The Classics Department Papyrus Collection held on long-term deposit at the Thomas Fisher Li-brary has a stunning array of decorated papyri from the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE) of Ancient Egypt that were used for cartonnage. A process by which layers of linen or papyrus were covered with plaster and adorned with gold and vibrant pigments, cartonnage was easily produced and an inexpensive means of demonstrating status. This status would be replicated in the Afterlife, carton-nage being used primarily for funerary masks and coffins. Apotropaic symbols and phrases were employed to protect and embellish the mummified body in burial as the deceased began their jour-ney through the Underworld. The iconography and coloration of cartonnage was used both to rep-resent the natural environment and to convey complex religious concepts. The imagery employed constantly evolved between periods and owners and included a variety of divine and royal symbols, geometric and floral designs, and hieroglyphic inscriptions—though there is some standardization with respect to which designs and figures were placed over specific sections of the body.

During the Ptolemaic Period separate cartonnage panels were used to cover parts of the mummy, specifically the chest, torso, and legs. The face had a cartonnage mummy mask and the feet had a cartonnage boot—though there are some cases where it is just a panel. The mask consisted of a gilded or non-gilded face and a tripartite wig that was blue or stripped with blue pigment. This re-flected divine association since the hair of deities was said to be blue. Geometric designs were placed along the neck and towards the end of the wig to replicate beading, and nominally floral de-signs were placed atop the wig to evoke rebirth and rejuvenation, drawing on the lotus’ cyclical na-ture of blossoming at sunrise and closing as sunset.

Cartonnage atop the chest always replicated the usekh-collar, a broad collar consisting of horizontal rows of colourful beads and amulets made of precious and semi-precious stones. While primarily a marker of status worn by royalty, the elite, and even the divine, some Egyptologists believe the col-lar contains mythological connotations because, when placed upside-down, the semi-circular hori-zontal rows seemingly evoke the primeval mound of creation, with colourful rays emanating from it. It thus symbolizes creation and rebirth, especially since when looked at upside-down the head can be seen as emerging from the collar—just as the creator god Atum emerged from the primeval mound. As a material object the usekh-collar is often shown with falcon-head terminals which sym-bolize the god Horus and his apotropaic nature. This is reproduced in one of the fragments held at the Fisher: a falcon head is placed atop the collar and crowned by a sun-disc, in this case symboliz-ing the syncretization of Horus and the sun god Re into Re-Harakhty—the sun god in his most powerful state.

Sometimes cartonnage covering of the torso/abdomen is combined with the chest or legs, and at other times it is a panel on its own. Nominally the iconography depicts winged divine beings such as a beetle representing Khepri, the god of the morning sun, or a kneeling goddess crowned with a sun-disc seen below, which can represent Isis or the sky goddess Nut as seen in the image below. By the Ptolemaic Period iconographic features were shared between goddesses since attributes were conflated. Isis always possessed avian iconography, but by the New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BCE) she appropriated Hathoric imagery as she assumed many of the goddess Hathor’s mythic roles—acquiring solar connotations. The association of wings with Isis can symbolize her resurrective powers, as her wings revived her deceased brother-consort Osiris, or her apotropaic powers as mother goddess and one “great of magic.” Nut always possessed celestial iconography, including solar imagery, but avian and Hathoric features did not appear until the New Kingdom. The associa-tion of wings with Nut symbolizes her protection of the deceased—ascribing her a maternal na-ture—as she embraced the dead for all eternity in her womb, the coffin, just as she did the sun god during his nightly journey.

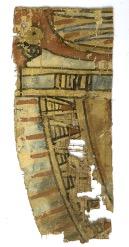

Leg panels can feature a variety of funerary iconography, such as the process of mummification or mummiform imagery as noted in the left image below, contain hieroglyphic inscriptions of funerary spells as noted in the right image below, depict divine figures and symbols, and be rich in geomet-ric designs. Cartonnage placed upon the legs nominally contains a central divisional line—sometimes filled with hieroglyphs—with symmetrical iconography on each side. The boot or panel covering the feet likewise had the same divisional line and symmetrical imagery—a characteristic feature of Ancient Egyptian coffins and other funerary equipment since the Middle Kingdom (c.2055–1650 BCE). The most common iconography found atop the feet are depictions of feet sur-rounded by floral and geometric designs, or a reclined jackal atop a shrine which symbolizes the embalmer god Anubis, protector of burials and guide of the deceased on their journey through the Underworld.

- Chana Algarvio, TALint Student, Fisher Library