A night out on the town in Toronto is ephemeral by its very nature. After the lights at a dance club come on, a restaurant closes its doors, or a dinner party breaks up, the event inevitably fades from memory and from the historical record. There is however more of a paper trail left over from social events of the past than may first appear, and the survival of menus, invitations, dance cards, visiting cards, and posters help to shed light on this aspect of Toronto’s history. The survival of these objects is often haphazard, some are deliberately saved as mementos whether on their own or pasted into scrapbooks and diaries, others make their way to the library stuffed into books as bookmarks, and in some rare cases there is a more systematic approach to their collection and preservation. Except for those placed inside books, these items are most often found in the library’s ephemera collection, scattered through archival collections, or catalogued on their own depending on their age and rarity. They are also at times included in discrete collections of material that the library has decided to keep together, such as 2 boxes of early Canadian menus donated in 2015 by Mary Williamson.

Their dispersal around the library also reflects the nature of ephemera, as these objects do not often easily fit into the library’s classification schemes. In the past ephemera did not receive much attention in special collections more generally but this has certainly changed in recent years. For its part, the Fisher Library has made finding aids for its ephemera collection searchable online and has increasingly sought to add unique and interesting pieces to this collection. (The full list of our ephemera collection can be accessed via this link.) This post will explore these items held at the Fisher library, how they were used, and how they survived to be included in the library’s collection.

Visiting cards

Often a prelude to a more formal invitation to an event, visiting cards are quite a foreign concept now, however from the mid 18th into the 20th centuries, the visiting card was an integral component in the social lives of the upper-middle and upper classes in Europe and North America. The system of leaving visiting cards involved an intricate set of social conventions that both established the class of the sender while conveying a variety of meanings to the recipient of such a card, which was deposited most often on a tray by the front door. A turned down corner indicated that the card was delivered in person, rather than by a servant. A corresponding card sent by the recipient could indicate that a visit or invitation to dine would be welcome, however if such a card were delivered in an envelope it meant that such a visit was kindly discouraged. The accepted design and use of these cards changed throughout the years and sometimes even from social season to social season and the person who either failed to take notice, or willfully deviated from the accepted norms could be considered lacking in good taste or manners. An example of this can be seen in an article in the Christian Inquirer from April 12, 1856 which discourages the enamelling of cards saying, "a shiny card imparts no lustre on the name upon it; but communicates an appearance of vulgar glitter to the table or shelf whereupon it is deposited." Reading etiquette manuals’ discussions of visiting cards lead one to think of Edith Wharton’s novel about New York high society “The Age of Innocence,” where individuality that deviated from accepted norms and conventions are met with derision and social disaster. Thus, most visiting cards are rather restrained, with simply a person’s name and title.

Often a prelude to a more formal invitation to an event, visiting cards are quite a foreign concept now, however from the mid 18th into the 20th centuries, the visiting card was an integral component in the social lives of the upper-middle and upper classes in Europe and North America. The system of leaving visiting cards involved an intricate set of social conventions that both established the class of the sender while conveying a variety of meanings to the recipient of such a card, which was deposited most often on a tray by the front door. A turned down corner indicated that the card was delivered in person, rather than by a servant. A corresponding card sent by the recipient could indicate that a visit or invitation to dine would be welcome, however if such a card were delivered in an envelope it meant that such a visit was kindly discouraged. The accepted design and use of these cards changed throughout the years and sometimes even from social season to social season and the person who either failed to take notice, or willfully deviated from the accepted norms could be considered lacking in good taste or manners. An example of this can be seen in an article in the Christian Inquirer from April 12, 1856 which discourages the enamelling of cards saying, "a shiny card imparts no lustre on the name upon it; but communicates an appearance of vulgar glitter to the table or shelf whereupon it is deposited." Reading etiquette manuals’ discussions of visiting cards lead one to think of Edith Wharton’s novel about New York high society “The Age of Innocence,” where individuality that deviated from accepted norms and conventions are met with derision and social disaster. Thus, most visiting cards are rather restrained, with simply a person’s name and title.

