Leora Bromberg

MI & MMSt Candidate

Graduate Intern, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Around this time last year, I was looking back on a semester in which I developed some new research interests in Judaica materials, from exploring Hebrew letterforms at the Massey College Bibliography and Print Room to becoming totally captivated by the story of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, MA. To top it all off, in the final lecture of book history class, I had a bit of an emotional experience when I handled, for the first time, a facsimile copy of the famous Sarajevo Haggadah—which sparked an idea for a bit of a rare book Passover experiment.

From the Hebrew root “HGD” (to tell), a Haggadah is the text at the heart of the Passover Seder (ritual feast) which recounts the story of exodus from slavery in Egypt that Jews are commanded to tell their children. The Sarajevo Haggadah, transcribed and illuminated in northern Spain in the mid-14th century, first gained public attention in the late 19th century when a Jewish family in Sarajevo by the name of Kohen offered it for sale to the Bosnian National Museum. Considered a rare masterpiece of medieval illumination and Hebrew script, the Sarajevo Haggadah is the most celebrated Passover Haggadah in the world. The manuscript is also protected under the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The Fisher Library collection includes two facsimile copies of this famous Haggadah (the catalogue records to those can be found here and here).

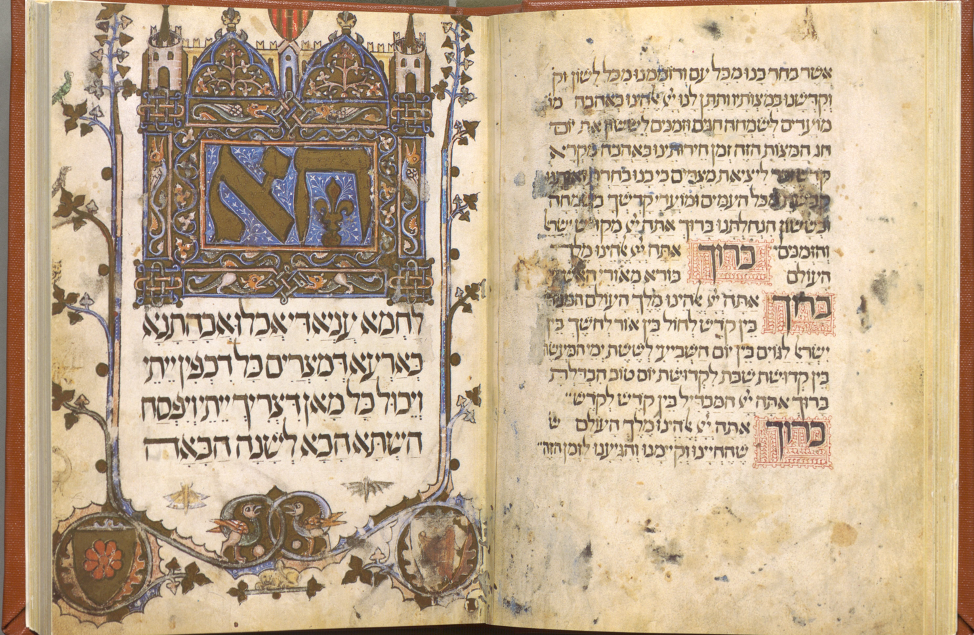

This manuscript offers a glimpse into medieval Jewish life. It is especially striking for its colourful illuminations of biblical and Passover ritual scenes and its beautifully hand-scribed Sephardic letterforms. As precious as this Haggadah was, and still is, Haggadot (plural) are books that are meant to be used in festive and messy settings—sharing the table with food, wine, family and guests. The Sarajevo Haggadah was no exception to this; its pages show evidence that it was well used, with doodles, food and red wine stains marking its pages.

Illuminated pages from the Robarts Library facsimile copy of the Sarajevo Haggadah.

