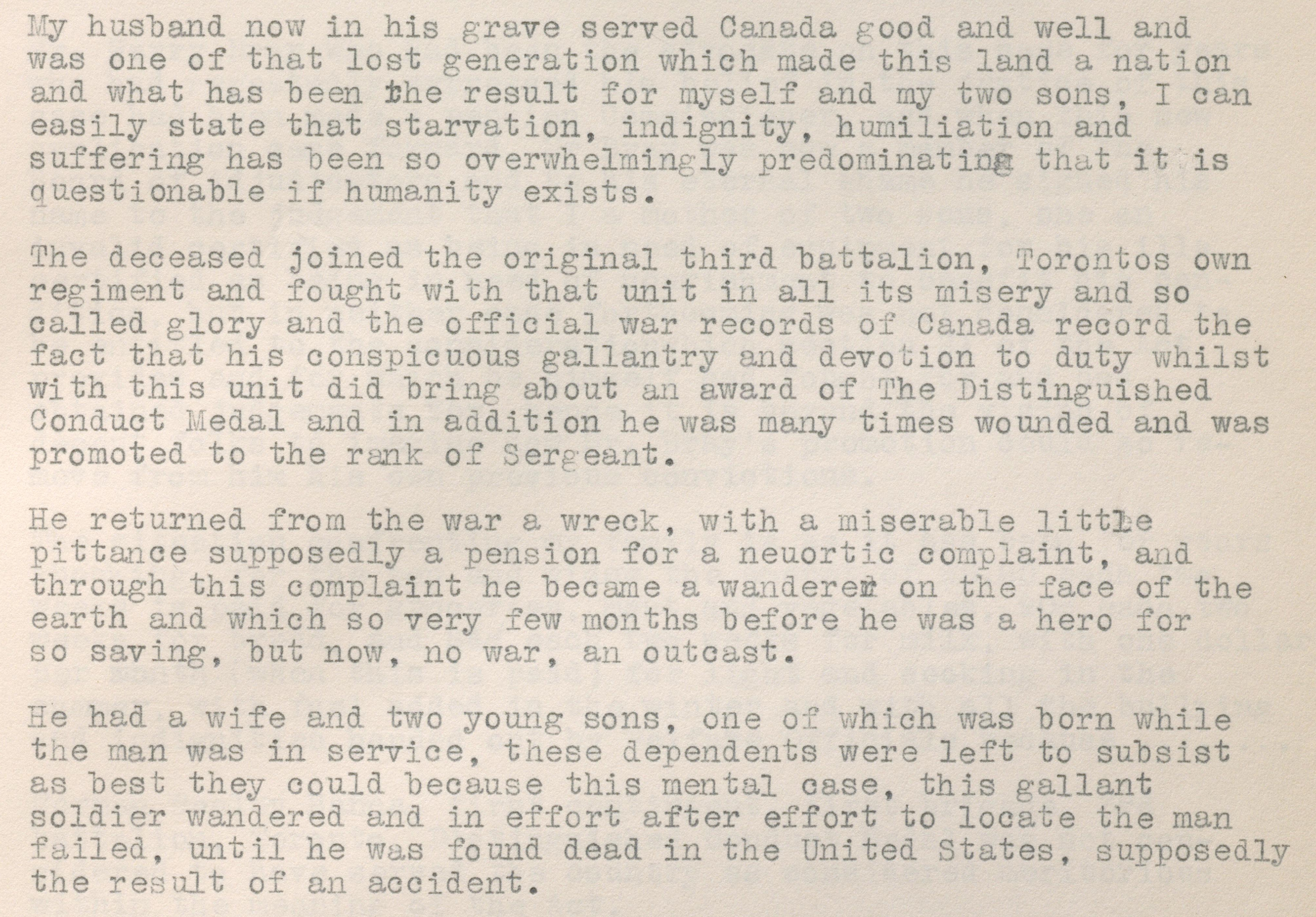

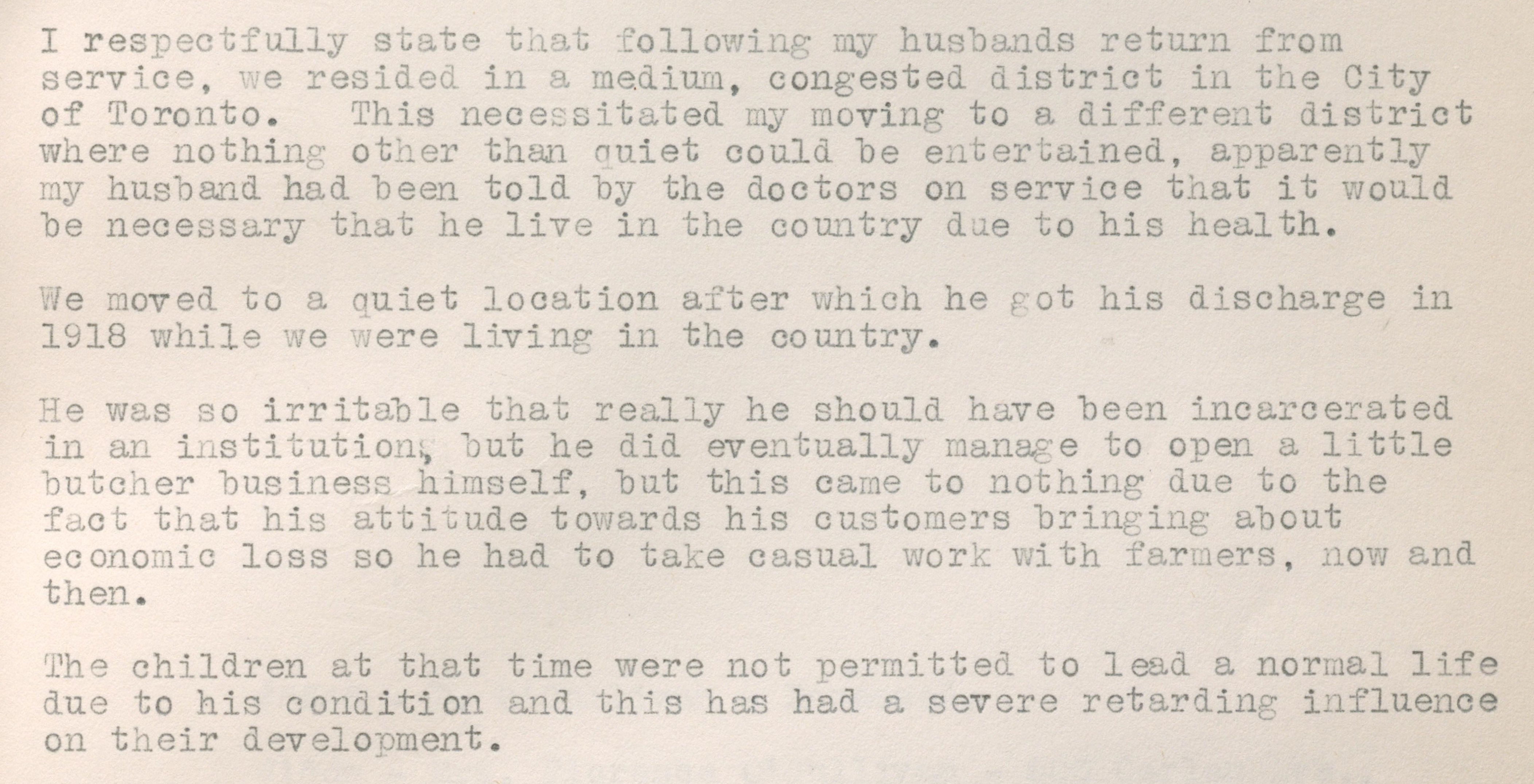

In 1941 - twenty-three years after the war had ended, and with a new war raging in Europe - the York Veteran's Social Welfare Club collected accounts of soldiers and widows, who had faced hardship directly attributed to the war. The resulting bound book, requesting greater pension support, was submitted to their local Member of Parliament to be brought to the attention of the Government of Canada. All written by residents of Toronto, the majority of the thirty-eight accounts are written by women whose husbands survived the war, but consequently died prematurely from war related medical conditions, including those related to mental health.

Of her now-deceased husband, Norman, Lillian Hanna recalled, "he returned from the war a wreck, with a miserable little pittance supposedly a pension for a neuorotic complaint, and through this complaint he became a wanderer on the face of the earth, and which so very few months before he was a hero for so saving, but now, no war, an outcast ... this gallant soldier wandered and effort after effort to locate the man failed, until he was found dead in the United States."

Mary Foster wrote of her deceased husband, "He cam[e] home in 1919 and could not follow any steady employment ... his health become of such that he became unbearable to live with and I was in continuous suspense not knowing which way to turn from day to day."

Mrs Ada Fryers' husband, Louis, died in 1939. She wrote, "Upon his return to civil life it was quite obvious that he was unwell ... for many years prior to his death my husband was unable to follow his employment and for seven years we were the recipients of relief with all its degradation and attendant degeneration, and the family were drawn down to that which might be termed dire poverty the only cause of which was their fathers service to the State."

Mrs James Lockrey reported that when her husband returned they had to leave Toronto as "nothing other than quiet could be entertained ... he was so irritable that really he should have been incarcerated in an institution ... from the lay point of view I am convinced he was not sane; he took violent fits of rage both at home and away, he couldn't enjoy any normal enjoyment as he would become so excited with the slightest movement out of the quiet that excitement would overcome him."

All together these scarce accounts provide a very real insight into the horrors of war and the trauma that stemmed from it, which demonstrating the suffering Canadian soldiers and nurses experienced during the war and in its aftermath. These perspectives are incredibly significant to preserve, discuss and remember as a part of the history of the First World War.

- Danielle Van Wagner, Special Collections Librarian