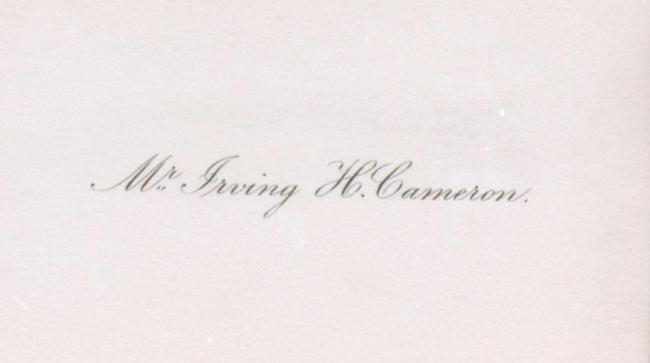

The visiting card, although perhaps most rigorously used in places where concentrations of wealth and title existed, such as London or New York, was also used amongst a certain class of people in Toronto. An example can be seen here of the card of Irving H. Cameron (1855-1933), a Toronto physician who was the President of the Canadian Medical Association and Chief Surgeon at the Toronto General Hospital. This card was preserved by being stuck into a book, either as a bookmark, or possibly to indicate who the book was being presented by.

Invitations

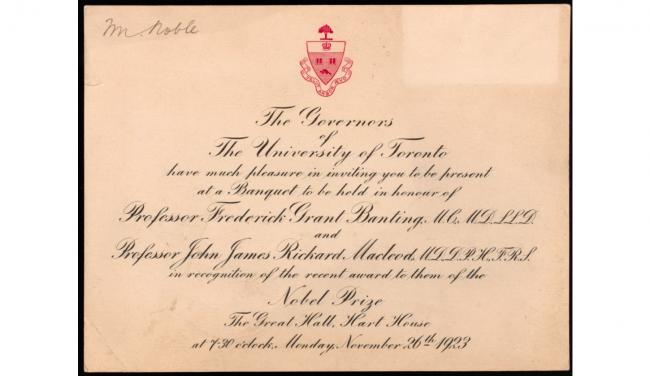

Written invitations, although perhaps now most common for weddings, have been used for centuries, and are often the only paper record of an event having taken place. Formal or informal, elaborate or plain, the Fisher Library has countless examples of invitations and due to our location and that of many of our donors, many of those in the collection come from events that have been held in the city. Like visiting cards, their survival can be by chance, but more often what is preserved are invitations to particularly noteworthy events that were kept as souvenirs. One such example can be seen here of an invitation on behalf of the Governors of the University of Toronto to a banquet celebrating Frederick Banting and J. J. R. McLeod on their Noble Prize in 1923. This invitation is held in the Academy of Medicine Collection and the name at the top corner, Mr. Nobel, suggests it was most likely given to Dr. R. T. Noble, then president of the Toronto Academy of Medicine.

Written invitations, although perhaps now most common for weddings, have been used for centuries, and are often the only paper record of an event having taken place. Formal or informal, elaborate or plain, the Fisher Library has countless examples of invitations and due to our location and that of many of our donors, many of those in the collection come from events that have been held in the city. Like visiting cards, their survival can be by chance, but more often what is preserved are invitations to particularly noteworthy events that were kept as souvenirs. One such example can be seen here of an invitation on behalf of the Governors of the University of Toronto to a banquet celebrating Frederick Banting and J. J. R. McLeod on their Noble Prize in 1923. This invitation is held in the Academy of Medicine Collection and the name at the top corner, Mr. Nobel, suggests it was most likely given to Dr. R. T. Noble, then president of the Toronto Academy of Medicine.

