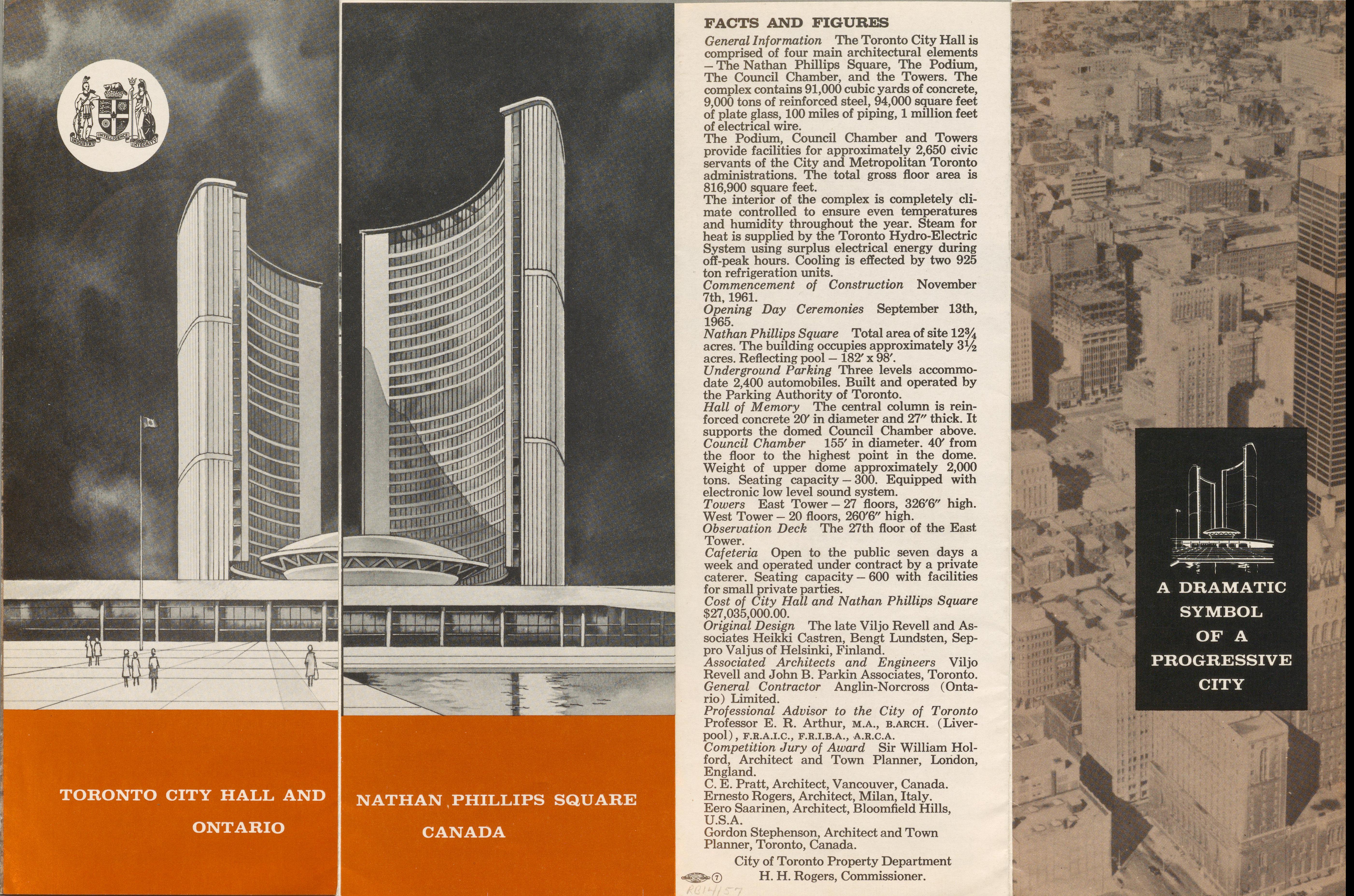

By the early 1950s Toronto had outgrown the formidable Romanesque-style city hall building at the corner of Queen and Bay streets, its home since 1899. The city’s projected space needs could not be accommodated within existing buildings, and so it was decided that a new city hall with a public plaza would be built. The new building had the potential to redefine the city’s landscape and heighten its international profile, and inevitably supporters of traditional and contemporary styles were at odds about what it should look like and who should design it. After initial proposals drafted by local architectural firms in a conventional style were rejected in 1955, Mayor Nathan Phillips was permitted to open an international competition to design the new city hall. Voters agreed on an eighteen million dollar budget for the building in 1956, and Eric Arthur, professor of architecture at the University of Toronto was chosen to act as professional advisor for the competition. A statement of conditions was drafted and architects and designers set themselves to imagining what Toronto’s new city hall should look like.