The Haggadah is also remarkable for its story of survival over centuries of persecution. Scholars believe that the treasured book left Spain when the Jews were expelled during the Spanish Inquisition. A notation at the back of the book traces its journey to Italy in 1609, when it received a signature of approval from a Catholic inquisitor, ultimately protecting it from being burned. In 1894, the Haggadah was sold by the Kohen family to the National Museum in Sarajevo. Yet, even in the museum’s collection, many more threats still awaited this precious manuscript. In 1942, when the notorious Nazi commander Johann Fortner arrived at the museum to seize the Haggadah, the Muslim Chief Librarian of the museum, Derviš Korkut, risked his life to save it. With the codex tucked carefully under the waistband of Korkut’s trousers, he and the director of the museum lied to the Nazi officer, claiming the book had already been confiscated. From there, Korkut took the Haggadah to a small mosque located in a remote village, where it survived the war hidden among Islamic texts. Back in the museum, the Haggadah was saved once again from warfare in 1992 during the Bosnian War, when another Muslim librarian risked his life to retrieve the manuscript and secure it in a bank vault. Curiously, this book that carries the story of slavery and exodus itself experienced a long journey of survival. Some have interpreted the Sarajevo Haggadah as a symbol of coexistence, given how its story involves so many different cultures, touching Jews, Christians and Muslims alike, and individuals who helped to protect it.

Back in our final book history lecture, my classmates and I were sharing reflections on our reading of Geraldine Brooks’ People of the Book, a novel that follows the journey of the Sarajevo Haggadah, imagining fictional stories behind its many mysteries along the way. As we discussed the novel, we also circulated the Robarts Library facsimile copy of the Sarajevo Haggadah. When the facsimile landed in front of me, I flipped through it and tuned out of the discussion. Though I only have a working knowledge of Hebrew and am by no means fluent, I was excited by my ability to clearly read the Hebrew on the manuscript pages before me. Whether or not you are able to speak or read the language, the story and songs in the Haggadah become familiar, just based on the centrality of the text to the holiday and its repetition for two nights in a row, year after year. This story is meant to become ingrained, as, on Passover, it is said that every Jew should regard themselves as if they had personally gone forth from Egypt. I was shocked that even with my limited knowledge of Hebrew I could hold a copy of this very old and mysterious book and actually read it. At that moment, I felt as though I had a very different relationship to this book than my classmates. After all, an English manuscript produced around the same period would be fairly incomprehensive or even illegible to the modern, untrained eye. I raised my hand and shared this feeling with the class, pointing out that I was able to read the words avadim hayinu, “we were slaves”… This sparked an idea: What would it be like to bring the copy of this medieval manuscript home with me to read at my family’s Passover Seder? The use of facsimile reprints of this or other manuscript Haggadot at the Passover Seder is not uncommon. This is a holiday where rare books may really come into play.

The Robarts Library facsimile copy of the Sarajevo Haggadah. The illuminated word on the bottom left begins “avadim hayinu…”

Since I usually need to rely on English translations in modern Haggadot in order to follow along during the Seder, on the first night of Passover, I set my place at the table next to my mother, knowing that she could help me decipher the medieval script if I lost my place (which I inevitably did). In the end, it became a team effort, where my mother and I laid the facsimile between us, taking care to protect the book from the table. We pointed out curiosities along the way, including any variations in the text or letterforms we could spot, delightful illustrations of small dragon-like creatures that perched on top of colourful and gilded letters, and wine stains and other markings. We were excited to see that the text was fairly accurate to the contemporary ritual. Page after page, the Sarajevo Haggadah still rang true to the order of the Seder. This, of course, is to be expected, considering that Seder actually means “order.” The family that originally commissioned this manuscript may have sung the songs to different tunes, followed slightly different customs and feasted on a different spread of festive dishes. Yet, all these centuries later, their Passover Haggadah remains legible and true to our current practices.

Wednesday marks the first night of Passover. This year, with social distancing in place, we will, unfortunately, be unable to host traditional large gatherings. Now, more than ever is the perfect time to take advantage of the Fisher Library’s digital collections. Why not try a rare book Passover experiment of your own? The Fisher Library has a large collection of Haggadot, many of which have been digitized and made available online, including this siddur manuscript, and much of the Druck Collection of Kibbutz and Secular Haggadot (there are hundreds to choose from!). Bringing a rare Haggadah to your Seder table not only adds an extra layer of meaning to the experience, but it might also offer a window into decades or even centuries of Jewish tradition.