Menus

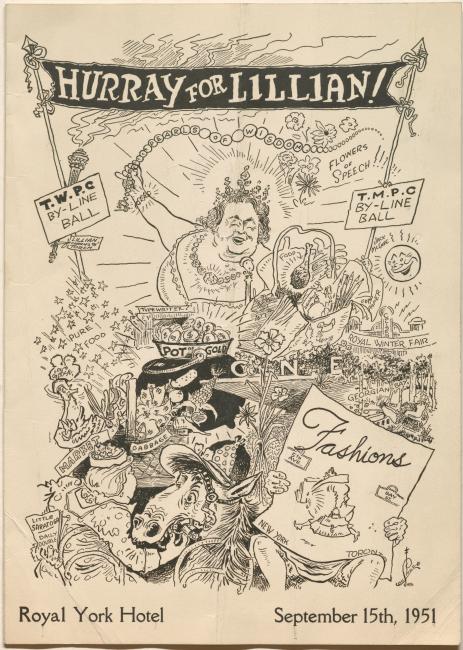

Another common item that survives from past events is menus, whether on their own or included as part of a program. Fisher holds many menus, a good portion of which are from Toronto. The design of a menu and the items served often provide clues to the tone of the event itself. It’s not clear from this menu and program what Lillian was being celebrated for, but if the menu is any indication, the event was a boisterous one. The cover includes an illustration, or caricature, of what is presumably the titular Lillian, holding a strand of "pearls of wisdom," with a wild mix of images and phrases below her. Each course except for dessert included alcohol as an ingredient and it was held at the fashionable Royal York Hotel.

Another common item that survives from past events is menus, whether on their own or included as part of a program. Fisher holds many menus, a good portion of which are from Toronto. The design of a menu and the items served often provide clues to the tone of the event itself. It’s not clear from this menu and program what Lillian was being celebrated for, but if the menu is any indication, the event was a boisterous one. The cover includes an illustration, or caricature, of what is presumably the titular Lillian, holding a strand of "pearls of wisdom," with a wild mix of images and phrases below her. Each course except for dessert included alcohol as an ingredient and it was held at the fashionable Royal York Hotel.

Dance cards

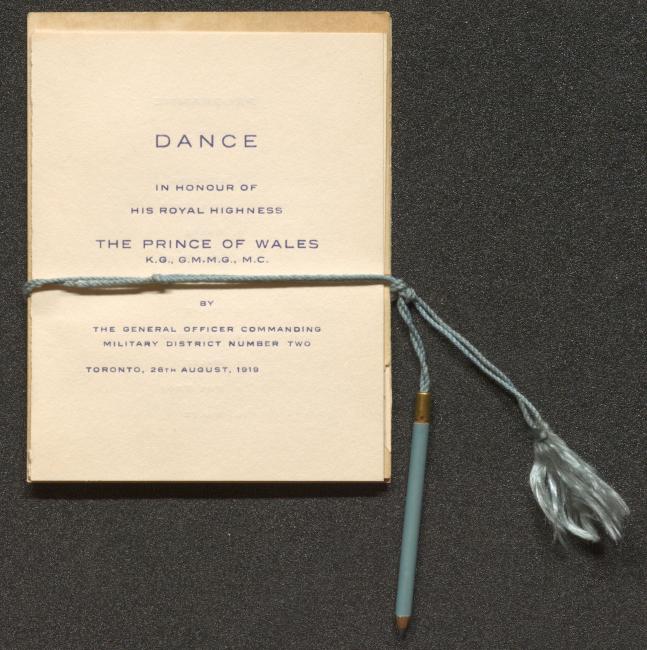

The origin of the phrases "let me pencil you in" or "my dance card is full," a dance card is a small booklet, usually meant to be attached to the wrist, by which women organized their evening at a formal ball or dance. Given out at the beginning of the event, when a man asked a woman to dance, she would write his name into her book so as not to forget who had “booked” her for a particular dance. It was much less common for a man to be given a dance card, with the expectation that he remember which lady he was meant to dance with at a given point. These books often list the type of dance and sometimes the name of the composer with a blank line next to them to fill in. Dance cards became popular in the 19th century and were used well into the 20th century. Like visiting cards there were points of etiquette and rules governing their use. If a lady were accompanied by an escort, he would often indicate his name on her card with an XX next to a dance. It was also considered inappropriate to give over too many dances to a particular gentleman, to give all potential suitors a chance. There was also the eternal debate of “where to keep the pencil” that usually came with dance cards, as ladies’ dresses generally did not have pockets and one had to carry it around all night. It therefor became polite for men to carry their own pencils to make it less awkward.

