Though the Fisher is known for its Shakespeare and other special collections, the library and University of Toronto Archives are full of many other treasures not typically seen, some of which are directly related to the building and its history. Often it is this kind of material that visitors find most interesting during our annual Doors Open Toronto open houses.

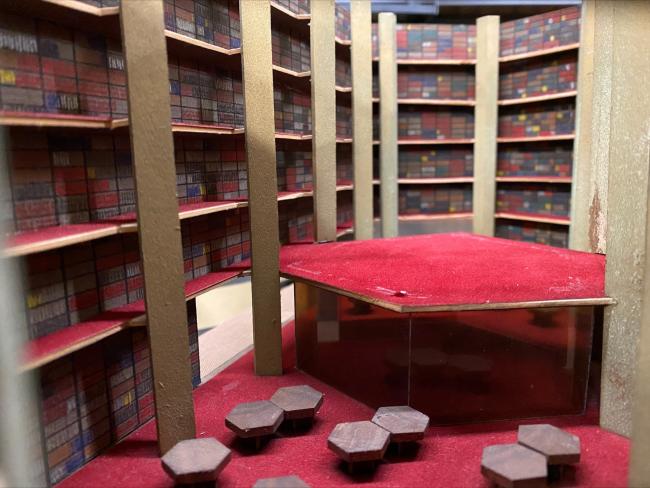

Some years ago, in a remote corner of the basement, a case was discovered, containing a wooden architectural model of the reading room, exhibition area, and stacks of the Fisher Library! Housed in a custom case, it came without paperwork or accompanying information. The architectural model focuses on the interior of the library, showing carpet colour, table colour and shape, and the stacks are painted to look as though they are full of books.

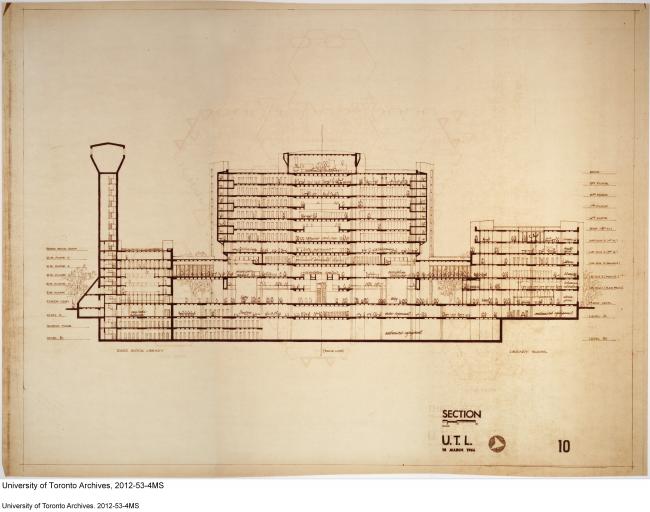

A cut out on the side and at the top give rare perspectives into the building, and the design is mostly unchanged from the model, though the model appears to be missing the glass panels of the exhibition area. This is somewhat different from the earlier architectural drawing of Robarts and Fisher (see below), which sees the Fisher with one fewer floor, and maintaining a free connection with Robarts through the periodical reading room (later the reference department).