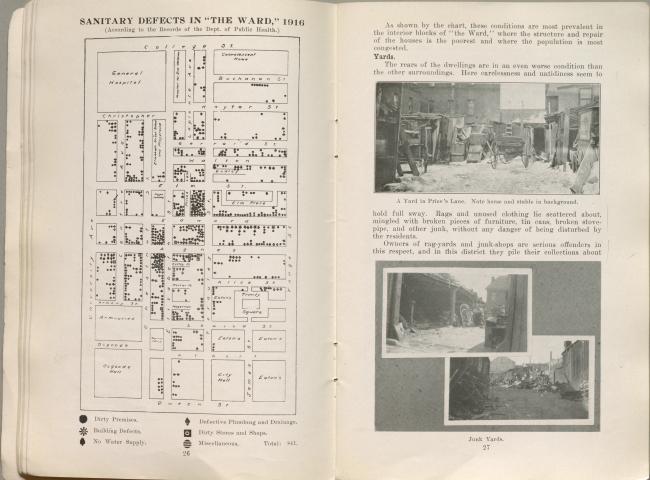

The land on which the new City Hall was to be built was not vacant, but occupied by the St. John’s Ward neighbourhood, home to many of Toronto’s recent immigrant communities, artists, and Toronto’s original Chinatown. A negative public impression of the ‘Ward’ neighbourhood and its living conditions combined with urban renewal plans in the late 1940s and the need for land for the new City Hall meant that despite protests, the neighbourhood, including two-thirds of Toronto’s original Chinatown was eventually expropriated and its residents displaced.

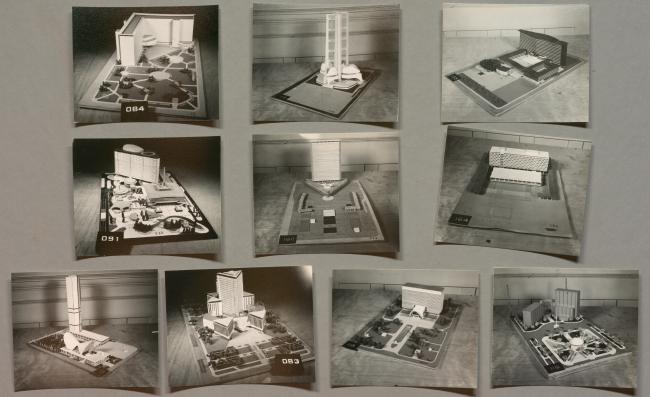

By the competition deadline at the end of 1957, over 500 models and designs had arrived from more than 40 different countries, to be narrowed down to eight finalists by Eric Arthur and a jury of internationally renowned architects. Models and plans were set up at the Canadian National Exhibition’s horticultural building for two weeks. Each jury member could express their approval or dismissal by leaving coloured squares on the model, and the group would debate their merits before deciding what to eliminate. The eight finalists were chosen in April of 1958 and were given five months and $7,500 in financial assistance to adjust and expand their proposals before the final judgement. The winner, Viljo Revell of Finland, was announced on the September 26, 1958.

After the competition, some of the architectural models went on public display at the Eaton’s store on Queen street west. During the process of mailing, judging, moving, and displaying, many of the fragile models sent in for the competition were damaged or destroyed but several photographic records of the entries exist. The photographs below held at the Fisher Library allow us to imagine what the core of our city might have looked like if a different design had been chosen as the winner.

[City Hall designs from top left: V. Maermans, Belgium; A. Bourbonnais, France; L. Rebands, J. Fielding, Canada; John Farrar, England; A. Remondet, Paris; Name not noted; D. Marshall, B. Adams, England; Alan Graham, Canada; local-no name; P. Branche, Paris.]

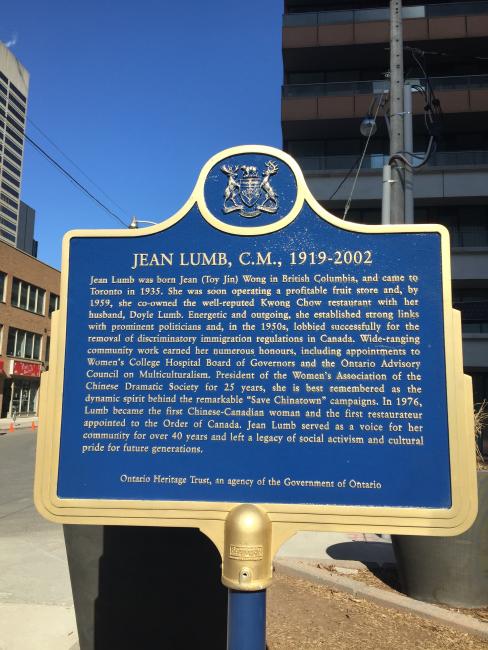

Many stages of the competition and redevelopment were troubled or contentious; although press coverage and public response to Revell's design were positive, it was not universally loved. Architect Eero Saarinen had rescued it from the jury's discard pile early on, and Mayor Phillips disliked the winning design. Viljo Revell passed away at 54, just three years into the eight-year long construction of the new City Hall. The city also had to deal with the long-term impact of losing a major downtown community, and the shifting and migration of many of its immigrants to the West and North. Some businesses from the original Chinatown moved West to Spadina, and those that remained were also part of later development proposals, but many were saved thanks to local community leader and entrepreneur Jean Lumb and her ‘Save Chinatown’ committee. Her impact is remembered with a heritage plaque very close to the current location of City Hall.

- Liz Ridolfo, Special Projects Librarian, Fisher Library

Sources

Armstrong, Christopher. Civic symbol: creating Toronto's new City Hall, 1952-1966 University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Dickau, J., Pilcher, J., & Young, S. (2021). If you wanted garlic, you had to go to Kensington: culinary infrastructure and immigrant entrepreneurship in Toronto’s food markets before official multiculturalism. Food, Culture, & Society, 1–18.

Vitiello, D., & Blickenderfer, Z. (2020). The planned destruction of Chinatowns in the United States and Canada since c.1900. Planning Perspectives, 35(1), 143–168.

The Ward : The Life and Loss of Toronto's First Immigrant Neighbourhood, edited by John Lorinc, et al., Coach House Books, 2015