The origin of the phrases "let me pencil you in" or "my dance card is full," a dance card is a small booklet, usually meant to be attached to the wrist, by which women organized their evening at a formal ball or dance. Given out at the beginning of the event, when a man asked a woman to dance, she would write his name into her book so as not to forget who had “booked” her for a particular dance. It was much less common for a man to be given a dance card, with the expectation that he remember which lady he was meant to dance with at a given point. These books often list the type of dance and sometimes the name of the composer with a blank line next to them to fill in. Dance cards became popular in the 19th century and were used well into the 20th century. Like visiting cards there were points of etiquette and rules governing their use. If a lady were accompanied by an escort, he would often indicate his name on her card with an XX next to a dance. It was also considered inappropriate to give over too many dances to a particular gentleman, to give all potential suitors a chance. There was also the eternal debate of “where to keep the pencil” that usually came with dance cards, as ladies’ dresses generally did not have pockets and one had to carry it around all night. It therefor became polite for men to carry their own pencils to make it less awkward.

Dance cards are not uncommon but as with much ephemera do have a fairly low survival rate, with examples generally only surviving if they were kept as souvenirs. Seen here is one of the unusual examples of a dance card given to a man. It is from a dance given in honour of the Prince of Wales as part of his royal tour, on Aug. 26, 1919 in Toronto, and as it turns out, this bachelor was indeed "fully booked."

