Zines (derived from the term “fanzines” or “fan-magazines) are a fluid literary creature. In a very broad yet clear explanation, Stephen Duncombe notes that “zines are non-commercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their creators produce, publish, and distribute themselves”—although, this does not encompass all items that fall under the umbrella of ‘zine.’ Zines are most often associated with the unpolished photocopied A4 folded/stapled piece of paper, but the historical and current iterations of zines can be found in all shapes and sizes. The origin of this genre is widely regarded to begin in the 1930s with the advent of science fiction fanzines, though some scholars have argued that even earlier version can be found. Following the invention and distribution of technology such as the mimeograph, xerox machine and IBM typewriters, the scale of creation and distribution for self-published non-commercial works fueled a relatively rapid increase in this subcultural genre. Following this, the 1970s punk zine explosion, and the 1990s girlzine revolution are major historical movements within the zine world.

The 1970s were a time of great political unrest in Britain, which dovetailed with the punk music scene taking a stronghold. In response, people such as Mark Perry (creator of Sniffin’ Glue, which is widely recognized as the first British punk zine) began creating zines that functioned as “cultural mouthpieces for punk bands-- fanzines disseminated information about gig schedules, interviews with bands and reviews of new albums alongside features on current political events and personal rants.” The “do-it-yourself” nature of the zines themselves, which were (and still are) hand folded, scrappy collages of images and text, reflected the punk movement and the political rallying cries of bands such as the Sex Pistols, The Ramones, Adam & the Ants and many more. The central focus of punk music, and thus the fanzines that were borne out this era highlight the notion of resistance and the rejection of mainstream culture, politics, and opinions.

Carrying on the tradition of DIY and resistance to the mainstream, members of Riot Grrrl punk band Bikini Kill began to write and create their own zines in the early 1990s. Though, their motivations were slightly different from that of the 1970s punks zine creators, in that the ‘girlzine’ scene (as it became known) was fundamentally about carving out a space for women and girls to discuss feminism, but also “the multiple ways they were dismissed, scorned, violated, and controlled not only in the punk scene but also in their daily lives.” The late 1990s onward also saw the advent of e-zines, or digitally created and distributed zines, which broadened the look of what was typically associated with the zine genre. Zines, at their core, can take on any subject and look however the author pleases—the only limitations are imagination and what materials are at their disposal. Though the DIY style of a folded piece of A4 paper is the most iconic iteration of the zine, the genre of zine is boundless.

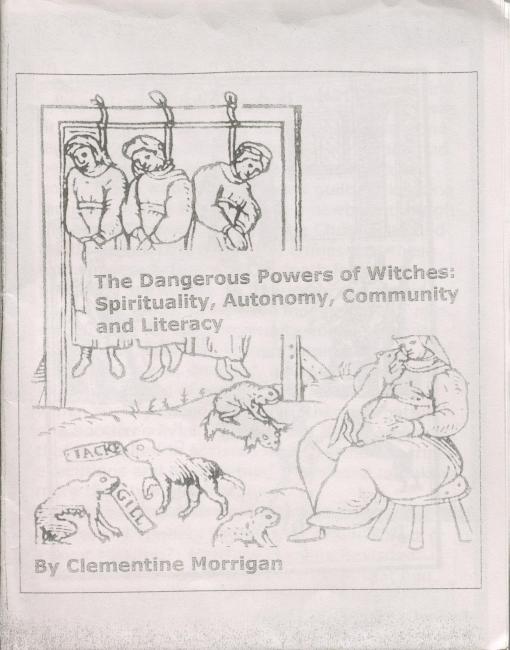

Morrigan, Clementine.The Dangerous Powers of Witches: Spirituality, Autonomy, Community and Literacy. Toronto, 2015.

Morrigan’s zine, which focuses on the persecution of women in the Middle Ages who were deemed ‘witches,’ falls under the category of the DIY zines of the 1970s and 1990s. According to its catalogue notes, the zine measures 14 cm, and contains 24 unnumbered pages that have been stapled together. In terms of its format, the zine has six double-sided pages folded length wise and then width wise to create 24 smaller pages. The Toronto Zine Library also notes that Morrigan’s work is categorized as a "lit zine," which is a term used for zines that highlight literature more than images or other visual materials, and may include content such as fiction, interviews, poems, essays and much more. This black and white zine has clearly been photocopied, giving it a slightly grainy quality to the pages. This appearance visually links Morrigan’s piece to the body of zine works that foreground the ‘undone’ DIY style of underground self-published items. It is clear that the artist used the cut and paste method to assemble the various paragraphs and images on each page, which were subsequently scanned to create a merged document. Interestingly, the writing style within the zine feels quite academic and polished because of its in-text citations, works cited page, formal paragraph structure, and analysis on the power dynamics of men and women during the Middle Ages. This is contrasted with the zine format, which looks homemade, somewhat fragile because of the paper utilized, and intentionally simple in its design. The format and materials give it a temporary feel, because of how easily the zine could be damaged or lost. Ultimately, this style of zine creation works in tandem with Morrigan’s analysis about women and their engagement with counterculture. In the final lines of the zine Morrigan affirms that “we need to form community, reach out to the marginalized, provide education…and practice our spirituality as we see fit.” This zine communicates that though a message may be one of resistance, there is still a way to make that voice heard.

