This week has been Freedom to Read Week, an annual event that is embraced by libraries and librarians across the country. There is no better environment than a library to celebrate the freedom to indulge in one's intellectual curiosity - in that regard, we like to think every week is freedom to read week. But given that books have become a target in the various cultural wars, it's a timely moment to reflect on how those freedoms shouldn't necessarily be taken for granted.

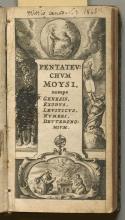

Here at Fisher, we've often celebrated Freedom to Read Week: we've visited high school libraries to talk about censorship, displayed challenged materials, and worked with students on creating exhibitions on the history of banned books. When teaching, we've brought items that have been censored: from the almost-comical (an inked out Adam and Eve on the title page of a small bible, see below) to the disturbing (the removal of any reference to Czechoslovakia in a textbook censored by the Nazis during the Second World War).

One of the great examples of attempted censorship at the Fisher is a 1541 publication of the Adagiorum of Erasmus, donated by Ralph Stanton. It was a source of much amusement when it was being catalogued about a decade ago by the department's former head PJ Carefoote.

As PJ wrote on the book, he was was impressed by the vigour with which it was censored, probably in the latter part of the 16th century:

"So earnest was the censor that at one point he actually removed pages, glued the remaining leaves together, and expunged the text with black ink, all in the same place. Erasmus, of course, was one of the great infants terribles of late medieval Catholicism, and as early as 1520, scholars were complaining that his adages were little more than a thinly veiled apologetic for the emerging Protestant movement. In 1541, all of Erasmus’s books were forbidden by the Sorbonne, and in 1559 they were incorporated into the universal Roman Index of forbidden books. It may have been the anonymous censor himself who added this Latin inscription (see detail below), in his own hand, to the title page of the Stanton copy, summarizing his opinion of Erasmus and his efforts: 'O Erasmus, you were the first to write the praise of folly, indicating the foolishness of your own nature.'"