Posters

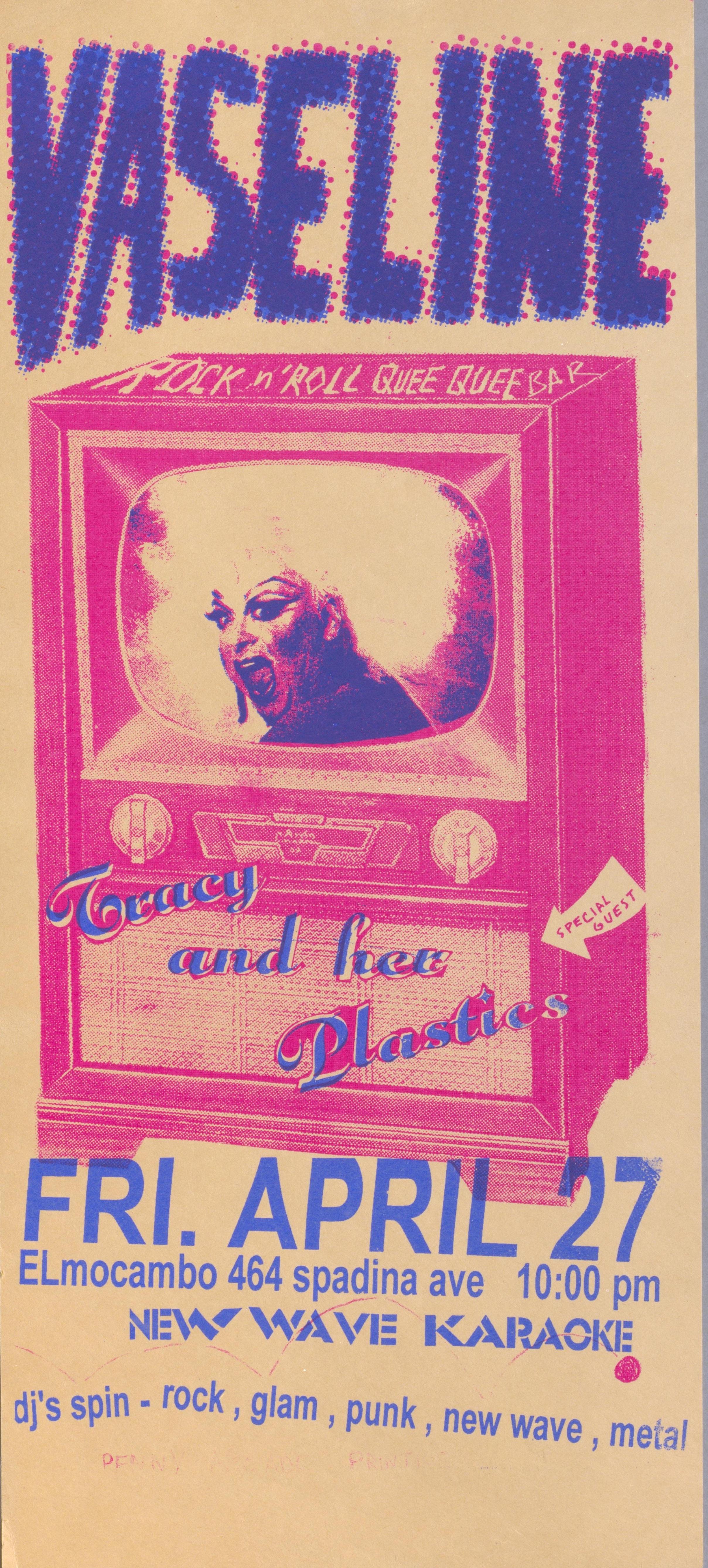

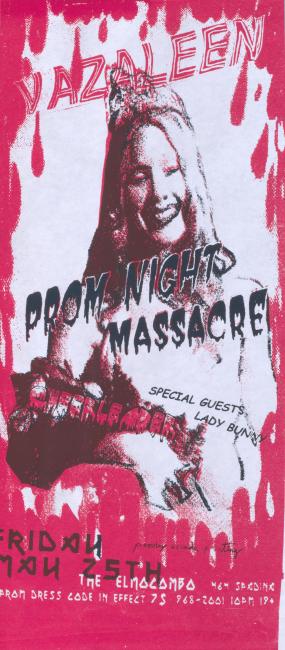

Posters advertising events surviving in good condition are somewhat unusual due to their very nature. Exposed to the elements, taped and tacked to boards, and generally pasted over or ripped off once obsolete, posters are part of the Toronto landscape, but the proportion of them that are preserved for longevity is very small. That said, there are some exceptions, and one of those is Fisher’s collection of Vazaleen posters. Originally called Vaseline, Vazaleen was a monthly queer party that operated from 1999 to 2006 and was held at iconic Toronto venues like El Mocambo and Lee’s Palace. It was conceived by artist and party promoter Will Munro (1975-2010) as an event designed to be welcoming to a more alternative and diverse crowd than the mainstream Village club scene. The event was exuberant and featured many activities that are perhaps too racy to discuss in a library blog. It also helped launch the careers of Peaches and Crystal Castles. The party continues with Vazaleen being an annual feature of Pride Week, raising money for the Will Munro Fund for Queer and Trans People Living with Cancer.

Posters advertising events surviving in good condition are somewhat unusual due to their very nature. Exposed to the elements, taped and tacked to boards, and generally pasted over or ripped off once obsolete, posters are part of the Toronto landscape, but the proportion of them that are preserved for longevity is very small. That said, there are some exceptions, and one of those is Fisher’s collection of Vazaleen posters. Originally called Vaseline, Vazaleen was a monthly queer party that operated from 1999 to 2006 and was held at iconic Toronto venues like El Mocambo and Lee’s Palace. It was conceived by artist and party promoter Will Munro (1975-2010) as an event designed to be welcoming to a more alternative and diverse crowd than the mainstream Village club scene. The event was exuberant and featured many activities that are perhaps too racy to discuss in a library blog. It also helped launch the careers of Peaches and Crystal Castles. The party continues with Vazaleen being an annual feature of Pride Week, raising money for the Will Munro Fund for Queer and Trans People Living with Cancer.

The posters were a striking addition to street poles around the city and caught the eye of donor Don McLeod who later came across the artist, Michael Comeau, selling some of the posters at an event at the Gladstone Hotel in the early 2000s. McLeod arranged with Comeau to purchase a copy of each poster he created thereafter. This is how Fisher has come to hold 71 posters in pristine condition from this iconic Toronto event.

- Andrew Stewart, Reading Room Supervisor, Fisher Library

Bibliography:

Punch. Etiquette of Visiting Cards. Christian Inquirer, 10 (28), April 12, 1856), page 4.