Credit: University of Toronto Archives

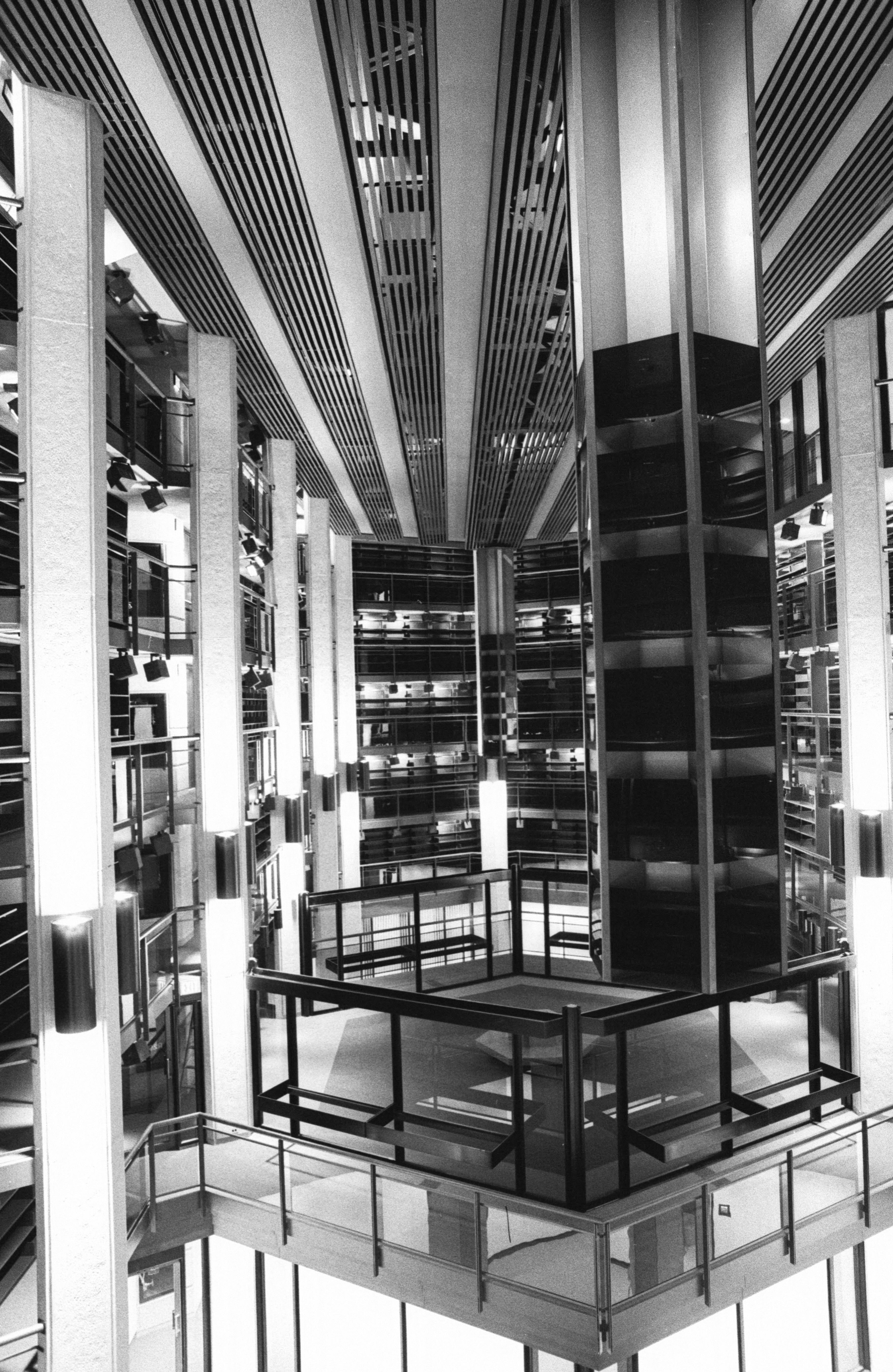

Though both share the same brutalist skeleton, the open layout and expansive height of Fisher’s mezzanines as well as its low lighting make it a warm space that gives a very different impression from some of the interior spaces of Robarts library, where the expansive concrete walls and ceilings are brightly lit and clearly visible.

Excavation for the library, which was designed by Mathers and Haldenby Architects with consultation from Warner, Burns, Toan & Lunde, began in November of 1968, and the 1,035,928 square foot building was completed four years and nine months later at a reported cost of 42 million dollars. The Fisher moved its collections to the new library and opened in December, 1972, while the official opening of the Robarts complex was in July 1973.

Part of the University’s original plan for Robarts intended it as a library restricted to graduate and upper year undergraduates only, and students protested this decision with an ‘Open the Stacks’ campaign, including a sit-in by protesters at the Senate Chamber on the second floor of Simcoe Hall on March 11, 1972.

Credit: University of Toronto Archives, Robert Lansdale, photographer.

Plans for the library’s design also came under scrutiny. Canadian Architect Magazine devoted a significant portion of its August 1974 issue to a series of protests and complaints about the new building. Managing editor Robert Gretton noted that many Toronto architects ‘voiced strong protests that such a monumental, inhuman building had been selected,’ stating that, though competent and well-intentioned, its New York architects had an 'apparent lack of sensitivity to the temper and pace of those who live and learn on the Toronto Campus.'

Compared to the '“enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete” that was the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s 1984,' the building was said to offend every sense, resembling 'not so much a place of learning as a World War II gun emplacement. Instead of a warm, humane space for the pursuit of studies, the library is a cold storage unit for paper and print.'

Ron Thom in his article of protest went so far as to call the building an 'illustrated dictionary of architectural miseries which are so blatant and so endless they approach the absurd.'

There were also critiques in the issue of the library’s initial interior layout and design, citing confusing arrangement and signage and a lack of foresight as far as technological growth potential in the building’s infrastructure.

Despite these initial protests, the library has served the needs of students well in past decades, with many upgrades and renovations of space, and in 1997 Robarts library received acknowledgement in the form of Grade B heritage protection as a good example of brutalism. Though the Fisher is not directly mentioned in these critiques, fans of our romantic interior and the Fisher Shakespeare collection might enjoy the image conjured up by Robert Gretton’s dramatic assertion in Canadian Architect that any reader doubting his feelings about the building should 'stand in the Rare Book Library at midnight. On a wintry night he may catch a glimpse of a distraught Lady Macbeth, with taper in hand, wailing “What’s done, cannot be undone.'’’

- Liz Ridolfo, Special Collections Projects Librarian

Credit: Black and white image of the Fisher's interior above are courtesy of the University of Toronto Archives, photographed by Robert Lansdale.

Sources:

University of Toronto Libraries at 125 https://exhibits.library.utoronto.ca/exhibits/show/utl125.

Concrete Toronto : a guidebook to concrete architecture from the fifties to the seventies. Michael McClelland and Graeme Stewart. Toronto: Coach House Books, c. 2007.

John P. Robarts Research Library, University of Toronto. Robert Gretton. The Canadian Architect (Archive: 1955-2005); Don Mills Vol. 19, Iss. 8, (Aug 1, 1974): 28-33.

Protest 1: a lesson for all. R.J. Thorn. The Canadian Architect (Archive: 1955-2005); Don Mills Vol. 19, Iss. 8, (Aug 1, 1974): 34-35.

Protest 2: a brain factory. James Acland. The Canadian Architect (Archive: 1955-2005); Don Mills Vol. 19, Iss. 8, (Aug 1, 1974): 36-39.

Critiques: no room for change. L.S. Langmead. The Canadian Architect (Archive: 1955-2005); Don Mills Vol. 19, Iss. 8, (Aug 1, 1974): 40-42.