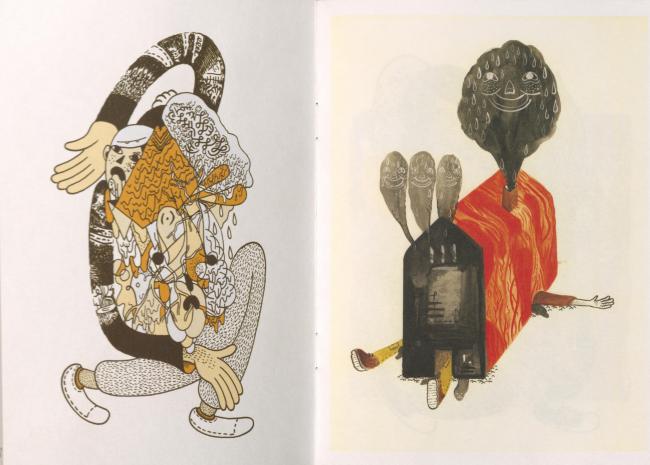

Williams, Justin B. and Luke Ramsey. A Great Big Stillness. Island Fold, 2006.

This zine, which is a collaboration between two visual artists in British Columbia, takes quite a different visual approach than Morrigan’s zine. A Great Big Stillness falls under the subgenre of art zines because it is entirely illustrations. Measuring 18 cm, it is taller than some styles of zines. The richly coloured illustrations and sturdy paper indicate that this is a more ‘professional’ version of a zine. The term ‘professional’ is contentious, but here, it draws attention to a level of embellishment and polish that is either not needed or avoided by other zine creators. The 20 pages of this zine are formatted with crisp borders around images, with no traces of photocopy grain, folding lines or hand-assembled qualities. The final page of the zine includes information about the publisher, and ISBN number, and a note about the location of the printing. This is quite unusual given that the majority of zines are created by individuals with no attachment to a company and no intention of being formally circulated or sold. Though some zines are created digitally, it is clear that A Great Big Stillness has the visual precision of high-quality digital programs and printing equipment. This zine was technically not self-published (though Ramsey, one of the creators, is a partial owner of Island Folds) or informally distributed in the ways that many zines are, which may cause some in the zine world to question whether this should be called a zine. However, as the genre has evolved, it has offered the opportunity for many artists, writers, and creators to share in the power of zines. Although zine may be a contested category, Williams and Ramsey’s work is part of an expanding tradition, which has no set definition. Simply put, their visual storytelling of a character interacting with a jumbled and disorienting environment, in the format of a compact and polished zine is a different but viable variant of the commonly known zine format.

- Percy Miller, Graduate Student, Faculty of Information

Bibliography

Blandy, Doug. “Zines Timeline compiled by Doug Blandy,” In Defense of the Realm: An Online Zine, Accessed Nov. 20, 2020. http://defenseof.voelkermorris.com/zine_time.html.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Portland (Microcosm Publishing, 2008), 10-11.

Morrigan, Clementine. The Dangerous Powers of Witches: Spirituality, Autonomy, Community. Toronto, 2015.

Radway, Janice. "Girl Zine Networks, Underground Itineraries, and Riot Grrrl History: Making Sense of the Struggle for New Social Forms in the 1990s and Beyond," Journal of American Studies 50, no. 1 (2016), 1-31. doi:10.1017/S0021875815002625.http://resolver.scholarsportal.info/resolve/00218758/v50i0001/1_gznuiafit1ab.

Toronto Zine Library, “All the Zines: The November Update,” Toronto Zine Library, Nov. 25, 2020. https://www.torontozinelibrary.org/?p=735.

Triggs, Teal. "Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic," Journal of Design History 19, no. 1 (2006), 69-83. http://www.jstor.org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/stable/3838674.

University of Toronto Libraries, “Catalogue Entry for A Great Big Stillness,” University of Toronto Libraries, Accessed Nov. 10, 2020. https://search.library.utoronto.ca/details?10286556